A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

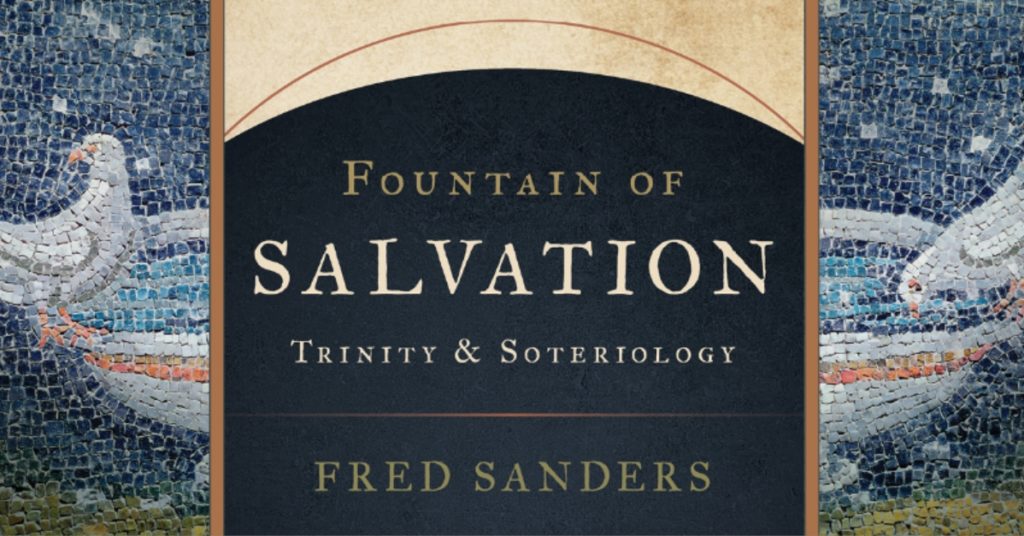

Cover Story: Birds at the Fountain

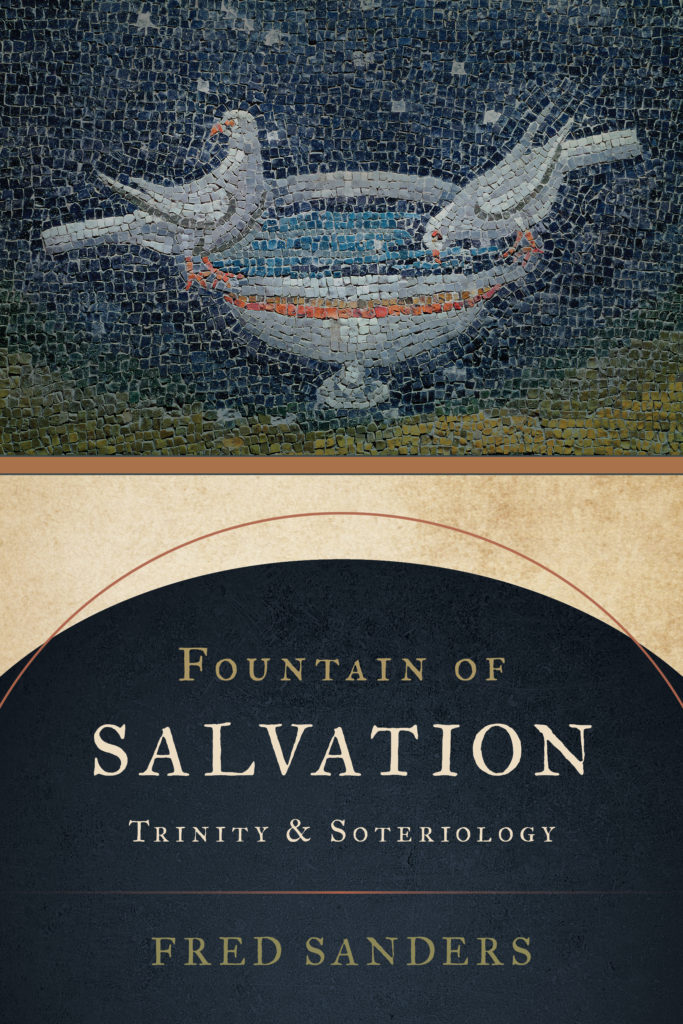

My book Fountain of Salvation: Trinity & Soteriology (Eerdmans, 2021) has a cover that is both beautiful and meaningful. It features a fifth-century mosaic of two birds drinking from a small fountain. The jewel-like mosaic tiles are in rich blues, whites, and greens, with a few orange accents. Part of the power inherent in the medium of mosaics is that each of the colored-glass tesserae, or tiles, catches light slightly differently from those around it. So the colors sparkle and change in response to the slightest movement on the part of the viewer, and no photo can ever quite do them justice.

But the photo used on this book is excellent, and is also excellently incorporated into the cover design. The designer (Meg Schmidt) noticed what not every viewer spots: that the fountain rests visually on the lower curve of a descending blue semicircle. She mirrored this shape in an ascending blue semicircle on the lower half of the book. The typography and other design elements nicely echo colors found in the mosaic, with green and pale orange/tan being especially well placed. It all comes together for a bright, clear cover that makes a viewer hope the book may also be full of good things.

“Fountain” is a focal image for the book’s big idea, which is that the triune God is the source of salvation; here’s how I put it in the in the introduction:

Salvation flows from its deep source in the triune God, who is the fountain of salvation. This phrase, fountain of salvation, goes back at least to a Latin hymn from the sixth century that praises God as fons salutis Trinitas. As one English translation renders the lines, “Blest Trinity, salvation’s spring, may every soul Thy praises sing.” The sense that the nature of salvation is only understood properly when it is traced back into its principle in the depth of God’s being is evoked by Scripture’s own way of speaking. The Old Testament bears witness to it in an intensely personal idiom, as for instance in Isaiah 12:2’s confident boast, “Behold, God is my salvation; I will trust, and will not be afraid; for the Lord God is my strength and my song, and he has become my salvation.” The connection here between God and salvation is direct: He is it. When Isaiah goes on to spell out an implication of salvation being in God, that is, that there is exuberant resourcefulness to be drawn from, then he uses our fontal image: “With joy you will draw water from the wells of salvation.”

I call a couple of witnesses to the trinitarian depth of this fountain imagery:

Scottish preacher Alexander MacLaren (1826–1910) points out that Isaiah is not referring to “the source of salvation as being a mere reservoir, still less as being a created or manufactured thing; but there lies in it the deep idea of a source from which the water wells up by its own inward energy.” That source, says MacLaren, is “GOD—GOD HIMSELF.” And the fountain of salvation from which we draw a continuous supply of water is presented “as having its origin in His deep nature, as having its process in His own finished work, and as being in its essence the communication of Himself.” Here the evangelical preacher truly warms to his subject, pointing out that if God is this way, in person the source of salvation, then we must expand the very idea of salvation correspondingly: “If there is a man or a woman that thinks of salvation as if it were merely a shutting up of some material hell, or the dodging round a corner so as to escape some external consequence of transgression, let him and her hear this: the possession of God is salvation, that and nothing else. … because its essence and heart is the communication of God Himself, and the bestowing upon us the participation in a divine nature, therefore the depth of the thought, God Himself is the well-fountain of salvation.”

There’s a bit more about that in the introduction, including some Hebrew exegetical insights (what’s the noun really mean, and why is it plural?) and wonderful trinitarian ponderings from John Gill.

At the very end of the intro, I offer one way of thinking about how the cover image relates to the book’s subject:

The image on the cover is a detail from a fifth-century mosaic in Ravenna, Italy. The cross-shaped building known as the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia is richly decorated inside with imagery of holiness and blessedness, including four sets of doves, like these, drinking from bowls of water. I chose this image for its inherent loveliness, its exquisite craftsmanship, its venerable antiquity, and its water imagery. I do recognize that what refreshes these little birds is more of a tiny tub than a great fountain, so I ask the viewer to use some sympathetic imagination. This is certainly not a book about a little bowl of blessing, but about God as salvation’s endless, triune source. However, visually representing the relation between the boundless depths of divinity and the experienced reality of salvation raises insuperable problems, not least of scale. If the little birds of Ravenna’s mosaics receive life and health and peace appropriate to their size, let this be our visual reminder that God supplies all our needs according to his riches in glory: not just from his riches, but in proportion to them.

Here is a little more about about the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia (which, as these things often turn out, is not really a mausoleum and does not contain the body of Galla Placidia). It’s the earliest of the remarkable set of buildings in Ravenna, Italy, which have survived in such excellent condition from the fifth and sixth centuries down to our time. Their mosaic decorations in particular are astonishingly well preserved and worth a pilgrimage to see. I got to visit these art historical marvels in 1998, and fondly hope to see them again someday. Here’s is a quick walk-through to show you where the cover birds are from.

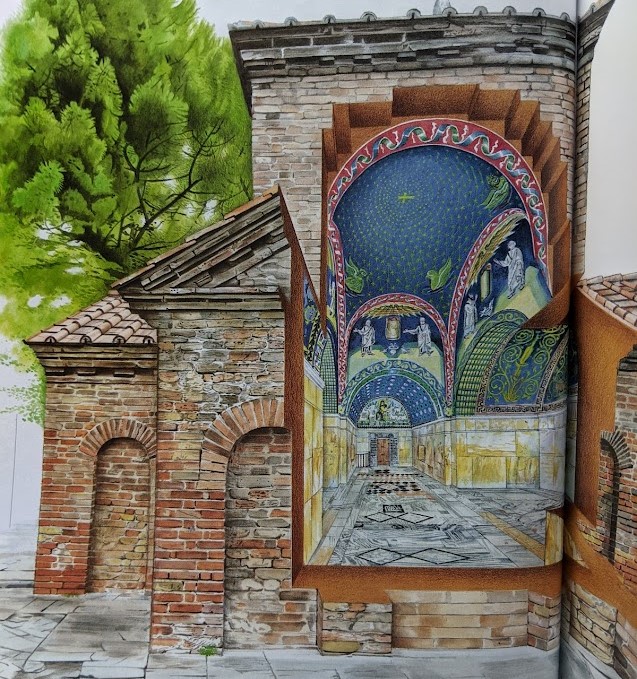

This is the Masoleum of Galla Placidia from the outside: a cross-shaped church structure with a squat, local-bricks look, Romanesque arches that go nowhere, and a tile roof.

But this cutaway view (from a tourist booklet I bought on site) shows you what’s waiting inside, and how it fits into the building’s structure.

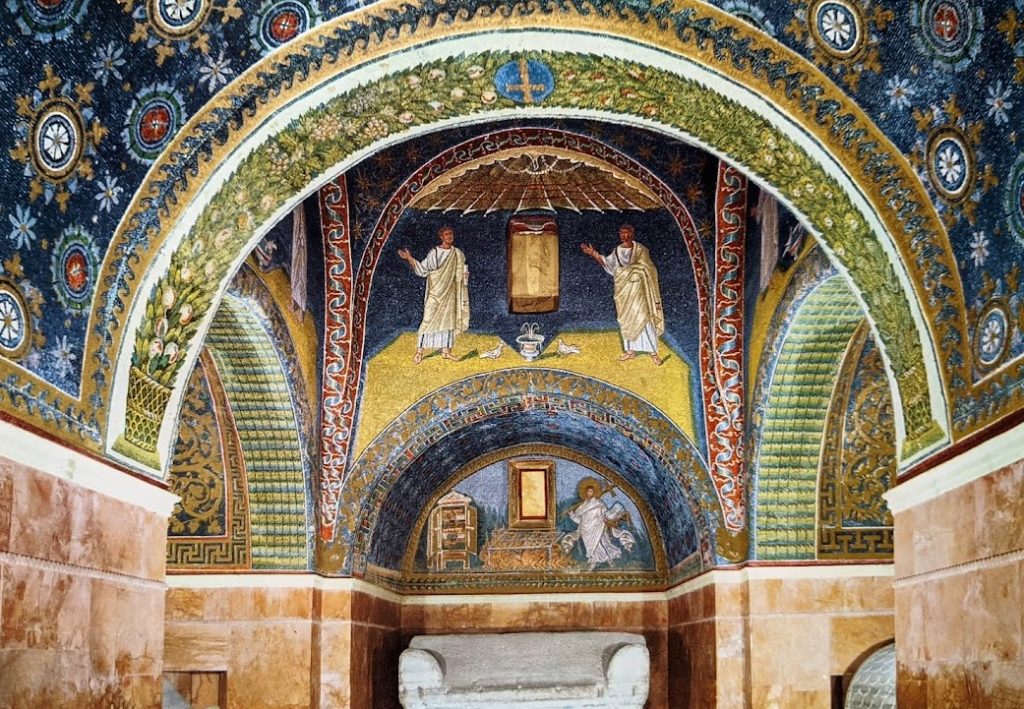

Like several of Ravenna’s World Heritage sites (the city has eight, in walking distance!), Galla Placidia is a jewel box of mosaic art. Here’s a wide view of the inside. I won’t describe the whole iconographic program, but it features deep blues and a lot of stars. People claim it has 570 mosaic stars overhead (then again, people claim it inspired Cole Porter to write “Night and Day,” so who knows). In the four higher lunettes are images of apostles, looking up and gesturing toward the dome just above them. Between each pair of apostles is an alabaster window, and (look closely) just below each of those four windows is a fountain-and-dove decoration:

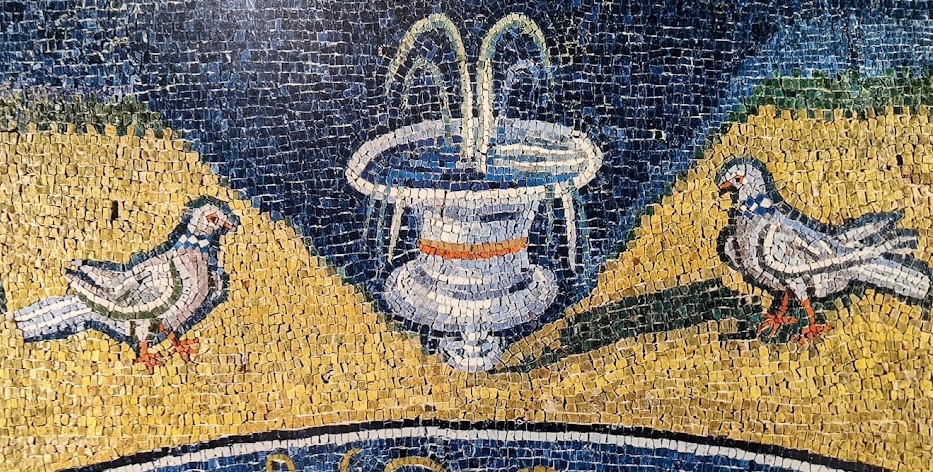

Here (below) is a closer look at one of those four lunettes, with a better view of the doves.

By the way, these two (who seem to be between Peter and Paul) are not the pair of birds on my book cover. They are very similar, but the droopy angle of the tailfeathers on the left dove is a giveaway. As I said, there are four sets, some very similar but some differing more (check out these two, who I’m guessing were by a later hand):

I mentioned above that mosaic tesserae catch the light differently, based on the exact angle at which they are pressed into the cement or glue that holds them to the wall. The result is that the white shades of the dove feathers take on an remarkable range of delicate coloration as you look at them; it can be a breathtaking visual effect in the dim light under the artificial canopy of stars. But in fact the doves are also actually made up of tesserae that the fifth-century artist chose to model shape and shade. In person, and from the ground floor, it’s simply impossible to be certain how many shades of white you are actually seeing, but in this close-up photo I think I can count six distinct colors carefully deployed here:

That’s a quick look at the birds on the book. There’s Bible, theology, iconography, and art history going on behind it all, but ultimately it’s translated into graphic design to help draw the eye to what’s inside the book. I suppose it took me more than a thousand words to suggest some of what’s going on in that picture, but that’s the kind of word-to-picture ratio you’d expect, isn’t it?

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.