A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

He Set Forth his Good Pleasure in Christ (Eph 1:9)

As I work on my theological commentary on Ephesians, I usually follow pretty predictable tracks. Ephesians has drawn centuries of excellent interpretation, including some powerful recent scholarship from professional exegetes. But sometimes I find myself “falling down a hole,” stumbling into discoveries I had not expected, and catching glimpses of things none of the commentaries have prepared me for. On those occasions, I give myself permission to follow the subject matter where it leads, and to write freely without worrying about word count or, frankly, audience. Something like that happened this week with the inconspicuous words “which he set forth in Christ” in Eph 1:9. It got hold of me, and I produced about 1400 words of comment on a phrase that is only four words in Greek. No doubt I will edit this down to something briefer before publication. A sense of due proportion is very important, and this is disproportionate attention to a small text. But I am (verbosely) making up for neglect. Anyway, I wanted to share it here on the blog in case it doesn’t finally make it into print.

According to his good pleasure that he set forth in Christ

This little phrase (hēn proetheto en auto) has drawn less attention than it merits. The justly famous claim about God’s oikonomia in the next phrase has perhaps distracted interpreters from apprehending just how much is already taught here in this claim about a divine setting-forth. What if the term “God’s economy” had not become the favored way of evoking this great mystery, and “God’s setting-forth” had instead won prominence?

God has set forth his good pleasure en autō, which could refer either reflexively back to God “himself,” or demonstratively to “him,” that is, Christ. If autō means himself, then the idea is that God alone (not precisely the Father, but the one God considered absolutely) “formed this design, for He is surrounded by no co-ordinate wisdom.”[1] But if autō means “him,” Christ, then the idea is that the Father has set forth his good pleasure in the Son. While KJV offered “in himself,”[2] several other translations adopt the “him” view so decisively that they replace the pronoun with the name Christ here to guide the reader (NRSV, ESV, NIV).

At the highest theological level, we might venture to say that since en autō directs our thoughts into the inner life of God, it understandably hovers between the inseparable deity “himself” and the Father-Son relation.[3] Divine action en autō without further specification simply throws us back onto God as the agent, where there is no contradiction between ascribing agency to the one God essentially or to the Father and the Son relationally. To say that the triune God sets forth the divine eudokia is not actually different from saying that the Father sets it forth in the Son through the Spirit.

But there is a further fullness in this phrase ēn proetheto en auto, and it lurks in the verb protithēmi. The verb is syntactically important as the hook from which hang both of the following prepositional phrases: not just “in him” but also the more expansive “as an oikonomia” etc. The transitive verb can mean either to intend/purpose something or to set something forth.[4] In the NT it only occurs two other times: Rom 1:13 and Rom 3:25. The two occurrences happen to display the alternative senses helpfully. In Rom 1:13, Paul says that he “often intended to come” to the Romans. In that report of his (frustrated) travel plans, the pro- in protithēmi may have a temporal sense (projecting a plan for the future) or an imaginative sense (proposing an idea, setting it out there for consideration), or both. On this model, Eph 1:9 teaches that God framed or purposed his eudokia internally. This sense of the verb aligns well with the fact that protithemi is the root of the noun prothesis, purpose, which occurs nearby in 1:11 (predestined “according to the purpose”).[5] On this view, Paul is nearly saying that God has purposed with a purpose; it is characteristic of Ephesians to say that God verbs with cognate nouns.[6] We can hardly object that this would be too great a pile-up of language about purpose and will; it is also characteristic of Ephesians to repeat repetitively.[7]

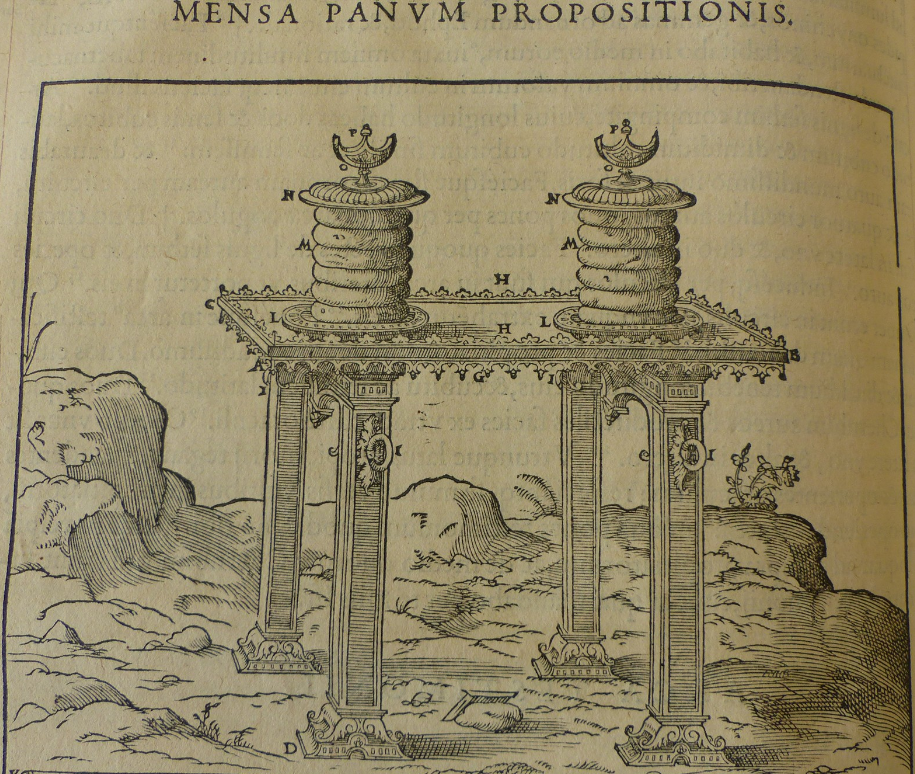

But in Rom 3:25 Paul uses the same verb in a more soteriological context to say God “put forward” Christ Jesus as “a sacrifice of atonement by his blood.” Here God’s action is some sort of manifesting, arranging for display, bringing out into public, or putting into effect. If Eph 1:9 uses the verb in this sense, Paul is saying that God took the step of enacting the display of his eudokia in history. In context, Eph 1:9 has important similarities to Rom 3:25: in both, redemption, blood, and forgiveness of sins are mentioned.[8] Furthermore the verb protithēmi may retain a certain liturgical (though not sacrificial) aroma from its LXX use. The unleavened showbread is rather elliptically called in Ex 29:23 not bread but protetheimenōn, something arrayed or set forth in God’s presence. In Ex 40:4 the priest is told to arrange what is to be arranged, prothēseis tēn prothesin, on the table.[9] If Paul used the verb “set forth” with such connotations in mind, he would not quite be calling Christ the showbread. But he would be saying that in Christ, God’s good pleasure has been arranged with an arrangement, like two rows of six loaves set forth before the face of God in the holy place. Hearing “set forth” as arrangement language would lead naturally into the next phrase, where Paul speaks of God’s ordered economy or executed plan.

It may seem that interpreters who choose “he set forth” would also choose “in Christ,” while those who choose “he purposed” would also choose “in himself.” These decisions do seem to cluster in this way between outer-action and inner-choice perspectives. But no. We do have the pure types “he set forth in Christ” (NRSV, ESV) versus “he purposed in himself” (KJV), but also the mixed types “he purposed in Christ” (NIV, CSV) and “he purposed in Him” (NASB).[10] Clint Arnold argues for a mixed type, translating the verb “he designed” (an inward purposing) and the prepositional phrase “with Christ” (not in himself but along with the Son). “It would be wrong for us to think of God as devising this plan in isolation. He formed this amazing redemptive plan in close connection and communication with the preexistent Christ,” so that “with Christ” here “speaks of the union and intimacy of the Father and the Son prior to creation.”[11]

Goodwin’s hermeneutical maximalism[12] would direct us to accept either the greatest possible interpretation (though in this case, which would that be?) or else not to choose, but to take the interpretation that lets us affirm all the options. That reconciliation of all possibilities might just be viable in Eph 1:9. The little phrase hēn proetheto en autō contains multitudes, because it is in fact oddly poised between the infinite depth of God’s resources and the outflowing embassy of salvation. If God set forth his good pleasure in Christ outwardly, that presupposes that he first purposed his good pleasure in himself, inwardly (though no Christian interpreter should take “in himself” to pick out the first person in a way that shuts out the second). “The purpose takes effect in Christ, but it is conceived in God’s own heart.”[13] The relation between God and his good pleasure is that he proposes it to himself in himself, setting before himself a plan; on this basis he sets it forth in action in the world, arranging its elements before his own presence and showing them well ordered on the table of salvation history. “He set forth his good pleasure in Christ” is thus parallel to those other late-Pauline expressions in which the meaning of Christ’s work is described as if from a distance: “the grace of God has appeared,” (Tit 2:11) or “the goodness and loving kindness of God our Savior appeared” (Tit 3:4). It is another of Paul’s ways of tracing out the pre-cosmic presuppositions of the history of salvation.

[1] Eadie, 50.

[2] Furthermore there is a minor textual issue here, with a few papyri reading heauton (emphatically reflexive); see Hoehner, 215. Several older commentaries consider hautō the correct reading (Eadie 50, Ellicott 12, Meyer 46-47).

[3] As Augustine would say, it depends on whether we are predicating essentially or relationally. Augustie, On the Trinity, book 6.

[4] BDAG 889.

[5] It also occurs later in 3:11 (“eternal purpose”).

[6] See p. ___ above at “blessed us with a blessing” and a complete list of the constructions.

[7] However, one reason not to translate eudokia (1:5,9) as purpose is to keep it from dissolving into synonymity with prothesis (1:11). In fact, ESV is rather forced to say that what God does with his eudokia=purpose is to set it forth, since it would be confusing to say purpose twice in a row, but representing two different Greek words.

[8] Cohick, 106.

[9] See Hoehner, 215 for a brief survey of LXX usage. As for later patristic Greek usage, Lampe’s Lexicon offers and illustrates two meanings: (1) to determine or purpose, and (2) the liturgical meaning “set forth in offertory.”

[10] There is also the idiosyncratic “he has set his favor first upon Christ,” proposed only by Markus Barth, whose main argument in defense is that this phrase should reflect the Barthian doctrine that “election is…first and essentially the election of the Son.” Markus Barth, I:85-86. Quotation from 86.

[11] Arnold, 87.

[12] See above, at p. __.

[13] Eadie, 50

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.