A scene from the Leben der heiligen Altväter (1482)

Wesley’s Christian Library Vol 1

Volume 1 Contents

- Preface

- Apostolical Fathers

- Macarius

- Homilies

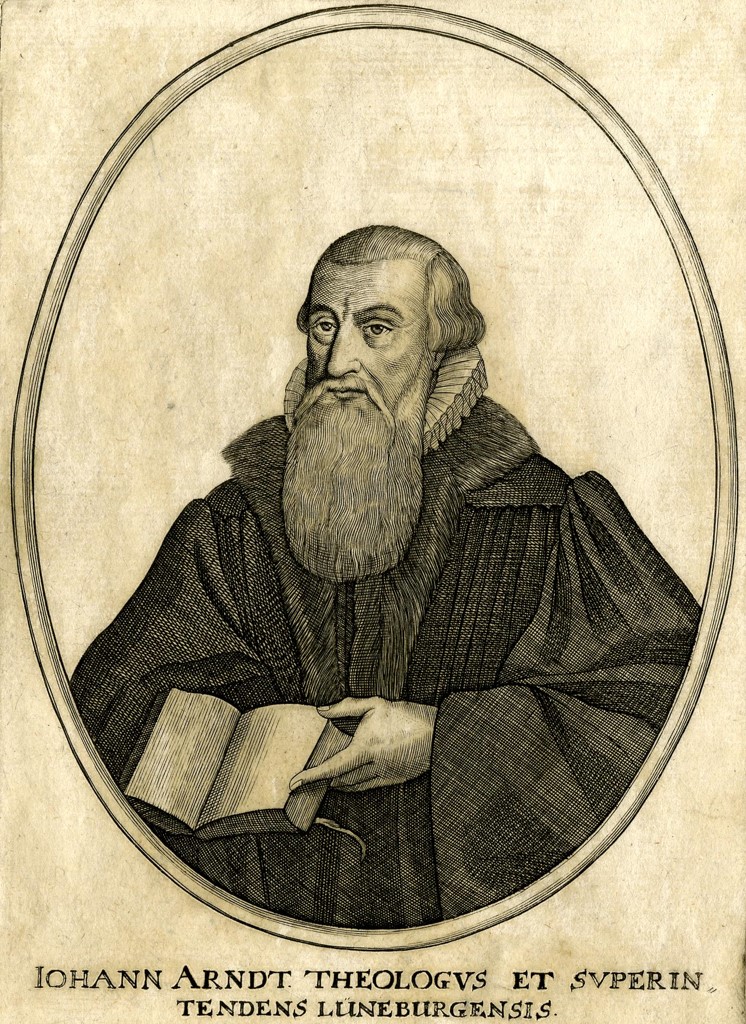

- John Arndt

- True Christianity

Description & Discussion

Preface: Wesley’s seven-page Preface in volume 1, dated March 25, 1749, is obviously intended to be programmatic for the whole series. In fact it is a bad fit for volume 1. Wesley’s boast that in no other language or country is there “a more complete body of Practical Divinity than is now extant in the English tongue, in the writings of the last and the present century” envisions the later volumes filled with Anglican and Puritan spiritual writing. But it hardly describes this first volume, which is all older works in translation: second-century Greek Fathers, the fourth-century Macarius of Egypt, and German Pietist Johann Arndt’s Wahres Christentum (ca 1610, Arndt’s book does meet the recency requirement). Further analysis of the Preface, then, belongs mostly in an overall discussion of A Christian Library. As for Volume 1 itself, the Preface alerts us to consider its idiosyncratic selection of materials in light of the larger project.

Epistles of the Apostolical Fathers: In 1749, what counted as “apostolic fathers” was a bit different. The name itself had only come into use in 1680s, Didache not published until 1880s, etc.

Selection: Clement to the Corinthians, Polycarp to Phillipians, seven letters of Ignatius of Antioch (Ephesians Magnesians Trallians Romans Philadelphians Smyrneans Polycarp), and the martyrdoms of Ignatius and Polycarp.

There is a general intro “to the reader” and individual introductions.

Q: Whose translation and notes are these? I predict this Q has already been studied by Wesleyans studying his use of the church fathers. Plug that stuff in here.

Macarius: In his 1765 sermon “The Scripture Way of Salvation,” Wesley exclaimed: “How exactly did Macarius, fourteen hundred years ago, describe the present experience of the children of God!” And 31 years before preaching that sermonr, Wesley had recorded in his diary that he “read Macarius and sang” at sea on July 30, 1736 (see his Diary for that day; also Outler, John Wesley, p 9). An important enough figure in his own right, Macarius of Egypt (ca. 300 – 391) loomed as an outsized and symbolic patristic presence in John Wesley’s Christian imagination. Wesley’s devotion to Macarius’ Homilies can be traced to the appearance of an English translation of them in 1721, under a title that must have been pure electricity to an eighteen-year-old John Wesley: Primitive Morality: or, The Spiritual Homilies of St. Macarius the Egyptian; Full of Very Profitable Instructions Concerning that Perfection, Which is Expected from Christians, and Which it is Their Duty to Endeavour After. The translation was the work of Thomas Haywood (1678-1746), though he was only identified as “a Presbyter of the Church of England” on the title page. There are several good discussions of Wesley’s reception of Macarius; a recent one that is free is Maria Fallica’s “An Anglo-Syrian Monk: John Wesley’s Reception of Pseudo-Macarius,” Open Theology 2021; 7: 491–500. See also:

John C. English, “The Path to Perfection in Pseudo-Macarius and John Wesley.” Pacifica 11 (1998), 54–62; Coleman M. Ford, “‘A Pure Dwelling Place for the Holy Spirit’: John Wesley’s Reception of the Homilies of Macarius.” The Expository Times 130:4 (2019), 157–66; David C. Ford, “Saint Makarios of Egypt and John Wesley: Variations on the Theme of Sanctification.” Greek Orthodox Theological Review 33:3 (1988), 285–312; Mark T. Kurowski, “The First Step Toward Grace: John Wesley’s Use of the Spiritual Homilies of Macarius the Great.” Methodist History 36 (1998), 113–24; Hoo J. Lee, “Experiencing the Spirit in Wesley and Macarius.” In Rethinking Wesley’s Theology for Contemporary Methodism, edited by Randy L. Maddox and Theodore Runyon, Nashville: Kingswood, 1998; Ki Jung Nam, John Wesley’s Editing of Pseudo-Macarius’s Spiritual Homilies: A Redactional Study Focusing on the Theme of the Spiritual Senses, Ph.D. thesis, Berkeley, California, 2018; Howard A. Snyder, “John Wesley and Macarius the Egyptian.” The Asbury Theological Journal 45 (1990), 55–60; David R. Walls, The Influence of the Greek Fathers’ Doctrine of Theosis on John Wesley’s Doctrine of Perfection, Ph.D. thesis. The University of St. Michael’s College, 2015.

For Wesley, Macarius was the ideal witness to the primitive Christian teaching of spiritual perfection. Also, for Wesley, “Macarius” simply means these homilies. For the complexities of identifying the Macarian corpus and its author(s), see the standard works like Marcus Plested’s The Macarian Legacy: The Place of Macarius-Symeon in the Eastern Christian Tradition (Oxford University Press, 2004).

Macarius’ Fifty Homilies can be found in Migne’s Patrologia Graeca vol 34. The Migne text incorporates text-critical improvements made by H.J. Floss in 1850 (Cologne). Haywood in 1721 was working from a text published by J.G. Pritius (Leipzig, 1699) and his own consultation with an Oxford manuscript he describes in his introduction. Because of its 1749 date, Wesley’s Macarius does not always map onto modern editions precisely. A more modern translation, Fifty Spiritual Homilies of St. Macarius the Egyptian, A.J. Mason (SPCK 1921), is more legible, and Mason deliberately renders key phrases into idiomatic English and without close adherence to Greek precision.

Wesley’s three-page introduction, “Of Macarius” (1:69-71), is a pastiche of phrasing gathered from Haywood’s 92-page Introduction.

Specter of Messalianism (define). If you think of Macarius as aligned with the Messalian heresy –and that’s a big if– then retrieving and highlighting his homilies could be a subversive gambit for identifying a genealogy of a certain radical teaching on holiness. Reading Wesley with suspicion, we might take volume 1 to be setting up the story of a persecuted minority witness in church history (Macarian perfectionism), followed by two and a half volumes tracing the bloody trail of martyrdom, and issuing in the Puritans (considered precisely as a radical voice marginalized by the Church of England). This is not how I read Wesley, but the possibility deserves some critical scrutiny.

Johann Arndt’s True Christianity: This is Boehm’s translation of a 1605-1610 book, complete with his letter to the Queen –a letter that sounds rather Wesleyan itself. Arndt (here called John Arndt) is a crucial figure in continental Pietism, and True Christianity is the key text. This selection stands in for much German influence on Wesley (he will not include Zinzendorf or any Moravian authors in later volumes). Its inclusion may have, for Wesley, a kind of symbolic value in the structure of the volume: Methodism is the same as Pietism which is the same as Macarian spirituality which is the same as primitive Christianity.

Fred Sanders

Fred Sanders