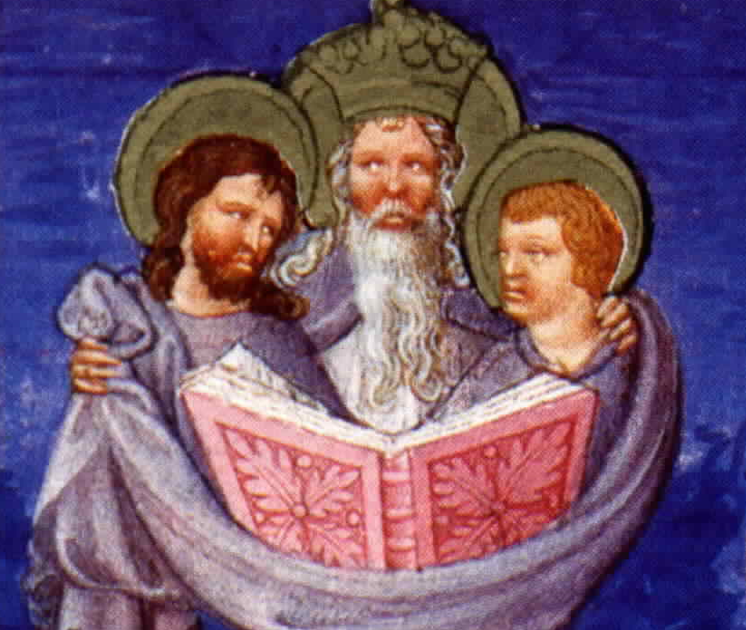

A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

Crescentia Syndrome and the Holy Spirit in Person

Once upon a time, a Franciscan nun named Crescentia (full name: Maria Crescentia Höss of Kaufbeuren, 1682–1744) had a vision. “The Holy Spirit appeared to her in the guise of a youth clad in a gown and a cloak as white as snow, with bare head and curly hair and with seven flames or fiery tongues hovering around his head.”1 Wow!

Crescentia and her monastic superiors sent for a painter, to whom Crescentia carefully described her vision. Under the close guidance of the visionary herself, the painter produced an impressive image that became popular among the nuns and, soon, the surrounding community.

Here’s a version of the painting. There’s the lovely young man, presenting himself and his glory, surrounded by beams of light, tongues of flame, and a shining halo. But those golden-light phenomena are just what we would expect from any purported vision of the divine. What’s really eye catching, and troubling, are the human details involved. Why is he blonde? Why is he young? Why is his nose thin, and his hair parted in the middle, and his posture prancey-dancey? Where do all these details come from?

Good questions. More on those in a minute. First, the rest of the story: The teaching authorities in Rome got involved, pointing out that there were multiple doctrinal and spiritual problems with this image. For one thing, a painting of the Holy Spirit as a cute young fellow could easily lead viewers to think that the Spirit had a body, sort of like the Son’s incarnation but somehow a third-person-of-the-Trinity version. Crescentia replied: “Is not the Holy Spirit also a person within the Holy Trinity? If so, he surely may be represented in the shape of a person.” The pope considered the case and disagreed (his long reply, Sollicitudini nostrae (Oct 1, 1745), is probably Rome’s most detailed instruction about how not to depict the Trinity). Spirit-boy images were absolutely forbidden as unbiblical, unwarranted, misleading, and weird. They were more or less discontinued (but never entirely stamped out, alas), and Crescentia herself was eventually sainted, the Spirit-boy vision being a minor incident in her ministry.

But what, after all, is the deal with those weird details? The hairstyle, the age, the facial structure: where’d they come from? Obviously they came from the lively imagination of the visionary. And that imagination was driven by a kind of spiritual hunger to know more about the Holy Spirit, or rather to know the Spirit more concretely, more specifically, with great precision. “Is not the Holy Spirit also a person?” Then how long can we expect fervent souls to settle for sub-human images like wind, tongues of flame, a dove descending at the baptism of Christ? Why not conjure up more vivid, detailed, and solid ways of picturing him?

The answer should be stated definitively: God the Holy Spirit, the third person of the Trinity, has made himself known exactly as he desires to be known. The task for believers is not to make up imaginary new characteristics in an effort to force him to seem as vivid to us as the incarnate Son. The task is to receive the actual revelation, delight in what it provides to our minds and hearts, and learn to accept the revelation for exactly what it is, including where it stops. That’s the task.

The same problem, Crescentia Syndrome I call it in pneumatology, pops up whenever we let our imaginations kick into detail-generating mode, rolling in a fine frenzy from earth to heaven, and bodying forth stuff that just ain’t right (to, um, paraphrase Shakespeare). The same insatiability of imagination has led artists occasionally to depict the Trinity visually as (1) a Jesus-reminiscent figure, (2) a venerable senior citizen, and (3) some pretty young fellow with excellent hair. Now, we may feel a little guilty for seeing the elderly king figure and thinking, “Oh, it’s God the Father,” since God the Father is not an old man. But at least “old man” is straight from central casting, so we don’t wonder where the details come from. The Spirit, on the other hand: the arbitrariness of assigning him an age and hair color is absolutely palpable.

Most of us aren’t in the business of making paintings of the Trinity, or of the Holy Spirit, that call for disciplinary intervention from a Pope. But many of us feel the tug of wishing the Holy Spirit were more vivid, and have to learn to rest in what he has actually made known. Here’s how I put it in my book The Holy Spirit: An Introduction:

As we strive to know the Holy Spirit the way he makes himself known in Scripture, we are constantly tempted to add a few details, to quietly nudge the Spirit in the direction of being more immediately vivid than how we meet him in Scripture. We wish the Holy Spirit were, frankly, more of a character, with more lines of dialogue and a better-defined personality profile. We should be vigilant about this temptation and should theologically repent when we see specific ways we have given in to it. For some of us, abstaining from imaginative Spirit-concretizing may be a serious spiritual struggle, but there is a great blessing on the other side. The real Holy Spirit is better than the one we trick out in imagined details, for many reasons, but fundamentally because he is real and has made himself known exactly as he sovereignly chose to.

Crescentia Syndrome is a thing worth avoiding, and the way to avoid it is to be deeply satisfied with real, Biblical knowledge of the Holy Spirit, in person.

_______________________

1Peter Stoll, “Crescentia Höß of Kaufbeuren and her Vision of the Spirit as a Young Man,” at Stoll’s Augsburg University site. See also François Boespflug, Dieu dans l’art: ‘Sollicitudini nostrae’ de Benoît XIV (1745) et l’affaire Crescence de Kaufbeuren (Paris: Cerf, 1984).

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.