A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

Parergon Management

Sometimes when you’re working on a big project, you find yourself spinning off, almost by accident, little sub-projects. These can be of various kinds: some are distracting sidelines; some are sub-sections that are fine but just don’t fit the flow of thought; some are ideas that develop their own heft and center of gravity and just spin away. There’s a word for those little excrescences in your productivity: they (plural) are parerga, or each of them is a parergon. A little by-work, that developed alongside the large, main work.

People used to use this word in literary or artistic contexts: if Michelangelo made a small painting while working out ideas for the Sistine Chapel ceiling, you would call that little stand-alone painting a parergon of the big project. So it’s different from a preliminary sketch, because sketches are practice for the main work. A parergon isn’t so much practice as something that grows out of actually working. In a literary context, Dickens might think of a funny situation while working out a large plot; he might set that aside to finish up later as a short story, and we would call the resulting story a parergon. A parergon is also not quite a sequel, though if it’s a very minor sequel that contains some leftovers from the main work, it might qualify: “Screwtape Proposes a Toast” is probably slight enough to be considered a parergon to The Screwtape Letters.

That’s a parergon. I’d be glad to know a better name for it, because Things need Names, and parergon is an almost comically awkward word to use (Kant and Derrida used the word in a philosophical context, but we needn’t let that bother us, need we?). Knowing a word for it helps you spot it. And if you’re working on projects, I bet you’ve got a parergon or two.

What should be done with a parergon? It depends on how good they are, how poorly they fit the main project, and what other opportunities you’ve got coming your way.

If you are urgently working toward completion of the main project, a parergon is usually a distraction. In fact, chief among the benefits of knowing a label for it is knowing that you are allowed to set it aside and get on with your main task. Until you’ve recognized it as a parergon, you might spend A WHOLE DAY trying to make it fit into the main project. A parergon always feeeels like it belongs; that’s because of its organic origin from the main body of work. When I was writing my first book-length project, and it seemed to me that life or death hung in the balance of its successful completion, I kept a desk drawer into which I could throw every parergon. I’d write them on 3X5 cards, toss them in the otherwise-empty drawer, and slam the drawer shut. It was a little drama to act out the truth that (a) this was an idea that was worth recording, but (b) it was not to be pursued at this time. I no longer keep a drawer for them; I write them in a notebook or in a notes app on my computer.

Later, you can go back and look through the discarded parerga to see which ones you’re still interested in developing. Some of them turn out to have been stinkers all along. Some are okay but have lost their magical draw.

But some of them –and this is the next part of parergon management– are great, and you can develop them according to their own logics and possibilities now that they are safely free of the main project.

When I was writing a short book about the Holy Spirit, I kept generating more ideas than I could possibly fit into the scope of the project. I also knew that it would be about a year before the book was published, and that by that time I would be less mentally absorbed in that doctrine, but would still need to share some thoughts and ideas as part of the book’s release and promotion. So I went back to parergon management 101: I herded those extraneous ideas out of the main workflow, and kept them in a file for use after the book was published. Once the book was available, I started tweeting some of those extra quotes and ideas, and blogging others. In a few cases, I’d come across a parergon from the Spirit book that was hefty enough to work up into another writing project for actual publication. But for the most part, what I call a parergon is small enough to share less formally.

Speaking of smaller scales, here’s a handy application of parergon management. Let’s say you’re writing a paper to be presented at an academic conference. Word count & delivery time are crucial, but you’ve got lots of material. Scan for parerga: which sections seem very important to you, but are relatively separable from the main body of the work? Cut those sections. Cut them and keep them on hand. End your paper on time, or 90 seconds early. And then, during the questions period –which you actually have time for, because you edited out all that great extra stuff– you can use the excised material. Think of it: you will actually be “so glad for that question” because you’ve got remarks on it ready to go. This is one of the secrets to a lively and gratifying Q&A exchange, from the speaker’s side. You do have to be quick on your feet to match the questions to the topics you’ve got on reserve, and you want to make sure not to behave like the kind of politician who has a set of talking points that you’re going to pretend are actual replies (“I’m so glad you asked that tough but fair question. In response, here is my standard position verbatim.”) And of course you have to have been right about whether your precious parergon was in fact naturally connected to the main topic. But when it all comes together, your Q&A period can actually be an enriching encounter instead of an awkward postlude for mumbling “I didn’t really look into that aspect of it; I just have what I wrote down here already.”

_____________________

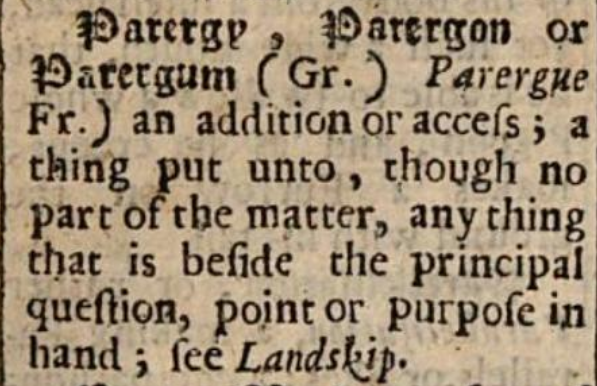

Image: definition of parergy, parergon, or parergum, from Blount’s Glossographia (London, 1661), a book “very useful for all such as desire to understand what they read.”

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.