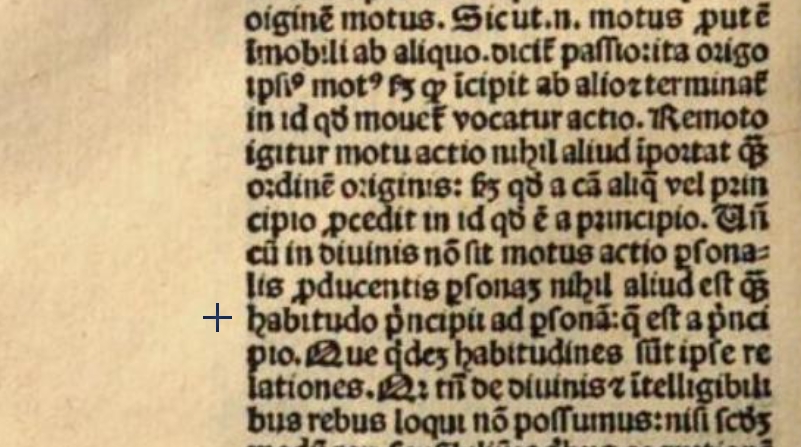

A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

No-Story Eternal Generation (Habitude)

One of the objections we sometimes hear to the doctrine of the eternal generation of the Son is that it seems like a story. To say that God the Father begat, begets, or has begotten God the Son sounds like saying “once upon a time, these events happened.” It’s a good objection, especially when both parties of the discussion agree in advance that we shouldn’t be telling any origin stories about how God came to be God. A God with a narrative of how he came to be God cannot be God.

There are several possible replies to the story objection. Before I suggest the one that I think is most effective, let me list four others. The first is to insist that this is exactly why we always put the adjective “eternal” in front of the noun “generation” when we talk about this doctrine. We have noticed the story problem, and have added the modifier “eternal” to intercept the misinterpretation. This is always the best short answer, but is not uniformly satisfying to all audiences.

The second is to spell out more carefully what is going on with the tensed verbs we have to use in describing the Son’s relation to the Father, and to admit that no tensed verbs are adequate. As Peter Lombard asked, should we say “the Son is forever generated” or “the Son was forever generated?” “Is forever being born” suggests incompletion, while “was forever born” suggests a rather inert point in past history from which the Son advances. (Sentences Book I, Distinction 9).

The third option is to provide some kind of model for how to picture this relation, which is what C.S. Lewis offered his popular audience in the broadcast talks that became Mere Christianity: Imagine a stack of two books, in which the top book sits there requiring the bottom book for its elevated location, but was somehow never in an unstacked position. The second book “arises from” the first, but never didn’t. Lewis combines this illustration with a high tolerance for mystery and a Boethian view of time and eternity.

The fourth option is to paraphrase the doctrine into philosophical categories that do not require taking time and tense into account; Mark Makin’s use of “essential dependence” terminology from the field of modern analytic metaphysics and epistemology is a good example of this (see his chapter in Retrieving Eternal Generation (Zondervan, 2017).

These are all fine, and perhaps you don’t want to go any further (or indeed even this far!).

But the most effective response I’ve seen is the one Thomas Aquinas develops (ST I, q. 41, a.1, ad. 2), building on Lombard’s work.

Aquinas says that when one thing originates from another, the main way we infer that to be true is to have seen it in action. If the cue ball imparts motion to the 8 ball, we infer that action originated from the cue ball and was the principle of passion, or reception, or the cause of motion, to the 8 ball. This is where we get the original sense of these words, Aquinas says.

But in a case where we use the same words to talk about a situation in which there is no motion, we still use the words while acknowledging the motionlessness. “If we take away movement, action implies nothing more than order of origin, in so far as action proceeds from some cause or principle to what is from that principle.”

Eternal generation, as a procession within God, is such a case. So we come to it with the words and concepts we derived from the land of time, but apply those words to eternity. The first thing we have to subtract, obviously, is the motion (or what I called “the story” above).

So Aquinas says that “since in God no movement exists, the personal action of the one producing a person is only the habitude of the principle to the person who is from the principle; which habitudes are the relations, or the notions.”

It’s worth lingering over that phrase, “the habitude of the principle to the person who is from the principle.” (habitudo principii ad personam quae est a principio) What is a habitude? In this context, it’s apparently something in a person that retains the status of that person being the principle of the other person. More concretely: the Father’s habitude is toward the Son who is from him.

If this still seems abstract (I know, I know), consider what a habitude isn’t: it’s not an action that takes up space or time. The Father doesn’t beget the Son at a particular time, nor does the Son proceed outward from the Father by local motion to some other place. But “nevertheless we cannot speak of divine and intelligible things except after the manner of sensible things, whence we derive our knowledge.” So go ahead, start with a begetting in time and space, and then abstract, or subtract out of it, the time and space. What you’re left with is what a begetting would be if it excluded time and space. And what is that? Well, it’s basically a relation. The Father-Son relation is the Father begetting the Son. Or you could say the Father begetting the Son, minus the concepts of time and space, is the Father-Son relation.

But there’s another thing habitude isn’t. It isn’t just a characteristic of a person, as it were simply inside them like an element that distinguished them from another person. It’s not as if the Father is gold and the Son is silver, so you can tell by their metallurgic properties who’s who. Instead, habitude includes the element of relatedness. If it were possible to inspect the Son’s habitude, that habitude inspection would reveal relation to the Father. So in that sense, the Son has a habitude that distinguishes him, but the habitude isn’t self-contained: it’s nothing but a reference to the Father. It’s like the aspect of the relation that is in him. It’s the habitude of Father-fromness.

Here’s one reason this is helpful. Let’s say you’re drawing three circles on the board to represent the persons of the Trinity. You’ve read the Athanasian creed, so you know to put the divine attributes in the space between them: divine power and wisdom and mercy all go in there: you don’t want to make three separate divine powers, or exclude any person from having the one divine power. But then you wonder what you should put in the person-circles. You draw arrows between them, showing that the Father begets the Son. But that’s between them, not in them. You write their names in them, but that’s just names. Nothing else? Surely something. John Calvin tried to solve this by simply insisting that each person had a distinguishing mark that showed them to be themselves and not another. But he refused to say more than that. I think what he intended by this distinguishing mark is something like habitude. Each person of the Trinity has within them the characteristic of being marked by their relation, or origin, or how they stand in the relations of origin, from the other.

Aquinas admits this, and introduces habitude when he’s describing the persons in terms of both their relations and their actions. Relations don’t imply movement, but actions do. So if we say the Father has the relation of Father to the Son, we have implied a relative state. Great. But if we say the Father begets the Son, we have implied an action and passion, and suggested motion. So then we subtract motion. We’re left with whatever an action minus its motion is. Great. Habitude of act.

Aquinas wants both: “It was necessary to signify the habitudes of the persons separately after the manner of act, and separately after the manner of relations.”

Why was it necessary to do both? The Bible tells me so.

The Biblical revelation of the Trinity includes both the names of the persons, from which we can discern their relations, and also the acts of the persons, from which we discern their active relations. Aquinas, I think, would want to put this the other way: their actions are active, and the resulting relations are passive or quiescent states. The Father is Father of the Son precisely because he begets the Son. Furthermore, “it is evident that they are really the same, differing only in their mode of signification.” But the mode of signification is what we’re talking about, so we have to be clear about it.

The main point to bear in mind is that both “Father of the Son” and “Father begets the Son” are Biblical statements, and so Aquinas is providing a conceptual gloss on what is essentially a biblical theology project. What I mean is, ultimately if we have an objection to “eternal generation” sounding like a divine origin story, we have to blame God for speaking in terms like this. Or rather, we have to seek clarity on what God does and doesn’t mean by making the Father-Son relation known to us in terms that carry with them ideas of action, motion, and time.

That’s actually why “eternal generation” continues to be worth explaining and defending as an element of the doctrine of the Trinity. Maybe you’re bright enough and creative enough to come up with a more abstract way of putting these matters. But in matters of revelation, we are stuck with what God has made known, and that means we might as well dig in at eternal generation and do the work of explaining it in a way that doesn’t break any of the other theological rules. Habitude is, to my mind, a good resource for that.

_______________________________

Glutton for punishment? Here are some notes on habitude.

Freddoso’s translation of the Summa consistently avoids using the transliteration habitude. Freddoso just renders the key phrase above, “the personal action of producing a person is nothing other than the relationship of the principle to the person who is from the principle—and this is just the relation or notion itself.” This makes me worry that I’m making too much of the little noun habitude. But habitude’s presence at a few key points in Aquinas (and the English Dominican Friars rendering of it) gives me confidence that Aquinas had a distinction in mind that supports this thought project. The Blackfriars translation renders it “condition” here in q. 41.

Habitude shows up in a Trinitarian context again in ST I,q.43, a.1 resp. This is an important section explaining how sentness can be fitting for a divine person. Aquinas says that “the notion of mission includes two things: the habitude of the one sent to the sender; and that of the one sent to the end whereto he is sent.” There is much to say here about the way the sent Son bears his habitude(s) with him.

Habitude shows up in the context of divine names in ST I, q.13, a7, where Aquinas is asking about how God is named using names which imply temporal relation to creatures. Such “names are said of God temporally so far as they imply a habitude either principally or consequently,” but not by referring directly to the divine nature. There is much to say here about predication from time to eternity, and about the kind of relations God has with creatures.

.

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.