A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

“Many a Bridge:” Reading Tennyson’s In Memoriam in Cambridge

The Torrey Cambridge summer course reads short works by authors with a Cambridge connection. The works chosen this year are all related to themes from Colossians, so we’ve read sermons by Simeon (preached at Holy Trinity & Kings College Chapel), commentary by John Davenant (from his first course taught here as Lady Margaret Professor of Divinity), and C.S. Lewis on how reading old books is like travelling to a foreign country.

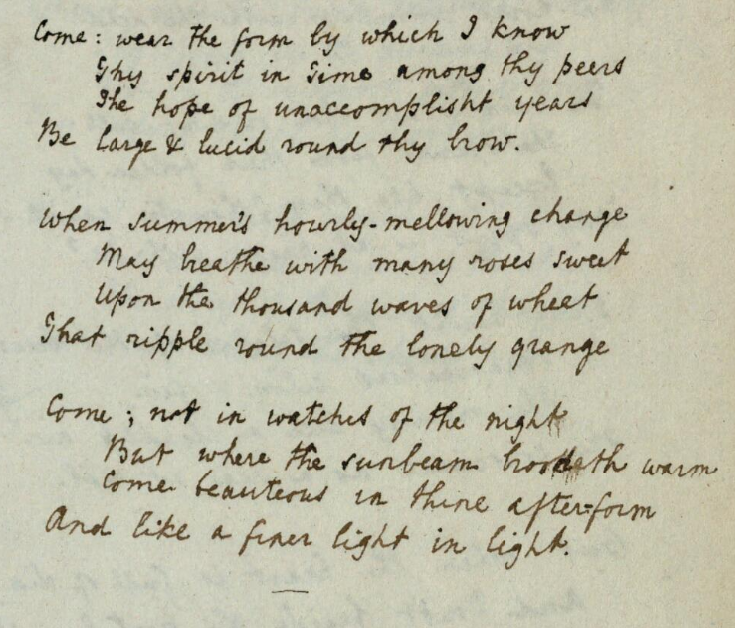

We also read Alfred Lord Tennyson’s great book In Memoriam, a set of 131 poems about grief and faith. In Memoriam was once very well known and greatly esteemed. Of all the books we cover in our summer curriculum, it’s the one most likely to earn a secure spot on an official “Great Books” list, both by reputation and by inherent worth.

In Memoriam is a very Cambridge book in multiple ways. In it, Tennyson mourns the death of his friend Arthur Hallam, who he met at Trinity College, Cambridge. The 87th poem in the book evokes scenes from their college days:

I past beside the reverend walls

In which of old I wore the gown;

I roved at random thro’ the town,

And saw the tumult of the halls;And heard once more in college fanes

The storm their high-built organs make,

And thunder-music, rolling, shake

The prophet blazon’d on the panes;And caught once more the distant shout,

The measured pulse of racing oars

Among the willows; paced the shores

And many a bridge, and all aboutThe same gray flats again, and felt

The same, but not the same; and last

Up that long walk of limes I past

To see the rooms in which he dwelt.

Our summer students, having spent over a week in town, will match these words to clear images of the tree-lined River Cam, its punts and willows and many bridges. They’ll also have good memories of class time together, in which they talk about big ideas and great texts, and perhaps have occasion to look at each other as Alfred looked at Arthur during the give and take of class discussion:

Where once we held debate, a band

Of youthful friends, on mind and art,

And labour, and the changing mart,

And all the framework of the land;When one would aim an arrow fair,

But send it slackly from the string;

And one would pierce an outer ring,

And one an inner, here and there;And last the master-bowman, he,

Would cleave the mark. A willing ear

We lent him. Who, but hung to hear

The rapt oration flowing freeFrom point to point, with power and grace

And music in the bounds of law,

To those conclusions when we saw

The God within him light his face…

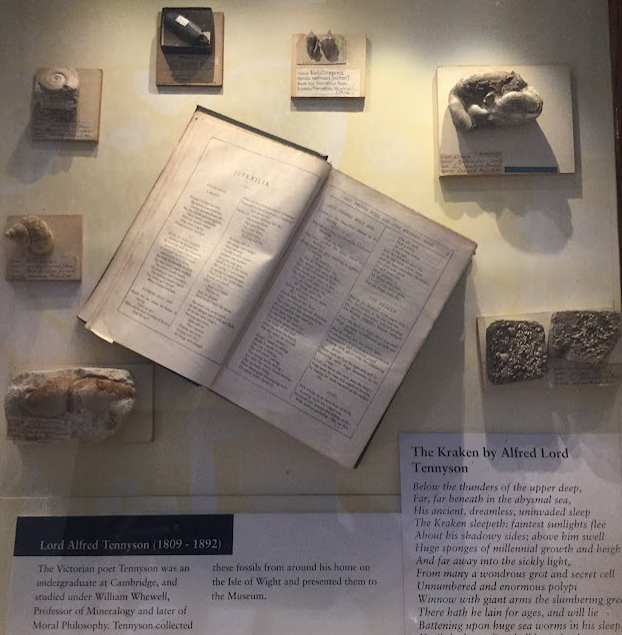

In Memoriam is also a Cambridge poem because in it, Tennyson takes up and considers the scientific education he received in Cambridge. Beyond the student experience of fields chapels and and punts and philosophy arguments (the “college fanes,” “high-built organs,” “many bridges,” and “gray flats,” Cambridge was for Tennyson the place of science. Earth sciences in particular drew his attention: geology, mineralogy, and paleontology.

So when Tennyson wrote a long set of poems over the course of more than a decade, grieving the death of his dear friend from student days, he wrote a poem shot through with local color and all the implications of the scientific view of the natural world. His grief is the world’s grief, and as he makes his way through the darkness, the poet conjures and analyzes a cosmos in which life itself is on that same trek. It won’t quite do to say he’s thinking Darwinianly, because Tennyson’s touch-points and key ideas are more directly stimulated by Lyell and other earth-science figures whose names loom less large for most people today. But many of the same issues are at stake for him: how to account for the massive suffering and death built into the story of life considered in geological “deep time.”

One way to think of In Memoriam is as the result of a fairly orthodox Wordsworthian nature poet who tries to revisit the “spots of time” in nature that have the power to heal his soul, but finds them drained of their renovating virtue by the findings of Victorian science. He doesn’t deny what he has learned in the lab. He tries to take it all in to a larger synthesis, so that head and heart can “make one music as before, but vaster.” He has to get bigger to outflank the tragedy; Growth into a higher synthesis is the only way forward.

In Malcolm Guite’s fine study of Tennyson as a Cambridge poet, he reads In Memoriam as the story of a struggle for faith that incorporates doubt. That is surely correct. Guite judges the struggle to be a successful one, and takes In Memoriam as a testimony to Tennyson’s belief in the strong Son of God, Immortal Love. As I read the work (and on this trip through it with students I was more struck than ever by how sheerly “canonical” and Great Books-y In Memoriam is– there is Augustine and Dante on every page, along with the more obvious Plato and Wordsworth!), Tennyson’s faith is not just wounded by his suffering, but its quality is diminished. His belief in God as love may have grown in scale and stretched out across a vaster field of deep time to cosmic proportions, but in obedience to Boyle’s law about gases, it also thinned out rather drastically. Tennyson’s faith is comprehensive and cosmic (and from that victory there is much to be learned), but vague and nearly formless (and this spontaneous degeneration is cautionary). We can love Tennyson’s work and be deeply moved by it while confessing that parts of it are gassy. Critics have long admitted this about his poetic diction: when it soars, it rises to the highest level and accomplishes feats that rival the best that has ever been said or sung, but on those occasions when it falls flat, there is nothing more feeble or bathetic –and he uses the same techniques to achieve both ends! Something analogous can be said of the character of his Christian faith.

Then again, if I had to gamble on whether Malcolm Guite or I was more correct about a major poet’s overall project, I’d bet on Guite, sight unseen.

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.