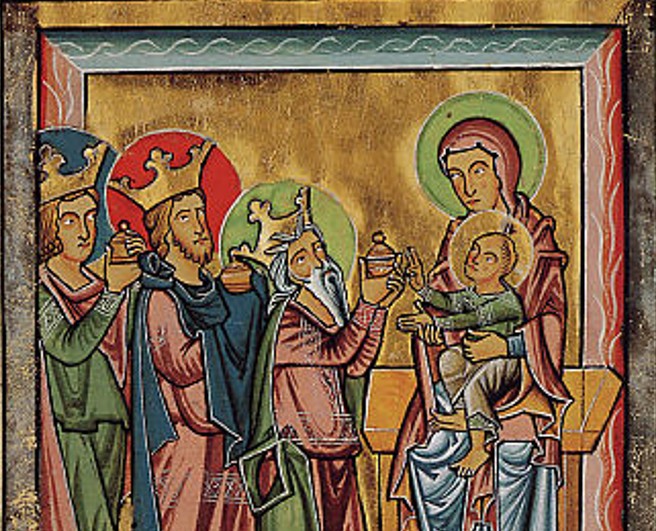

A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

Not Ashamed to Call US Brothers [Magi Sermon]

Here’s video (just below) and a manuscript (below that) of a sermon I preached at my church on Dec 28, 2025. As I explain in the introduction, it was the concluding sermon of our Advent series. I wrote it in some haste and hadn’t planned to post it publicly, but it includes some good theological interpretation of Matthew’s story of the Magi that I wanted to make available. On top of that, I incorporated visual art in a way that might be instructive and even unique. It sounds boastful to say this, but I am more conversant with the history of Christian iconography than you might reasonably expect from someone who in this very sermon makes the point that all tradition is to be judged by scripture alone. I was an art major, after all. And the AV team went the extra mile of showing the pictures in the video nicely, too.

Not Ashamed to Call US Brothers (Matt 2:1-12)

We’re finishing up a set of Christmas sermons under the series title “Not Ashamed to Call Them Brothers,” exploring all the ways the Son of God came to be part of the human family, for us and for our salvation. So we’ve been in the first chapter of the Gospel of Matthew, and it has really been an exploration of Jesus’ family tree, looking at his lineage from all those brothers and sisters and (grandpas and grandmas) in his entire Old Testament genealogy, down to his immediate family of Joseph and of course Mary: And the point has been to spend Advent focusing on the love of God in Christ: that the Son of God was not ashamed to take to himself a whole centuries-long genealogy, and then to call Joseph his father and Mary his mother.

And now on the first Sunday after Christmas, we follow Matthew’s Gospel as it makes a sudden sharp turn from the people Jesus Christ is directly related to, to some strangers from far away. Look at it in the section headings in Matthew: In chapter 1 you’ve got a genealogy, and then the holy family, and then BOOM, chapter 2, Visitors. “Wise men from the east.” Who are these guys? Where did they come from all of a sudden, and why did they interrupt the family Christmas story? Well, we’re going to find out this morning by reading their story and exploring it a little bit.

But even before we get into it, I think you can already tell, just from the flow of Matthew’s Gospel, what the main point is: The Son of God is not ashamed to claim his own ancestors; he’s not ashamed to claim his own parents; but he’s also not ashamed to claim all those who believe in him, and to call them – that is, to call US—brothers and sisters. This final sermon in the series is where we really make the complete jump from them to us, to all of us.

By setting up the story this way, Matthew takes his readers from Jesus’ actual biological relatives to the rest of the world. Matthew lifts our eyes from the particular family tree to the forest the tree is in; or we might even say, he lifts our eyes to the stars above. Look at the art on the front of your program: there’s the tree, and above it is the star. It’s the star of Bethlehem; and it’s the star on top of the Christmas tree; and it’s the star of US.

Let’s get into the story:

Matthew Chapter 2, verse 1: Now after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of Herod the king, behold, wise men from the east came to Jerusalem, 2 saying, “Where is he who has been born king of the Jews? For we saw his star when it rose and have come to worship him.” 3 When Herod the king heard this, he was troubled, and all Jerusalem with him; 4 and assembling all the chief priests and scribes of the people, he inquired of them where the Christ was to be born. 5 They told him, “In Bethlehem of Judea, for so it is written by the prophet:

6 “‘And you, O Bethlehem, in the land of Judah,

are by no means least among the rulers of Judah;

for from you shall come a ruler

who will shepherd my people Israel.’”7 Then Herod summoned the wise men secretly and ascertained from them what time the star had appeared. 8 And he sent them to Bethlehem, saying, “Go and search diligently for the child, and when you have found him, bring me word, that I too may come and worship him.” 9 After listening to the king, they went on their way. And behold, the star that they had seen when it rose went before them until it came to rest over the place where the child was. 10 When they saw the star, they rejoiced exceedingly with great joy. 11 And going into the house, they saw the child with Mary his mother, and they fell down and worshiped him. Then, opening their treasures, they offered him gifts, gold and frankincense and myrrh. 12 And being warned in a dream not to return to Herod, they departed to their own country by another way.

You’ve heard that story before, but WOW, what a great story. It’s got everything. This story of the visitors from the East is only told by Matthew. It’s not in Luke or the other Gospels, so we can’t cross-reference it to other ways of telling it to see if there are any other juicy little details provided, or different ways of saying things. Everything we know, we know from Matthew, from the 12 verses I just read. And he gets it done in about 300 words.

One commentator says, “The story of… the Magi is told by St. Matthew, in language of which the brevity constitutes the chief difficulty.” (Alfred Edersheim) Did you catch that? The main problem about the story is that it’s so short: it makes us wonder all kinds of things, and wish we had all kinds of details. People have always wondered all kinds of things about this story.

(By the way, here’s a fourth-century carving of the visitors coming to see Jesus; you can see them carrying their gifts and pointing to the star. I’m going to show you several pictures of the visitors this morning, and this is the oldest one I’ll show you.)

Here’s one thing we wonder about: What’s the right thing to call these visitors? I just read from the ESV translation, which calls them “wise men.” That’s pretty much the oldest English tradition of what to call them: William Tyndale used it in 1534; the King James Version in 1611; and the ESV is sticking to that good old tradition.

But the actual Greek word used here is magoi, or we could pronounce it magi. Now it doesn’t do much good to say that the Greek word for magi is magi… that’s not really translating, is it? It’s just putting the same word there instead of trying to find an English word. But some modern Bible translations have decided to go that route, so if you’re reading the NIV or the NAS, you’ll see that “Magi came from the East.” The idea there is that we don’t really have an English word for Magi, so we just use the Greek word, which is actually borrowed from an even older Persian word. It’s kind of like if I asked you what’s the English word for Rabbi, you’d have to decide whether to say “teacher,” which is what Rabbi means, or just say Rabbi, since the English word for Rabbi is Rabbi, in the sense of a specific kind of Jewish teacher. Just like that, the English word for Magi is Magi, if you mean not just any wise man, but a very specific kind of wise man… who came from the East, following a star, to find the king of the Jews. That’s the kind in our story, the Magi kind of wise men.

So no mystery there about what to call the visitors; take your pick. But we do wonder all kinds of other things, like how many of them there were. The fact is, it doesn’t say. Right? We just read the story, and Matthew did not give us a number. So people wondered about that, and as they wondered, they made up some ideas. Early on, some people guessed there were 12 Magi, and then later some people guessed there were hundreds of them, with all their servants and bodyguards and diplomats, for a total travelling part of thousands. If that was the case, no wonder Herod and the people of Jerusalem were worried about their arrival!

But most people have guessed that there were three of them, and you probably know why: Because while Matthew doesn’t tell us how many Magi there were, he does tell us exactly three kinds of gifts they brought: Gold, Frankincense, and Myrrh (verse 11). So, at one gift per wise man, we’d get the traditional three Magi. And that sets up an old tradition of thinking about each one of the three gifts as symbolizing something about Jesus: Gold because he is the King, Frankincense because he will be spiritually the priest who burns incense or because he is the God to whom incense is burned, and Myrrh because he is the sacrifice, and myrrh was a spice used in burial. You may know that in the song “We Three Kings of Orient Are,” each one of the Magi sings a verse about the gift they bring, and then they sing together at the end, as they join in unison to sing “Glorious now behold him arise; King and God and sacrifice: Alleluia, Alleluia.” It’s great stuff! You can see that Christians love this story, and it’s a story that makes us wonder about all kinds of things that aren’t in the text, but it also makes us pay super close attention to every single word that is in the text: you can read through the whole Bible looking for what Gold means, what Frankincense means, and what Myrrh means, and then bring all that meaning back to this brief story, and make beautiful songs and beautiful poetry and beautiful art about it, because it’s all about who Jesus is.

But remember: Matthew doesn’t say three Magi. It’s a convenient, no-harm, no-foul, why-not, kind of guess, and it supports a tradition that can help us explore the variety of special gifts they brought, which Matthew does itemize. Three gifts is text: Three Magi is commentary, in the maybe zone.

But another thing people have wondered about is, what were their names? By this time I hope you know the right answer: Matthew. Doesn’t. Say. So we don’t know. But not everybody can stand that kind of answer down through the centuries, so a long time ago, somebody invented names for the three Magi: Can you see them in this sixth-century mosaic from Italy? It says it right above them: Balthasar, Melchior, and Kaspar. Those are cool names. Do we have any Balthasars in the church with us this morning? No? Kaspar? No?

Where in the world did these names come from? Historians believe they were derived through a sociological process known as pure fabrication. They were made up! Somebody couldn’t stand not knowing, so they pretended they knew. This is actually bad, but it actually happens a lot: “Through the ages, readers of the Bible have felt the need to identify some of these anonymous figures… and so names (at times more than one) have been provided for many of these unidentified persons.” [Bruce Metzger; all the info that follows in this section is from a Metzger article described here.] In fact, if you think of any character from any Bible story whose name is not given in the text, I can almost guarantee that at some point, somebody somewhere in the history of the church, made up a name.

Think about Noah’s wife. You can only call her Mrs. Noah for so long before you start wishing you had her name… and I kid you not, over 100 different names for Mrs. Noah have been invented. The most popular one is… Emzara. Why? Nobody knows; they made it up.

Potiphar’s wife? Zuleika.

Jephthah’s daughter? Seila.

Job’s wife? Sitis. And his second wife, Dinah.

The witch of Endor? Sedeikla.

It’s easy to see how this starts. Once when we were preaching through Acts, I got to tell the story of the Philippian jailer who imprisoned Paul and Silas. Part way through the sermon, I got tired of calling him “the Philippian jailer,” (seven syllables!) so I started calling him Phil. It made the story go better, and it also started making me kind of feel like I knew the guy. No harm no foul, I hope, but I’d be scandalized if anybody went away thinking the Bible told us the name of the Philippian jailer! I don’t want to add any words to Scripture.

Think about Noah’s wife. You can only call her Mrs. Noah for so long before you start wishing you had her name… and I kid you not, over 100 different names for Mrs. Noah have been invented. The most popular one is… Emzara. Why? Nobody knows; they made it up.

Potiphar’s wife? Zuleika.

Jephthah’s daughter? Seila.

Job’s wife? Sitis. And his second wife, Dinah.

The witch of Endor? Sedeikla.

It’s easy to see how this starts. Once when we were preaching through Acts, I got to tell the story of the Philippian jailer who imprisoned Paul and Silas. Part way through the sermon, I got tired of calling him “the Philippian jailer,” (seven syllables!) so I started calling him Phil. It made the story go better, and it also started making me kind of feel like I knew the guy. No harm no foul, I hope, but I’d be scandalized if anybody went away thinking the Bible told us the name of the Philippian jailer! I don’t want to add any words to Scripture.

But this names-for-the-nameless tendency can really get out of hand. In one Christmas tradition, we’re told that the angels appeared to exactly seven shepherds, and the shepherds’ names were Asher, Barshabba, Justus, Jose, Joseph, Nicodemus, and Zebulan. It’s really pretty ridiculous! What’s next, the names of the sheep? When Jesus sends out 70 disciples, one medieval book provides a list of all their names. The thieves on the cross? Dysmas and Gestas. The centurion? Longinus.

Compared to this, the traditional three Magi names seem pretty restrained and harmless: Balthasar, Melchior, and Kaspar. But they’re equally made up, and another ancient source names the Magi Basanter, Hor, and Karsudan. And another source sticks to the idea that there were 12 magi, and provides all of their names, plus their fathers! So we are just not on solid ground here. What’s solid ground? The text, the text, the text.

I want to make three minor points here before we actually get to the main point of the Magi story:

First, it’s okay to wonder about things; the Bible is written in a way that it awakens our minds and arouses our wonder and even engages our imaginations and senses. Bring it all to God, since and dance and use your creativity. But it is not okay to lie, it’s not okay to pretend you know more than you know, or to make things up and treat them like they are in the Bible. There’s a difference between the imaginative and the imaginary, between hallelujahs and hallucinations. Wondering is welcome.

Second, a protestant point: Sola Scriptura. The things we know from scripture belong in a special category of revealed truth, absolute truth, God’s own word. Everything else has to be judged by what’s in scripture. Everything else miiiight be helpful, but needs to be evaluated by what? By scripture alone. Christmas is actually a great time to quiz ourselves on this, because during this season we hear all these songs and see all these pictures and we’re told all these stories and we get all this commentary about the birth of Jesus, and … some of the things we hear are true and some of it’s made up. Your mind can just get full of all kinds of input from who knows where, and good stuff along with bad stuff along with weird stuff, and it’s up to you to think critically and sort through it. How can we tell the difference? By Scripture alone. What saith the word of God? Run everything through the Bible grid. Text is text, and commentary is commentary. Sola Scriptura.

Third, can I talk about Christmas clutter? I’m not talking about anybody’s housekeeping, which I know might be a sensitive subject this week. By clutter, I mean all the stuff that builds up as we celebrate the coming of Jesus Christ. Now some of it’s bad and junky, and we just talked about that. But a lot of it’s fine and dandy, lovely and decorative, celebratory like a lavish party, but it’s just that there’s a lot of it. And when that clutter builds up, it can be distracting, and it can obstruct our view of the main thing. Here’s a glorious example: this is a sculpture in Rome by Bernini, with a throne surrounded by twisty columns and a golden cloudburst and beams of light and shafts of gold and a descending dove and a bunch of writhing angels blowing trumpets and… wow. This is great art, y’all. Sublime and impressive. But it’s also such a crowded spectacle that it’s hard to remember what it’s there for, what’ the point. I think Bernini’s point is something about Christian teaching, but it’s really in danger of getting lost in the glitz.

Here’s another example: This is an altar wall in a style called Ultrabaroque, and just like Bernini’s sculpture, it’s impressive, it’s got gold, it’s got angels, it’s got… well, it’s got a lot of a lot, doesn’t it? If you’re like me, you’ve got to responses at the same time: on the one hand wow, but on the other hand, eww. I can’t breathe. It’s almost impossible to say what we’re supposed to focus on here, or what actual content is actually being depicted. “Are you in there, baby Jesus?” Somewhere in the undulating revelry and riot of golden filigrees and saints and traditional forms? Friends, this third point I’m making is also a Protestant point, and it’s not about artistic styles or taste. It’s about clutter. There is such a thing as spiritual clutter. It is possible to let details and habits and pious traditions pile up in our lives to such an extent that we lose our ability to focus on the main thing. I’m not even talking about sin, I’m talking about the buildup of barnacles and good things that keep us distracted from focusing on Jesus Christ. Spiritual clutter is stuff that starts out as good ideas but just builds up and up and up until it distracts. As we turn the corner to the new year, and we admit that it’s time to undecorate and get back to normal life, I hope you’ve really been able to celebrate the coming of Christ. And I hope you can also find ways to unclutter and start the new year serious, sober, and singleminded about worshipping Jesus. Like the Magi, which brings us back to the main thing.

What’s the main thing? Gentiles worshipping Jesus. This is the US part.

Whoever these Magi are, they are not from around these parts; they are not Jews from Jerusalem, they are from somewhere far away, and as Matthew tells his story of Jesus as the messiah and king, he goes out of his way to drop these 12 verses in to let us know that Gentiles are going to be included. This is Matthew’s way of showing us that the good news of Jesus the Messiah is not just good news for the people of Israel, but for the entire world, for all people, for all kinds of people. [Here’s a set of statues depicting the Magi bringing their gifts; it was made about 1515 and it features everybody dressed the way they would dress in 1515]

The big contrast in this story is between Herod the Magi: Herod ought to understand but doesn’t; the Magi have very little to go on but understand perfectly. Picture Herod and his professional scholars who have the word of God in their hands and know how to read prophecies, and are about six miles from where the action is taking place; versus the Magi who are working with star charts, scraps of information about another nation’s traditions, and barely know enough to go to the capital city and ask for directions, and have to take a massive road trip from the ends of the earth. Herod had everything at his fingertips but twisted it on purpose, while Magi had very shoddy information but made the most of it. So against all odds, here they come from far away, carrying regal gifts and humming “O come let us adore him” as they bow down before the true king.

The way Matthew tells the story, it seems to me it is supposed to remind us of an impressive Old Testament event in which a foreign dignitary came from far away to see the Son of David and learn about him. I’m referring to the story of the Queen of Sheba. Do you remember that story? It’s in I Kings Chapter 10. I’ll read it to you, starting at verse 1: “Now when the queen of Sheba heard of the fame of Solomon concerning the name of the Lord, she came to test him with hard questions. 2 She came to Jerusalem with a very great retinue, with camels bearing spices and very much gold and precious stones.”

[Ah, there’s the giveaway: spices and gold. Sheba, by the way, was a kingdom way down south of Israel in the territory we would now call Yemen. The story goes on:]

And when she came to Solomon, she told him all that was on her mind. 3 And Solomon answered all her questions; there was nothing hidden from the king that he could not explain to her. 4 And when the queen of Sheba had seen all the wisdom of Solomon, the house that he had built, 5 the food of his table, the seating of his officials, and the attendance of his servants, their clothing, his cupbearers, and his burnt offerings that he offered at the house of the Lord, there was no more breath in her. [You are so rich I cannot breathe.] 6 And she said to the king, “The report was true that I heard in my own land of your words and of your wisdom, 7 but I did not believe the reports until I came and my own eyes had seen it. And behold, the half was not told me. Your wisdom and prosperity surpass the report that I heard. 8 Happy are your men! Happy are your servants, who continually stand before you and hear your wisdom! 9 Blessed be the Lord your God, who has delighted in you and set you on the throne of Israel! Because the Lord loved Israel forever, he has made you king, that you may execute justice and righteousness.” 10 Then she gave the king 120 talents of gold, and a very great quantity of spices and precious stones. Never again came such an abundance of spices as these that the queen of Sheba gave to King Solomon. … 13 And King Solomon gave to the queen of Sheba all that she desired, whatever she asked besides what was given her by the bounty of King Solomon. So she turned and went back to her own land with her servants.

Well, you see the similarities here, but you can also see a great reversal: The Queen of Sheba was astonished by the wealth of the Son of David seated on the throne in Jerusalem; the Magi come to an unimpressive baby king in a normal house in Bethlehem. It’s exactly the kind of fulfillment Matthew loves to trace; often Matthew will give us the prophecy formula, “this took place to fulfill what was written in the prophet,” and then quote the prophet. In his case, he just tells the story and does not give us the fulfillment formula. But he could have said “this took place to fill our minds with the vision of fulfillment embedded in the visit of the Queen of Sheba,” or he could have said, “this took place to fulfill the prophecy of Psalm 72:”

8] May he have dominion from sea to sea, and from the River to the ends of the earth! [9] May desert tribes bow down before him, and his enemies lick the dust! [10] May the kings of Tarshish and of the coastlands render him tribute; may the kings of Sheba and Seba bring gifts! [11] May all kings fall down before him, all nations serve him! (ESV)

This prophetic connection, by the way, is probably why we started calling the Magi, or Wise Men, by the honorary title of “Kings.” Here’s a painting from the 1400s where they are wearing fancy crowns and look just like kings from medieval France. European artists LOVED to paint the Magi as European kings. Why? Partly because they were the only kings the artists could picture, but partly because they knew what this story and prophecy meant: This story about the visitors from far away who came to the king of the jews and understood who he was, and gave him gifts and bowed down and worshipped him, meant that all the nations of the world had been called by God to worship the God of Israel. This kind of picture shows the nations of Europe imagining themselves into the Bible story and confessing Jesus as the Christ.

Now maybe you’re thinking the Queen of Sheba used to be very famous but isn’t famous enough now that she automatically springs to mind right away. That’s fine, but from the Old Testament to the new, she was the proverbial figure of a wealthy, faraway, pagan dignitary. Jesus had exactly this story in mind later in Matthew 12 when he was arguing with the Pharisees:

38 Then some of the scribes and Pharisees answered him, saying, “Teacher, we wish to see a sign from you.” 39 But he answered them, “An evil and adulterous generation seeks for a sign…” 42 The queen of the South will rise up at the judgment with this generation and condemn it, for she came from the ends of the earth to hear the wisdom of Solomon, and behold, something greater than Solomon is here.

Here they are again, Kingy as ever, European as ever, coming from the ends of the earth and bringing gifts to the one who is greater than Solomon.

There are hundreds of paintings like this, and eventually the artists start making the three Magi Kings represent three different ages: young, old, and very old. And somehow the oldest one is always in front, dressed best, most dignified, and always bowing down the lowest in front of baby Jesus.

I think they’re young, old, and very old to try to show that they represent all ages of people, as a kind of visual way to show that everybody who comes to Jesus can worship him, no matter what age. Again, Christian readers trying to do the work of imagining themselves into the story, because they have faith.

And later in these European paintings, there’s even a tradition in which people start thinking bigger about what it means that Jesus is the savior not just of Jewish people and not just of European people but of people from every tribe and tongue and nation. So the three kings undergo another artistic transformation, where they’re not only young, old, and oldest, but become white, black, and middle eastern or even Asian.

If you look at a lot of paintings of the visit of the Magi, keep an eye out for this: all ages, and some attempt at painting all nations or at least enough symbolic diversity to make the point: What’s the point? It’s the main point of the passage, and of this sermon: that Jesus Christ was not ashamed to call US, all of us, all kinds of us, his brothers and sisters.

Jesus makes this point better than the painters – surprise surprise!—later in Matthew. In Matt 12:46, it says, “While he was still speaking to the people, behold, his mother and his brothers stood outside, asking to speak to him. 48 But he replied to the man who told him, “Who is my mother, and who are my brothers?” 49 And stretching out his hand toward his disciples, he said, “Here are my mother and my brothers! For whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister and mother.”

He is not ashamed to call us his family; he does the work of making us his family.

In Matthew 8, when he heals the servant of a centurion, Jesus says of this Gentile who has faith in him: “Truly, I tell you, with no one in Israel have I found such faith. I tell you, many will come from east and west and recline at table with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven, while the sons of the kingdom will be thrown into the outer darkness. In that place there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.” (Matt 8:11)

We started out by looking closely at how Matthew begins his Gospel: he begins with a genealogy, and then this powerful little 12-verse story about Gentiles coming from far away to worship the one born king of the Jews. And then the Magi go away and we don’t hear from them again in Matthew or in the whole Bible. Was it just an interesting little episode? No, it was Matthew’s way of setting us up for the main point, and we know that because he comes back to it at the end of the Gospel. How does Matthew’s gospel end? Famously, with the Great Commission, where the risen Jesus tells his disciples,

All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. 19 Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, 20 teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age.”

There are the Magi: “disciples of all nations.” At the beginning of Matthew, more or less symbolically, they are already there, coming from the ends of the earth and kneeling down in adoration of the one born King; And at the end of the Gospel, there they are, but with the strange reversal that Jesus’ apostles are going out to them: out to Europe and Yemen, to Arabia and America, to Africa and Asia, to make disciples of the one to whom all authority in heaven and on earth has been given. At the beginning of the Gospel, he was already born king; at the end, he has died for our sins, risen for our salvation, and stands declaring his authority in person. At the beginning he held patiently still and the nations came to him; at the end he commissions his church to go to the nations. Matthew loves to wrap up his story this way: At the beginning in chapter 1 verse 23 an angel told Joseph that this child shall be called “Immanuel, which means God with us. At the end, in chapter 28:20, Jesus tells us in his own voice: I am with you always. “God with us/I am with you.” All of you, all kinds of you, all nations. I am not ashamed to call you brothers and sisters.

Well, we certainly haven’t answered every question that this story has raised for us. We’ve marvelled at the Magi, and wondered with the wise men, and focused our attention where it needs to be focused, on the fact that Jesus Christ is Lord of all and calls people from every nation to be his disciples. But we’re out of time for wondering everything we could wonder about the -star of wonder, star of light, star with royal beauty bright, westward leading, still proceeding, etc. Maybe we can take another shot at it next year. The Magi followed that star and let it point them to the true king.

Do you remember way back in Genesis, God took Abraham outside to see the night sky and said to him, “Look toward heaven, and number the stars, if you are able to number them.” Then he said to him, “So shall your offspring be.” 6 And Abraham believed the Lord, and he counted it to him as righteousness. There’s a lot we don’t know for sure about the Star of Bethlehem –what was it, where did it go, etc– but we know it shines in the firmament that Father Abraham saw when he believed in God, and was justified by faith, and became the father of many nations.

Amen. [Closing prayer]

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.