A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

“His Own Son,” that is, “Legitimate, Distinctive, Essential, and Special Sonship”

When he wants to make the ultimate claim about the greatness of God’s love, Paul puts it into the ultimate perspective: He compares it to the greatness of God’s own son. Consider Romans 8:32: “He who did not spare his own Son but gave him up for us all, how will he not also with him graciously give us all things?”

There is a lot happening in this passage, but it all hinges on the word “own.” What does it mean to call Jesus God’s “own” Son? You might paraphrase “his own Son” as “not just any son,” or “not just any kind of son,” or “not one of the various other things that can be called sons of God in an extended sense,” but an actual, factual, connatural son, the kind that belongs to him by nature.

That seems like a lot to get from the little word “own,” but it’s a good unpacking of the way “his own Son” is more emphatic than just saying “his Son.”

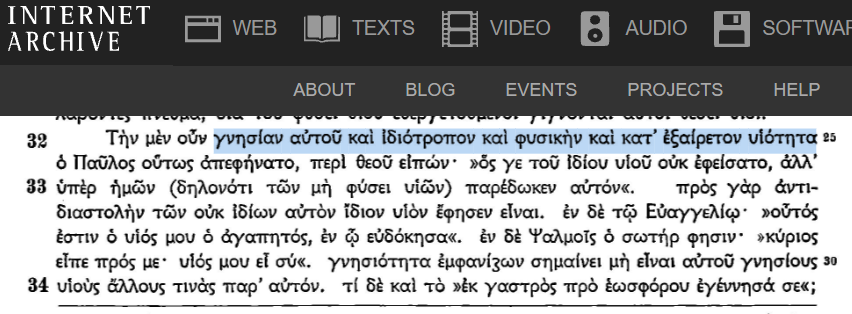

The early church fathers picked up on Paul’s meaning here and amplified it. It’s easy for us to overlook, but for the Greek fathers of the Nicene period, this expression in Rom 8:32 was a deeply meaningful text. Alexander of Alexandria at the very beginning of the Arian controversy gave a kind of expanded paraphrase of “own,” saying that God was making known Jesus’ “legitimate, distinctive essential, and special sonship.”1 [γνησίαν αὐτοῦ καὶ ἰδιότροπον καὶ φυσικὴν καὶ κατ᾽ ἐξαίρετον υἱότητα]. In fact, the power of Rom 8:32 comes from the contrast between that one genuine Son and the ones for whom he died: the one who is Son by nature died for us “who are not sons by nature” [τῶν μὴ φύσει υἱῶν].

I also appreciate how Alexander uses the abstract noun “sonship” here [υἱότητα], to clarify that it is the nature of Sonship that is under discussion. THAT kind of sonship compared to THIS kind of sonship. The point of Paul’s gospel proclamation is to relate these two kinds of sonship, but the relation is only possible because of the infinite qualitative distinction between them. It’s greater than “all things,” and is the only possible measure of the love of God in Christ.

_____________________________

1This is John Behr’s translation in The Nicene Faith, Part 1 (St. Vladimir’s, 2004), p. 126. I think ‘genuine’ would be a clearer way of rendering γνησίαν, especially since the opposite of ‘legitimate son’ would be ‘illegitimate son,’ which has distracting connotations. For Alexander, the opposite of a genuine Son is one who is not son by nature.

The Alexander text is in Urkunden zur Geschichte des Arianischen Streites, Athanasius Werke, Vol. 3, Pt 1, In edited by H. G. Optiz, Berlin: De Gruyter, 1934, at page 24. The key section is free at Internet Archive. I don’t know of an English translation; I only know this text because Behr interacted with it in his 2004 book. More recently Behr has returned to it in his article “The exegetical Dimensions of the Nicene Debate,” International Journal of Philosophy and Theology 86:2–4 (2025), 96–107. If I find other interactions with Alexander’s statements, ancient or modern, I’ll jot them down here.

Note to self, I’d also like to look into how Rom 8:3 says ἑαυτοῦ Υἱὸν and 8:32 says ἰδίου Υἱοῦ; has anybody drawn that out?

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.