A scene from the Leben der heiligen Altväter (1482)

The Eternal Love of Godfrom Thaddeus Williams' Revering God

Thaddeus J. Williams, Revering God: How to Marvel at Your Maker (Zondervan Academic, 2024), 120-122.

My Biola colleague Thaddeus Williams invited me to write a short, personal account of how the truth of the Trinity had affected my life. The brief report (less than a thousand words) was one of a half dozen testimonies that Thad incorporated into his book Revering God: How to Marvel at Your Maker (Zondervan, 2024). I tried to write it in a way that contributed to his book’s overall goal and tone. Revering God is definitely a theology book, but it’s divided into thirty chapters of reasonable size and deliberate focus, precisely so readers can move through it in a month. That means it’s outfitted to work as a devotional book, to accompany readers through a thirty-day experience of pondering God and being changed by the truth. To that end, here’s part of my testimony about the Trinity:

In the year that I became a Christian, I was a teenager with what I suppose must be a pretty predictable set of problems. I was fearful about an uncertain future, deeply lonely and unconvinced I was lovable, embarrassed about my obvious shortcomings, and so on. I guess a lot of young people have some version of these feelings: a little bored, a little scared, a little ashamed. As I started going to church and reading the Bible, I gradually began to understand things better. Underneath my felt needs I began to recognize my real needs: reconciliation with God, forgiveness of sin, and power to live for Christ. God met me where I was and took me somewhere better than I knew. The things I didn’t even know were problems (my refusal to give glory to God) were solved in a way that also happened to solve many of the things I did know were problems (insomnia, defensiveness, risky behavior).

Something similar happened in my understanding of who God is, and this is where the theology really starts to kick in. Because God had moved into my life and solved my spiritual problems at their root, I recognized just how much I benefitted from his grace. In a lot of ways, I began to relate to God as my problem solver, my provider, my teacher. In one sense, this was fine: we finite and fallen creatures are always needy, never self-sufficient. So of course God gets our attention and attracts our gratitude as the one who meets our needs. But after a few months of rejoicing in God’s wonderful availability to me, and of growing in prayer and Bible study, I noticed that something was wrong. Somehow it was still just me at the center of the whole project, and God was orbiting my needs like some gracious satellite. That couldn’t be right. As I read and re-read the Bible, it became clear to me that I needed to be decentralized from my own life story and situation. God had to be the center.

I kept some notes back then, and one heading under which I started writing down relevant Bible passages was “Notes for a Gospel Outside of Me.” What I meant by that, though I was groping in the dark and barely had words for it at the time, was that I knew I needed God to be central. My relation to God needed to become theocentric rather than me-centric. And if that was going to happen, I would have to recognize that God’s own divine life had a lot going on in it, up above my head, without reference to me in the first place. Of course I wanted God to have something to do with me eventually, but what I was dying to find was a way of grasping how God’s own eternal life and liveliness was independent of me.

Every time I found a passage (whether in the Bible or in a devotional book, including things by C.S. Lewis and J.I. Packer) that suggested the depth and independence of the life of God, I would write it down in a notebook under that heading, “Gospel Outside Me.” Gradually I accumulated several pages of these passages. Slowly I noticed that the richest expressions of them had a few things in common. They tended to name the Father and the Son: “Father, glorify me in your presence with the glory I had with you before the world began (John 17:5 NIV).” Sometimes they also named the Holy Spirit: “[Jesus] rejoiced in the Holy Spirit and said, ‘I thank you, Father [Luke 10:21].” “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased [ Matt 3:17].” The bigness of this conception of God began to dawn on me. The greatness of what existed between the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit began to outflank my own intellectual horizon.

And then something happened. I read a really bad Christian book that a friend recommended. I forget the name of it now, or its author, but I remember that it was relentless in its message that God’s love for me was at the center of the universe. It was very straightforward in saying it: there was nothing deeper than God’s love for me, for me, for me. This forgettable book was a catalyst for me; it was the lie that made me perceive the truth. God’s love for me was not the central thing. God’s love in itself was the one great thing, and it had its own secure foundation, without which there would be no love for me to be invited into or rescued by. Furthermore, those notes I was taking about how the Father loved the Son in the Holy Spirit – they were the concrete details I had been needing in order to understand God’s absolute, sovereign self-sufficiency. The Trinity met my need for a God whose life was about more than just meeting my needs. This was the foundation for a gospel that certainly reached down and saved me, but that was securely anchored in something about as far outside of me as it was possible to get.

In the decades since then, I’ve learned a lot more about the triune God. I’ve written several books and articles about the doctrine, and I never get tired of teaching about it in churches and even in academic settings. The love of the Father and the Son in the unity of the Holy Spirit continues to be my lifeline and my anchor, and the more I study it the more certain I am that this gospel that made all the difference for me has its source in a vast, profound reality that is way outside of me, but draws me in closer and closer.

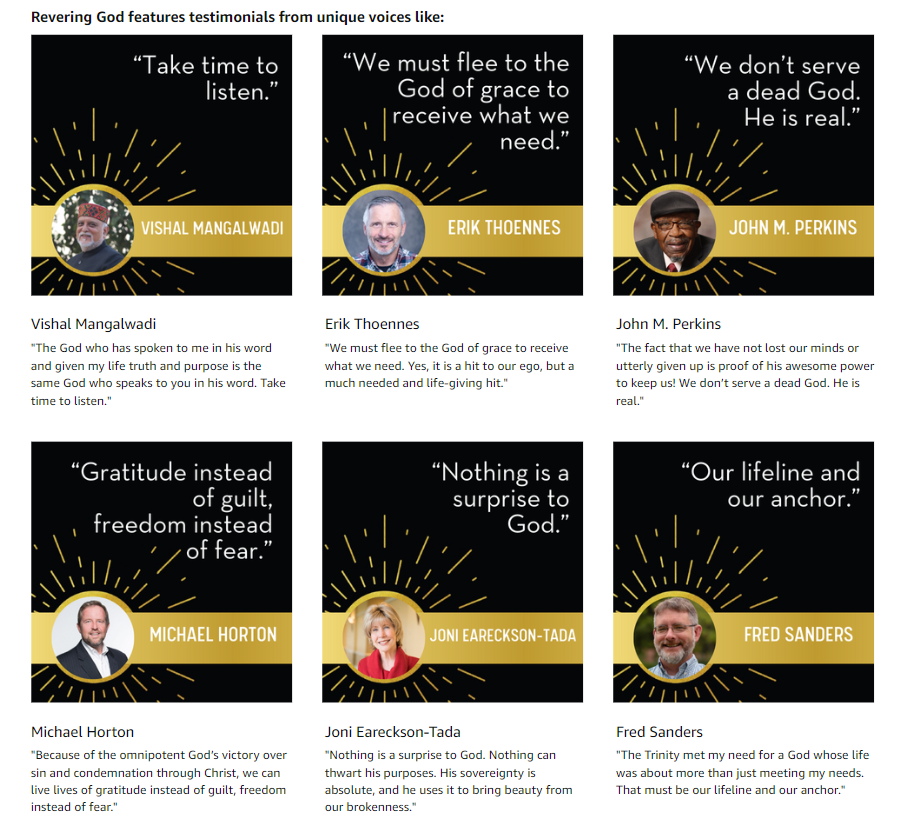

The other five “personal voices” in Revering God are those of Joni Eareckson-Tada, Michael Horton, John Perkins, Erik Thoennes, and Vishal Mangalwadi; you can see pull quotes and other tantalizing details at the book’s Amazon page:

Fred Sanders

Fred Sanders