A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

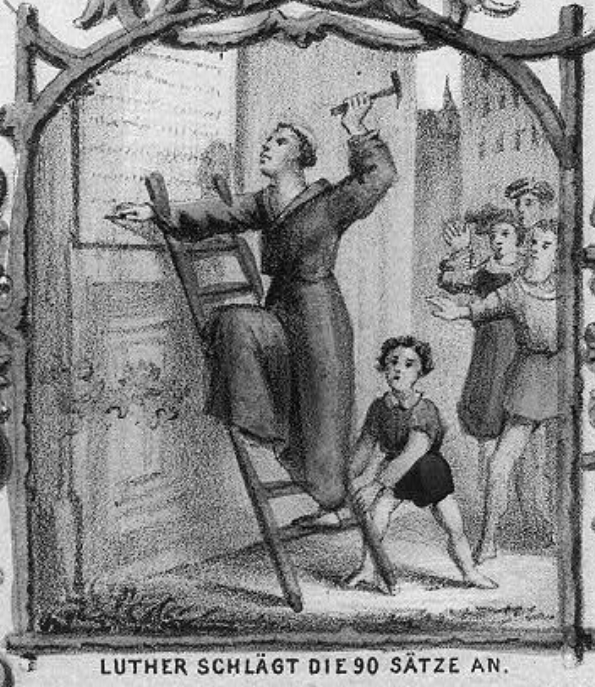

9.5 Theses on Trinity and Soteriology

This is a little exercise I wrote as part of a paper on Protestant Trinitarianism at the 2017 Tyndale Conference in Cambridge. The paper didn’t end up resulting in anything I wanted to publish. But recently I heard some people who ought to know better, musing about how great it would be if there was a way of doing Trinitarian theology that was more robustly Protestant. Suddenly I remembered these rules I had drafted, but had failed to post. So, belated but still in the spirit of holding forth (protestare) the truth, I do hereby post these theses:

9.5 Theses on Trinity and Soteriology

1. God’s identity precedes his actions in salvation history.

2. The doctrine about God’s identity, which is what the doctrine of the Trinity is, should be stateable in a way that recognizes the antecedent priority of God’s identity in himself.

3. God truly makes himself known in the central events of salvation history, and most clearly in the personal presences of the Son and Spirit among us. The only reason we have known God’s triunity is that we have been shown God’s triunity in the Father’s sending of the Son and Spirit.

4. The economy of salvation is a free and gracious opening up of the trinitarian reality of God’s life for our salvation; as he is Father, Son, and Spirit in himself from all eternity, so he becomes Father, Son, and Spirit among us and for us for our salvation.

5. There is no antecedent logical necessity for this economy of salvation to have been. In describing the coherence of the economy of salvation with the eternal identity of God the immanent Trinity , the more fitting category is fittingness. If we feel the need to go beyond this category, any necessity we discern will be a merely post-hoc, consequent necessity.

6. One way to confess the freedom of God in salvation is to confess that God could have freely chosen other configurations of the economy. Hypotheticals are always in danger of abstraction and the mere play of notions, but they can also be helpfully clarifying.

7. Thus God is identified by his premier actions in world history, but he is not simply identified with them.

8. A soteriology is an account of what God has done, ideally developed with alertness to who God is. But a doctrine of God is an account of who God is, ideally developed with alertness to the difference it makes for soteriology.

9. Differences in soteriology should not distinguish between different deities. They hold forth rival accounts of what God does, but not of who God is.

9.5 But they will allow for varieties of Trinitarianism if by “trinitarianism” we mean an expanded field of doctrine in which God’s being and actions are all to be considered in light of each other, with an eye to the different forms in which we will encounter this triune God.

I made the final assertion only worth .5 partly because I wanted to be cute about the 9.5 theses for the 2017 anniversary of the Reformation, but partly because I think this point about varieties of Trinitarianism should be put forth in a way that makes it absolutely clear we are talking about regional variations within a highly unified field of doctrine. What Herman Sasse said of Lutheranism, we can extend to Protestantism as a whole: “there is, thank God, no specific Lutheran doctrine on the Trinity.”

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.