A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

“The Father is Greater Than I”

In John 14:28, Jesus says “the Father is greater than I.” There is one wrong way to understand his meaning, and two right ways.

The wrong way is the Arian heresy or some other kind of subordinationism. People who take this view think that with these words Jesus intends to teach that the Son of God is of a lower status or order of being than God the Father. He’s doing some ontology, and putting himself ontologically lower than the Father, claiming to be less than God in the sense of not God, not truly or fully God.

But what about the two right ways of understanding “the Father is greater than I?” They are complementary rather than contradictory. The first is that Jesus is referring to himself according to his human nature, assumed by incarnation: the Father is greater than the Son’s humanity as incarnate. The second is that Jesus is referring to himself according to his personal or hypostatic identity as Son of the Father: the Son is fully divine (coessential, coeternal, coequal) but stands in a relation to the Father that orders him after the Father.

So the Arian interpretation is out, but the incarnational and hypostatic answers are both in. But the trick here (you may have sensed some fancy foot-work going on) is that what it means for the Father to be “greater” is completely different in the two right answers. The incarnational answer acknowledges him to be extremely greater, as much greater as the creator is greater than the creature; the hypostatic answer acknowledges the Father to be greater in the very different sense of being the principle of the Son: a distinct person, and the person from whom the second person has his identity.

The church fathers line up on different sides of this discussion, depending on the contextual pressures, or what kind of questions they’re trying to answer. As you can imagine, if there’s serious Arian pressure impinging on them, they snap to the first answer, and rather aggressively so. But if they’re dealing with trinitarian confusion, they’re more likely to explore the second answer and dwell on personal distinctions within the one divine essence.

Speaking of context, what about the textual context in which we find this passage, John 14:28? That also demands attention, les we lift a half dozen words out and ignore the situation and setting in which Jesus spoke them. On the face of it, that would be pretty obviously bad methodology. The context, as you may recall, is Jesus teaching the disciples about his upcoming departure, and how they ought to feel and think about it.

But now we’ve piled up a lot to talk about: John’s Gospel, the incarnation, the Trinity, the history of interpretation…

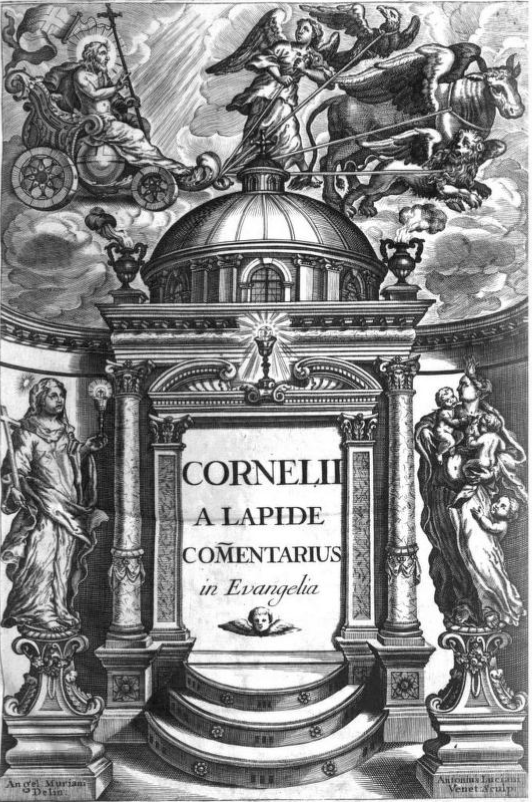

I recently came across a helpful exposition of all this, in the very large commentary on Scripture written by the Jesuit scholar Cornelius Lapide (1567–1637). He gives the issue about a thousand words (at least in the English translation, which I think may be somewhat abridged), and I like the way he works patiently through the options.

First Lapide eases into the hard passage by linking it smoothly to the words immediately preceding it. “If ye loved me, ye would rejoice that I said ‘I go to the Father.'”

If ye loved me, etc. The apostles did love Christ, and therefore they were troubled at His going away. When therefore Christ says, if ye loved Me, He speaks after the manner of men. It is the way of consoling friends when they are sad at the departure of a friend. If you showed Me, O ye Apostles, what true and sincere love demands, ye would not grieve but rejoice at My departure, for My going away will be exceedingly profitable to Me, yea, and to you likewise. For I am going to the Father who is greater than I, i.e. I am going from consorting with men to God, from human misery and contempt to Divine felicity, exaltation, and glory. I am going to prepare a place for you, to which in due time I will bring you. So Cyril.

In one sense, everything’s already answered here in advance, and for that matter Cyril of Alexandria had already sorted it out in the fifth century (“So Cyril”). The incarnate Son is returning to the Father, and to be with the Father is greater than to be among creatures. But a moment’s reflection shows that the Son has only come from the Father and can only return to the Father according to his incarnation, so already we see here the first moves in giving the incarnational answer. The Father is greater than the Son in the sense that the completion and fulfillment of the Son’s incarnate mission is greater than the conflict and contradiction in which he lived his life among fallen humanity. But this is a bit subtle, so Lapide will make the whole thing fully explicit.

For My Father is greater than I. This was the great stronghold of the Arians, by which they sought to prove that the Son was not God, but the highest creature of God; but SS. Athanasius, Augustine, Basil, and the rest of the Fathers, admirably reply to them, that Christ is here speaking of Himself not as God, but as man. For as such He was less, not only than the Father, but even than the angels.

And that Christ is speaking thus is plain from hence, that He gives the reason why He is going to the Father: because, He saith, My Father is greater than I. Now Christ goeth to the Father, in that, as man, He ascendeth into heaven. For as God He is alway in heaven with the Father. Wherefore S. Augustine saith, “He went, in that He was in one place: He remained, in that He was everywhere.” That is, He went through His Humanity, He abode through His Divinity. Therefore His Father was greater than He in respect to His Humanity, not His Divinity.

There it is: the incarnational answer, in an anti-Arian context. But Lapide isn’t just swatting Arians or establishing a Chalcedonian, two-natures answer. He really warms to the teaching that we should rejoice over the successful completion of Jesus’ incarnate ministry, and should lift up our hearts to what the Son has accomplished in his mission:

The meaning then is, Ye must rejoice, O ye Apostles, at My departure, because I go to the Father, and ascend into heaven to greater honour and dignity, that I may obtain from the Father, for Myself and for you, the rewards of My Passion, even a seat at the Father’s right hand, and the empire of the universe, the adoration of all the angels, and the conversion of all nations to My faith and worship: and for you the Holy Ghost and all His gifts, armed with which ye shall conquer the whole world for Me and for yourselves, and bring it with you to celestial glory. For those things, which are far greater than what ye have as yet seen and received, I will ask and obtain when I go to the Father.

Only after all this does Lapide make a turn from the incarnational answer to the hypostatic answer. He does so with alacity:

Some fathers, moreover, in order to give a complete answer to the Arians, answer more subtilly, but intricately, that the Father is greater than the Son not only as He is man, but also as He is God,

because the name of Father seems among men to be more honourable than the name of Son. For a father is the beginning and cause of a son. The Father therefore is greater than the Son, not in magnitude, nor time, nor virtue, nor dignity, nor adoration, but in respect of a certain honour amongst men, i.e. in respect of origin, because the Father is the origin of the Son. So S. Athanasius (Serm. cont. Arian.), S. Hilary (lib. 9, de Trin.), &c.Although with reference to Divine things, filiation, from whence is derived the idea of sonship, is something as excellent and as honourable as is the idea of paternity in the Father. Indeed, as the Son hath from the Father that He is the Son, so in turn the Father hath from the Son that He is the Father. For the Father is He who hath the Son. Wherefore in this case, that passive origin which is in the Son is in itself as worthy and as honourable as that active origin which is in the Father. For it is as great to be Begotten God as it is to beget God. Therefore it is as great to be the Son as to be the Father.

Lastly, each hath altogether in personality the same Divine Essence, the same majesty and omnipotence. Wherefore one cannot be greater than the other. “Greater,” says S. Hilary, “is He who gives by the authority of a giver, but He is not less to whom it is given to be One (with the Giver).” Greater, i.e., in the estimation of men, not of God. Wherefore Maldonatus thinks that Hilary and some others have conceded too much to the Arians. And Damascene (lib. I, de Fid.) corrects them thus, “The Father is greater, not in nature, nor in dignity, but only in origin. (See Suarez, lib. 2, de Trin. cap. 4.) And in my opinion this was the teaching of S. Hilary.

You see here the whole trinitarian conceptual apparatus. Father and Son are correlative terms, relationally distinguishing the two persons, and distinguishing them in such a way that while each person depends on the other for their identity (the Father wouldn’t be Father without Son, or vice versa), yet the Father is first (the Father is principle of the Son, but not vice versa). Sonship is not deficiency; in the case of this divine sonship, it is perfect equality. You can also see Lapide sorting out which patristic voice took which side, and why; as far as he is concerned, they were all right as long as you read Hilary the right way.

With all this as a kind of foundation, Lapide makes one more distinction about how the words “Son” and “greater” are functioning here analogically. The Arian error is based on taking the revealed image of “son” too univocally; that’s why Arius thought “if the Father began the Son, there must have been a time before he was begotten, and before he was begotten he didn’t exist.” But Lapide argues that you can’t take “son” and “beget” as if they are simply describing creaturely realities in that way:

Moreover, the analogy of the Divine compared with human generation is so entirely different as to refute the Arians. For in things human the father is greater than his son.

1st. Because he is prior, and senior to the son.

2d. Because he is greater in stature and bulk, for a grown-up man generates a little infant.

3d. Because he produces a nature numerically different from himself, which he communicates to his son. Wherefore he is greater than that nature as being its author.

4th. Because of his own free will he begets a son. For it was possible to him not to have begotten.

So a human son might say “my father is greater than I” and mean those four things.

But in things Divine the manner is altogether different. For the Father is greater than the Son neither in age nor size: neither does He beget a Deity different from His Own, but communicates to the Son the same Deity which He Himself has. Neither does He beget of His own will, so to say, but of the natural fruitfulness of the Divine Nature He produces a Son the equal of Himself, nor can He produce another.

Lastly, S. Cyril, in the Council of Ephesus, proves that the Father is greater than Christ in so far as Christ is man, but not in that He is God, after this manner:— “We acknowledge Him (the Son) to be in all respects as the Father, to be incapable either of turning, or of change, and to have need of nothing, a perfect Son, like unto the Father, and differing from Him only in this respect that the Father is unbegotten. For He is the perfect and express Image of the Father. And it is certain that the Image ought fully to include all those things in which the Pattern itself, which is greater, is perfectly expressed, even as the Lord Himself hath taught, saying, the Father is greater than I.”

Divine Sonship, in other words, does not undermine but establishes absolute equality. In order to understand Jesus’ teaching, “the Father is greater than I,” we need to affirm the one substance of God (shared by Father and Son), distinguish the persons by eternal generation, and recall the climactic place in the history of salvation at which Jesus draws our attention to this.

All of this can be found in Cornelius Lapide’s Great Commentary, volume 6, 108-110; the work is voluminous and Lapide’s method does not always yield such happy results. But for John 14:28, Lapide’s commitment to synthesizing traditional teaching while also attending to the words of scripture in their own context really pays off.

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.