A scene from the Leben der heiligen Altväter (1482)

Wesley’s Christian Library Vol 4

Vol 4 Contents

Clark’s Supplement to Fox’s Acts and Monuments of The Christian Martyrs Part I

- A Narrative of The Bloody Cruelties,

- A Narrative of The War in The Valleys of Piedmont,

- A Relation of The Distressed State of The Protestants

- The Persecution of The Church of God in Poland

- The Persecution by The Duke De Alva, In the Netherlands

- The Persecution of The Church of God in Ireland

- The Persecution of The Church of God in Scotland

Bishop Hall:

- Meditations and Vows Divine and Moral

- Heaven Upon Earth; Or, Of True Peace of Mind

- Holy Observations

- Solomon’s Song Paraphrased

- Letters on Several Occasions:

- To My Lady Mary Denny

- To My Lord Denny

- To Sir Fulk Greville

- A Passion Sermon

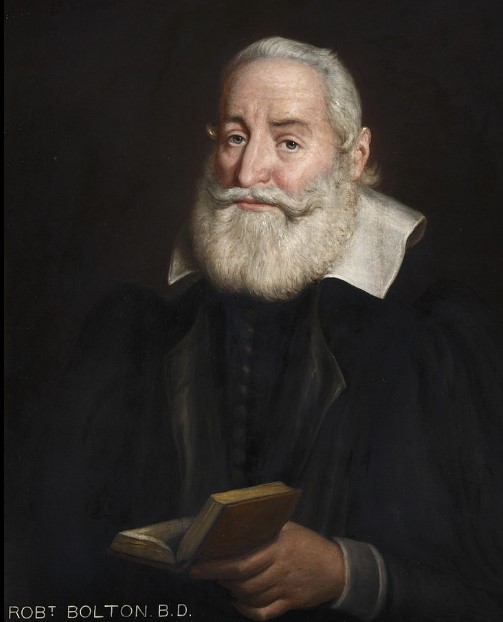

Robert Bolton:

- The Life and Death of Mr. Bolton

- A Discourse of True Happiness

- General Directions for A Comfortable Walking With God

Description & Discussion

Clark’s Supplements: Did Wesley supplement the supplement? Somewhere he complains about what’s missing. Wesley seems to have been guided editorially by the need to draw a line from the primitive church to his own time, and for whatever reason he chose martyrology as the link.

Preface: Here in volume 4, the 1819 editors have made a confusing error. Page 103 is the title page for Bishop Hall’s Meditations, but then it is followed at page 105 by a four-page Preface in which Wesley offers his reasons for including so many Puritan authors. This is out of place: Indeed, we can see that the corresponding Volume 7 of the 1749 edition has it right:

In fact, though it is less conspicuous in the 1819 edition, Wesley has inserted here (at what was the first page of 1749’s Volume 7) a hinge point of the whole series. Having traced church history from the second century to modern England in volumes 1 through 6, Wesley’s Christian Library now finally takes up its main, stated task: presenting the choicest pieces of practical divinity produced in the English tongue. He marks the transition explicitly in the Preface:

After an account of the lives, sufferings, and deaths of those holy men, who sealed the ancient religion with their blood, I believed nothing would either be more agreeable or more profitable to the serious reader, than some extracts from the writings of those who sprung up, as it were, out of their ashes. These breathe the same spirit, and were, in a lower degree, partakers of the same sufferings. Many of them took joyfully the spoiling of their goods, and all had their names cast out as evil; being branded with the nickname of Puritans, and thereby made a bye-word and a proverb of reproach. (4:105, with emphasis added)

Consider how much church history Wesley has elided by this move: the church of the ecumenical councils, the Scholastics, and the Reformers is relegated to the background of the succession of martyrs. Apparently for the purpose of English practical divinity, the two pillars of the bridge are primitive Christianity on the far side and Puritanism on the near side. The bridgeway itself is martyrs.

Wesley proceeds to a highly illuminating account of the many strengths and the few admitted weaknesses of the Puritan authors. He has “endeavoured to rescue from obscurity a few of the most eminent” of the Puritans (4:105). He limits this rescue work to “a few” authors (“for there is a multitude”), and even of these few authors he only offers abridgements of a select few works, since “some of them are immensely voluminous. The Works of Dr. Goodwin alone would have sufficed to fill fifty volumes.” (4:105) It would be interesting to quantify the availability and influence of authors like Goodwin and Owen in the early 1700s, in order to grasp whether Wesley’s Library contributed to their influence or helped to “rescue from obscurity” their works. As for what contribution the Puritans make to Wesley’s own voluminous pastoral project, he is clear: “I have therefore selected what I conceived would be of most general use, and most proper to form a complete body of Practical Divinity.” (4:105)

The Preface in the middle of Volume 4 (that is, at the opening of Wesley’s 1749 Volume 7) rehearses the stylistic liabilities of the Puritans:

- Language not so smooth and terse as that of the present age.

- Many expressions now quite out of date; some unintelligible to common readers.

- Some too stiff, laboured, and affected.

- Others, though, use language too low, and purposely neglected.

- Exceeding verbose, full of circumlocutions and repetitions. (4:106)

These Wesley promises to have mended:

But I persuade myself, most of these defects are removed in the following sheets. The most exceptionable phrases are laid aside; the obsolete and unintelligible expressions altered; abundance of superfluous words are retrenched ; the immeasurably-long sentences shortened; many tedious circumlocutions are dropped, and many needless repetitions omitted. (4:106)

The Puritan writers have two “other blemishes:” They “drag in controversy on every occasion” and “they generally give a low and imperfect view of sanctification or holiness.” (4:106). As for the first, Wesley simply omits their controversies. As for the second, Wesley believes he has deployed the Puritan texts in A Christian Library in such a way that they are surrounded by and supported by other authors with more perfect views of holiness.

When Wesley turns from their weaknesses to their strengths, his praise of the Puritan writers is positively effusive:

- They appear quite possessed with the greatness and importance of their subject.

- They are thoroughly in earnest. (4:106)

- They write as if they either just returned from, or are launching into, eternity.

- Their judgement is generally deep and strong.

- Their sentiments are generally just and clear.

- Their tracts are full and comprehensive, exhausting the subjects.

- They exalt Christ, setting him forth in all his offices.

- They sum up all things in Christ, deduce all things from him, refer all things to him.

- Next to God himself, they honor his Word.

- They are mighty in the Scriptures, equal to any who went before them.

- They are continually tearing up the very roots of Antinomianism.

- They show the absolute necessity of the evangelical repentance that follows faith.

- The peculiar excellency of these writers is their building us up in faith. (4:107)

- They lead us by the hand from conversion to growth in grace, from strength to strength. (4:108)

This is hardly a grudging commendation! I have argued elsewhere that we should understand Wesley as a perpetuator of Puritan piety; for an extended argument that also attends to the Puritan presence in A Christian Library, see Robert C. Monk, John Wesley: His Puritan Heritage, 2nd ed. (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 1999), 247-254. Monk includes some statistical analysis.

Bishop Hall: The first Puritan Wesley introduces is probably not a Puritan: Joseph Hall (1574-1656). Wesley lists him along with them in the Preface but then demurs: “if we rank him in that number.” (4:106) Joseph Hall was

See this article 1966 at the churchman.

Hall was prolific (see PRDL and Luminarium, but Wesley chose six of his works to present in shortened form:

- Meditations and Vows Divine and Moral

- Heaven Upon Earth; or, Of True Peace of Mind

- Holy Observations

- Solomon’s Song Paraphrased

- Letters on Several Occasions:

- To My Lady Mary Denny

- To My Lord Denny

- To Sir Fulk Greville

- A Passion Sermon

What did he leave out? Including the first three are obvious choices; the final three less so. And where are the Contemplations? And where is Arte of Meditation?

Those who have never heard of Joseph Hall, or have never read him, should be grateful to Wesley for drawing attention to Hall by including him in A Christian Library. Take up and read! However, readers who already know and love the writings of Joseph Hall are likely to be sorely disappointed by how Wesley treats his texts. Some details for each text are below. But overall, John Wesley is simply not an editor well qualified to edit Joseph Hall. Hall was a profound scholar of antiquity, and wrote in a lofty, classicizing voice. His way of bringing Greek and Roman style into English composition marked a permanent contribution to the progress of English style. In histories of English literature, Hall is best remembered either for importing Juvenalian satire into our language, or for introducing a type of sententiously meditative mood characteristic of Seneca. The man who could accomplish such literary feats in the 1600s did not need his paragraphs edited down or his diction trimmed by a preacher in the 1700s. The two possible defenses of Wesley’s hubris in this case are that (1) he was consciously making Hall’s prose easier to read for a less educated audience who might not otherwise read Hall at all, and (2) he was updating words and spellings that had become out of date in the linguistically busy century since their first publication. (Since Wesley’s own writing is now quite similarly archaic to twenty-first century readers, the value of the second justification has evaporated.)

Hall, Meditations and Vows: The first of Wesley’s selections from Hall shows probably the roughest Wesleyan editing of a text carefully composed. Hall wrote and published these meditations in the ancient format called centuries: lists of thoughts numbered up to 100. Well-known Christian examples include Maximus’ Centuries on Theology and Traherne’s Centuries of Meditations. Hall wrote three centuries, meaning 300 numbered thoughts. Each century is dedicated to a different recipient, and in each case the themes of the hundred thoughts are subtly tailored to the “dramatis personae” of the dedicatees (perhaps these dedications indicate why they are not just Meditations, but Meditations and Vows. For a very faithful and attentive reproduction of Hall’s book, see Meditations and Vows, Divine and Moral by Joseph Hall, edited by Charles Sayle (E.P. Dutton, 1901).

None of these structural elements are preserved by Wesley. There are no hundreds and no dedications. Even the subtitle Divine and Moral, an important clue to Hall’s theology of nature and grace, is reduced to &c. What Wesley delivers is a series of numbered thoughts that run from 1 to 73, drawn from across the original 300. They are perhaps a collection of the most striking from among the 300, and they show the Bishop at his best, but in abbreviated form.

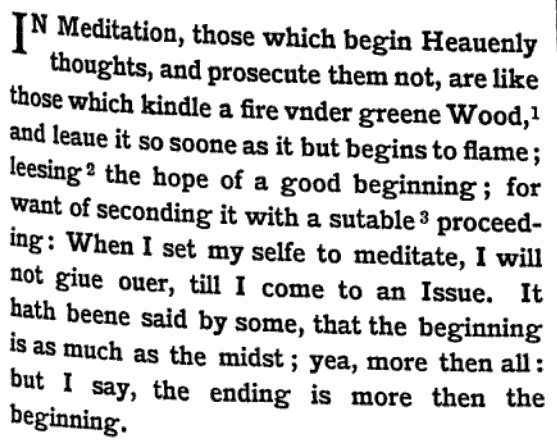

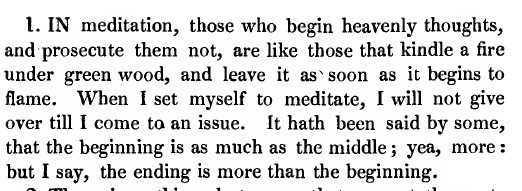

Furthermore, Wesley carries out various edits of the snip-here snip-there variety to most of the meditations. Here is a side-by-side comparison of Hall’s original meditation 1 (first from Sayle’s carefully faithful 1901 edition) and Wesley’s abridgement (4:109).

(Meditations published serially; first century stood alone once.)

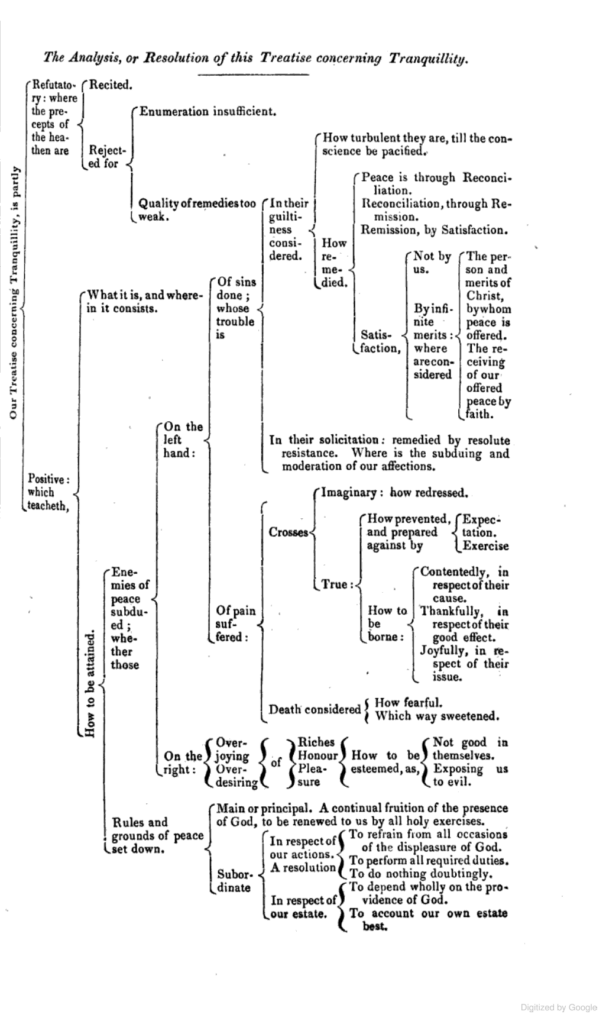

Hall, Heaven Upon Earth; or, Of True Peace of Mind: Originally published 1606 (GB copy here). Wesley’s sub-title “Of True Peace of Mind” replaces the original “Of True Peace, or Tranquility of Mind.” The work is sometimes referred to as “Hall on Tranquility.”

A real classic. The 1837 Works of Joseph Hall in 12 volumes puts Heaven Upon Earth at the beginning of volume 6, and provides a one-page dichotomizing chart of its arrangement. The schematic is rather shocking for readers who might not be expecting a piece of devotional writing to be so analytically careful.

Hall, Holy Observations: 88 of them; Wesley gives 24. See Hall Works vol 8.

Hall, Solomon’s Song Paraphrased:

Hall; Letters on Several Occasions: To My Lady Mary Denny, To My Lord Denny, To Sir Fulk Greville. These are found as decades in Works vol vi.

Hall, A Passion Sermon: See it here.

“The Church of Rome so fixes herselfe in her adoration upon the Crosse of Chrift as if she forgat his glorie. Many of us so conceive of him glorious that we neglect the meditation of his Crosse the way to his glorie and ours. If we would proceed aright we must passe from his Golgotha to the mount of Olives and from thence to heaven and there seeke and settle our rest.” xv-xvi

Robert Bolton: (1562-1631) Works at PRDL. Bolton is a great example of an author whose reputation was once very high but is now rarely read. Wesley includes a ten-page account of his life, and over 500 pages of his work (spread across volumes 4 & 5; in 1749 edition Bolton stretched from volumes 7 to 9).

Robert Monk’s book on Wesley’s Puritan Heritage includes considerable interaction with Bolton’s theology, with particular attention to his view of experiencing assurance of salvation.

Life and Death of Mr. Bolton: Source?

Bolton, A Discourse of True Happiness: here.

Bolton, General Directions for a Comfortable Walking with God: here.

Fred Sanders

Fred Sanders