A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

Re-Alphaed and Omegaed (Preston)

Christians are supposed to develop spiritual strength. It’s not just that they’re empowered by God from outside and above themselves (though that’s absolutely true, praise God!), and it’s not just that they have natural powers and abilities (though that’s relatively true, though personal mileage may vary). In addition, there is such a thing as spiritual strength. You might think of it as a middle category between outside help and natural ability. It’s a real, theological thing. Paul prays for it in Eph 3:16: “That God might grant you according to the riches of his glory, that ye may be strengthened by his Spirit in the inner man.” (Geneva Bible translation because I’m about to quote an author contemporary w/KJV 1611.)

It takes a fine theological reader to notice that “strengthening the inner man” in this passage refers to this third category of power: not just God’s own power, and not just a special boost to natural powers, but what we might call the cultivation of spiritual strength.

The fine theological reader who explicitly called it “spiritual strength” is John Preston (1587-1628), in his book The Saint’s Spiritual Strength (London, 1634) (Google Books, EEBO text), an extended gloss on Eph. 3:16. In addressing this passage contextually, Preston points out that Paul is praying for people who are already believers, that they would attain a deeper or fuller experience of their spiritual blessings. He is praying that they would grow stronger inside.

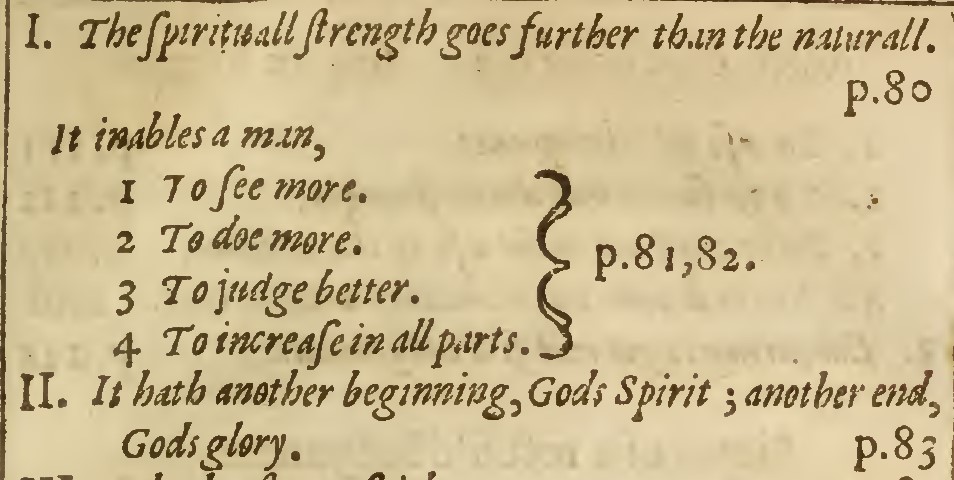

Preston’s sermonic work on this idea is long and full of truly edifying sidelights (not to say distractions), so let me just pick out one key point that I think gets to the heart of his insight about spiritual strength. Spiritual strength takes natural human abilities and recontextualizes them so radically that it transforms them. For Preston, grace doesn’t destroy nature but elevates it (he says this explicitly not just here, p. 80, but throughout his work, whenever he grounds his ethics in his theological anthropology and its doctrine of creation, as one does). “Grace elevates nature” might be the most abstract possible formula for making this point, but I mention it to tag the base of traditional ways of talking.

Preston puts it much more vividly here by saying that spiritual strength differs from natural strength “in the beginning and ending of that strength: it hath another Alpha and Omega.” (83)

Spiritual strength outflanks natural. It begins in another principle and ends in another terminus. You can picture this by keeping your mental focus on any virtue and then expanding your attention to consider the principle from which it proceeds (alpha) and the telos toward which it moves (omega). Sanctification is a matter of having your actions and powers increasingly re-principled and re-teleologized.

Start with analysis of the principle: “The strength of the spirituall man is wrought by the Spirit and Word of God.” Because “the principles of religion” are “taught him out of Gods Word, hence there is a spirituall strength conveyed into the soule.” (83) What Preston provides here is a way of analyzing actions by tracing them back to their origins. There is something mysterious in this, of course, and Preston doesn’t mean to redirect our attention simply to discerning personal motivations. He is actually asking for us to discern the objective sources of our actions. Bluntly, do we do things because we have been instructed to do them by God, in his word? If so, then our action proceeds from an inner man instructed by a spiritual principle.

Preston is well aware that principles are invisible and the inner man is inner. So he instructs us in how to infer principles in part from their results. And here I want to hand you over to Preston’s own prose, asking you to read attentively:

Examine whether there has followed a comfortable assurance of God’s love in Christ, which has not only wrought joy and comfort against the former fear, but also a longing desire after Christ and holiness. Therefore if the holiness that is in you be thoroughly wrought, it does proceed from the Spirit, for this orderly proceeding of the Spirit does make it manifest.

But as for the natural strength, it has not such a beginning; it is not wholly wrought by the Word. It may be [a person with such natural strength] has been a little humbled and comforted by the Word, but it is not thoroughly and soundly wrought by the same Word: [It] is a mere habitual strength of nature picked out of observations and examples. (84; spelling & punctuation updated)

Spiritual principles produce joy and comfort, plus longing desire. Why? Because “thoroughly wrought” holiness proceeds from a holy principle. And that principle is “God’s love in Christ,” which is to say, it is the same principle from which the Holy Spirit proceeds.

Am I over-reaching by (predictably) finding the dynamics of God’s own triune life in this phrasing? I don’t think so. Preston says that the principle behind consistent holiness must be the Spirit; such holiness must “proceed from the Spirit,” because “this orderly proceeding of the Spirit does make it manifest.” What order? “God’s love in Christ,” a Father-Son order as the principle of the principle of our principles.

But even if you don’t want to trace this all the way back into trinitarian relations (or you’re not convinced Preston does by this short passage), you can see what re-principling accomplishes. It probes the source of your actions. And by contrast, it shows that very similar actions might proceed from “mere habitual strength of nature” only lightly informed by some Bible passages, “observations and examples.”

Thus far the alpha! As for the omega, the new telos, Preston makes his point more directly:

Again as the spiritual strength has a different beginning, so it has a different end… For as the holiness that is in a Holy Man arises from a higher Well-head, so it leads a man to a more noble end than the natural strength.

For the end of the spiritual man’s strength is Gods glory, that he may yield better obedience unto God, that he may keep truth with him, and keep in with him that he may have more familiarity with him, and more confidence and boldness in prayer; in a word, that he may be fit for every good work.

But the end of the natural strength, is his own ends, his own profit and pleasure, and his own good. For as the rise of any thing is higher, so the end is higher. As for example: water is lifted upon the top of some Mountain or high place, because it may go further than if it were not. So when a man is strong in the inward man, he is set up higher for another end, and that is to please God, and not himself. (84-85, repunctuated and spelling updated)

There are several things worth noting here: First, Preston helpfully uses the phrase “the holiness that is in a holy man,” which reaffirms that he is talking about something actually residing in a believer and making progress, subject to development and increase. To speak scholastically, we are in the domain of habitual grace, brought about by the grace that makes gracious.

Second, this strength in the inner man does not have to rise absolutely to the level of God’s own strength, nor his holiness to God’s own holiness. How could it? But it does have to correspond appropriately to its source and end; it has to be appropriate, fitting, and becoming. The goal is not some sort of absolute perfection so much as fitness for fellowship, “that he may keep truth with him, and keep in with him” enough to pray to God and work for God.

Third, the higher alpha is what leads to the higher omega. Because spiritual strength starts in God, it tends toward God. The dynamic of its ascent is proportional to the impetus of its descent.

And fourth, although Preston’s long discourse on Eph 3:16 seems at times to be far away from its source text at an extremely high altitude orbit, I want to point out that the principle-and-telos analysis in fact makes remarkable use of resources directly at hand: Paul prays “That he might grant you according to the riches of his glory, that ye may be strengthened by his Spirit in the inner man.” Preston’s book on the strengthening of the inner man employs “by his Spirit” as its principle, and “the riches of his glory” as its telos. Furthermore, there is great value in setting aside some time to mediate on the strengthening of the inner man at the end of Ephesians 3, before turning to Ephesians 4 and its account of how we should “walk worthy of the calling with which we have been called.”

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.