A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

Think of “Trinitarian Missions” Before Thinking of “Economic Trinity”

[The first two paragraphs are background; readers conversant in modern trinitarianism can skip to the third paragraph for the relatively new analysis.]

Under conditions of modernity, a certain way of talking about the Trinity emerged. Theologians began speaking not just of the triune God and the economy of salvation, or the triune God in the economy of salvation, but rather of “the economic Trinity.” A minor adjustment, surely. But the usage made it possible to contrast that “economic Trinity” with “the immanent Trinity,” where “immanent” means remaining within itself, or considered without reference to anything beyond itself. Again, it’s a fairly minor linguistic habit, and it has the advantage of letting us make theological distinctions we sometimes need to make: God in se as distinct from God for us. At its best, the immanent-economic distinction is basically the ancient Christian distinction between theologia and oikonomia, and it functions to alert us to God’s self-sufficient independence (aseity, freedom) from creation and history.

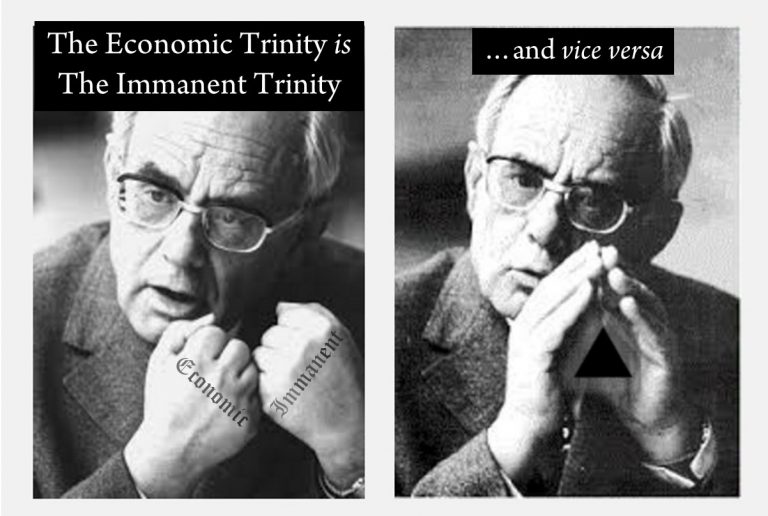

But the distinctively modern turn of phrase is adding the word Trinity to that distinction, twice for good measure. We put the word Trinity on both sides of the distinction, yielding “immanent Trinity and economic Trinity.” Again, this formula invites us to think of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in their own self-contained life (“the immanent Trinity”) and in their turning toward human salvation (“the economic Trinity”). Nobody should imagine two Trinities, just because the word is repeated. On the other hand, if a particular theologian does want to say things about differences in the relations or configurations of the three persons among themselves versus among us, the formula will make it easier to talk about those. Karl Rahner famously insisted that the best sentence we could say about these two configurations is that they are the same; A is B and B is A. Much more could be said (books have been written on this), but the crucial point is that this modern way of talking doesn’t doom you to take a certain position: theologians can use the terms “economic Trinity” and “immanent Trinity” to make different points, disagree with each other, come to terms, and just generally theologize.

Nevertheless, the modern terminology of economic Trinity/immanent Trinity is a tool with a bias, a conceptual idiom with a certain tendency built into it. It obviously prepares the mind to think of two orders or levels, and to stage out a trinitarian configuration on each. As a result, it encourages questions about correspondences between the two levels. When we see something take place between Father and Son in the history of salvation, we can ask, “what is the corresponding immanent-Trinitarian form of this economic-Trinitarian phenomenon?” Take the incarnate Son’s prayer to the Father as an example: when the Son prays (producing verbal expressions of dependence, need, desire, fellowship, etc.), does that exchange have a correlate in the eternal life of God? If so, should we develop our notion of the immanent-Trinitarian correlate by subtracting the creaturely aspects of prayer, and affirming that what passes between the Father and Son immanently is a kind of interaction that is like prayer, but greater?

We can likewise look around the economy for all sorts of Father-Son-Spirit interactions, and develop a kind of research program about each and all of them: what place does this or that salvation-historical Trinitarian interaction have in the immanent Trinity? Does the Spirit lead the Son? Does the Son glorify the Father? Is the Spirit given by the Son or the Father? Is the Son conceived by the Spirit? Does the Father raise the Son from the dead? And so on. What is the immanent-Trinitarian correlate of all these?

How did pre-modern theologians consider all of these questions, before the advent of the modern immanent-Trinity/economic-Trinity conceptual frame?

They mainly spoke of the trinitarian missions: the two movements in which the Father sent the Son, and the Father and the Son sent the Spirit, to bring about salvation. But they thought of these two missions as being grounded in the two eternal processions: the begetting of the Son and the spiration of the Spirit.1 Modern ears, tuned to the frequency of economic-immanent, can hear in the missions-processions distinction the fact that the missions are economic, while the processions are immanent. That is correct. But for classical trinitarian theology, the two internal processions of the Son and Spirit were nothing less than the full scope of the doctrine of the triune God’s eternal livingness. There were not other things going on in the life of God; this was the life. And the two missions to us were not two events among many in the history of salvation; they simply constituted the economy. Everything else led up to or flowed from those missions. The missions were central precisely because of their link to the processions: here is where God became present to creatures in a way that projected forth from the actual triune reality of the divine life. All other divine actions are inseparable outward acts of the Trinity, but the two missions are unique external acts in which the persons are made present, well, personally.2

The modern idiom of “immanent Trinity and economic Trinity” has a pronounced tendency to relativize the two missions, situating them among various other economic events and relations. As a result, moderns have to be careful not to let it lead them to asking silly questions, questions that arise from the framework itself rather than the biblical witness.

Here are two examples. An early responder to Karl Rahner pushed his formula to the limits by arguing that if the economic Trinity is the immanent Trinity, and vice versa, then the economic sending is the immanent procession, and vice versa. But that’s a total collapse of the whole project, obviously –or rather it would be obvious if we were letting the missions-processions schema set the agenda, and only using the economic-Trinity/immanent-Trinity schema to help organize the data within that field. To equate mission with procession is really to let the modern schema dictate bizarre new ways of thinking. A second example is the argument that the Holy Spirit’s role in the incarnation (bringing about the conception of the son of Mary, leading him into the wilderness, inspiring him, etc.) warrants describing the Spirit as the economic sender and immanent source of the Son. Why did such a proposal never emerge in the ancient church? Because the mission-procession schema precludes it. Such a proposal arises from the framework of economic-Trinity/immanent-Trinity. It’s tempting to say that the schema is thinking the theologians rather than the theologians thinking within the schema. But what’s really happening is that the force of the classic missions-processions schema has waned as the economic-immanent schema has waxed.

One solution would be to burn the whole economic-Trinity/immanent-Trinity framework to the ground, and decamp to the old missions-processions schema. But a lot of important theology has been done under the modern schema, some of which has abiding value, and not just as cautionary tale. And the terminology is all over a century of trinitarian theology, so even if it lives on only at the level of seminary jargon, that’s still an afterlife. And even if you were to try to reject the schema outright, it’s likely to outlive you in all those paperback books.

So I think what can be done immediately, and effectively, is to touch base on the venerable missions-processions schema early and often. Consider it to be a more basic organizational framework for the revelation of God in Christ and the Spirit, and always consult it before moving on to the doubled-Trinity way of talking. This will let you use the newer terminology without being used by it.

[Bonus thought: if you’re familiar with Edward Tufte’s analysis of the Challenger shuttle explosion, you know that the engineers were misled by a bad graphical display of the relevant information about the integrity of o-rings in different temperatures over time. Tufte rearranged the data in an alternative chart, simpler and more intuitive, thus visually displaying the danger the equipment was in. NASA had all the data it needed to assess the risk more accurately, but had organized and displayed the data in a way that blocked its visual availability to decision makers. This is a parable for how a mostly harmless organizational schema can make it harder to make orthodox judgements about Biblical information.]

___________________________________

1I’m trimming the terminology here to make it as readable as possible for Christians who affirm the filioque or deny it. Some ambiguity results, but I’m trying to keep the big-picture view evident. Recall that both East and West agree that the Spirit is sent at Pentecost by the Father and the Son; they disagree about what that signifies for the Spirit’s procession. Also, recall that “procession” in the Western tradition can be a group term for the two relations of origin (the Son’s and the Spirit’s), while the East reserves it to pneumatology. The West uses the verb form of Spirit, spirate, to specify the third person’s own mode of origin.

2The best single source for the theology of the divine missions is Adonis Vidu’s The Divine Missions (Cascade, 2021). Vidu’s formulations may be a bit different from mine, but we have substantial agreement. And reading his book is the best way to get the divine missions back on the mental map of trinitarian theology.

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.