A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

Sermon: Learn a Lesson from a Dirty Scoundrel (Luke16)

[Preached Sunday, February 5 at Grace Evangelical Free Church of La Mirada]

Learn A Lesson From A Dirty Scoundrel (Fred Sanders).mov from Grace EV Free on Vimeo.

Hi friends. So I entitled this sermon, “Learn a Lesson from a Dirty Scoundrel,” and then it occurred to me that as I’m walking up here, you might be thinking, “Aha, so this must be that dirty scoundrel we’re going to learn the lesson from!” Well, that at least wasn’t the point of the title.

The point of the title is this: We’re going to explore this parable this morning, and I just want you to remember very clearly that the main character is a bad dude. He is a rascal. That’s not just my spin on it, or just my interpretation, it’s what Jesus explicitly says in the text: Just glance at Luke 16, verse 8 for a second: “The master commended the dishonest manager for his shrewdness.” There it is, he’s dishonest; unrighteous; unjust. So that’s not an open question, it’s settled. Our job this morning is to learn the lesson Jesus is teaching us, by understanding what is going on with this dishonest manager.

The Parable of the Dishonest Manager

Let’s get right into it: Luke 16:1

16 He also said to the disciples, “There was–

Wait wait, can I stop here for a second? I just want to point out that Jesus is talking to the disciples. Since 15:1, he’s been talking to a mixed group that includes his disciples, a bunch of tax collectors and sinners who are drawn to him, and a bunch of hostile scribes and Pharisees who are offended by him. But here he’s talking to the disciples. This parable has a lesson for Jesus’ followers. If you’re a disciple of Jesus, this is instruction for you. Everybody else can hear him, too: down in 16 verse 14 it says the Pharisees heard this and responded by ridiculing him. But those are hecklers, and he’ll deal with them next week. This parable here has in it a lesson for those who follow Jesus and learn from him. So “today if you hear his voice, don’t harden your heart.”

16 He also said to the disciples, “There was a rich man who had a manager,

and charges were brought to him that this man was wasting his possessions.

That is, the manager was mismanaging the master’s business and squandering his goods.

2 And he called him and said to him,

‘What is this that I hear about you?

Turn in the account of your management, for you can no longer be manager.’

Modern paraphrase: You’re about to be fired, and probably more than fired. Your job is done, and I want to see all the receipts and paper trail, because there is going to be a complete audit of everything you’ve had your dirty little fingers in. As soon as you transfer all those records and files over to me, security will escort you from the building. Now maybe this happened by email or something (the text is not clear), because the manager had just a little bit of time to think, and hatch a scheme and carry it out:

3 And the manager said to himself,

‘What shall I do, since my master is taking the management away from me?

I am not strong enough to dig, and I am ashamed to beg.

4 I have decided what to do, so that when I am removed from management,

people may receive me into their houses.’

5 So, summoning his master’s debtors one by one, he said to the first,

‘How much do you owe my master?’

6 He said, ‘A hundred measures of oil.’

He said to him, ‘Take your bill, and sit down quickly and write fifty.’

Okay, just a quick word about this transaction: A hundred measures of oil is something like 900 gallons. If you’re trying to picture it, it’s something like, fill up your entire bathtub 25 times. Or fill your gas tank 50 or 60 times, depending on your gas tank. Just a rough estimate here, to picture it: 900 gallons is nowhere near enough to fill up a swimming pool, but it’s 5 or 6 hot tubs. You can’t move this around in your car or keep it in your apartment; you need serious shelf space to store it and a supply chain to move it. My point is, this is not just some domestic quantity, the manager is negotiating the financing of a business transaction, and the people involved are moving shipments of product.

That’s the scale. And now the proportion is, HALF. Our guy the manager, by the authority still vested in him, cuts this debt by 50%. Gets the paperwork, does a quick refi, baddabing, baddaboom, and suddenly Simeon the oil merchant walks away owing only 450 gallons instead of 900. Thanks, manager!

7 Then he said to another, ‘And how much do you owe?’

He said, ‘A hundred measures of wheat.’

He said to him, ‘Take your bill, and write eighty.’

Now Pause here: That’s kind of the end of the story. At least it’s the last transaction we’re told about, and obviously we’re supposed to fill in the rest of them from our imagination. What I mean is, it’s not likely that the manager summoned only these two debtors: Jesus just sketches out the first two and trusts us to extrapolate from there. In a story like this, the kind of rich man who’s got business deals with 900 gallons of oil and this semi-truck load of wheat is the kind of guy who has plenty of other deals going on, but there’s no need to belabor the point. Each deal’s a different volume and a different percentage. What we’re supposed to track is the manager’s basic move, and we see it here: intervene to reduce the debt, earn the gratitude of the debtor, and then wait for the axe to fall.

So in that sense, the story’s over and there’s nothing else left to narrate except the master’s reaction: But what a reaction.

Verse 8: The master commended the dishonest manager for his shrewdness.

He commended him. But you know what kind of commendation this was: it was a slow clap.

Followed by a finger wag.

This was a “you sly dog, you got me” kind of a commendation.

“You rascal, you. I see what you did there.”

Son of a gun. I extend to you my grudging admiration in spite of my own best interests. I must admit, I did not see that one coming.

Now the story really does stop here, and Jesus goes on to comment on it. So we don’t know what would have happened next with these characters, and we’re left with all kinds of detail questions, like

Did the master go ahead and fire the manager?

Did he try to take legal action?

Did the manager go on to get support from the people whose accounts he’d fixed?

Don’t ask. None of that stuff matters for the point of the story, because all Jesus was after was that one plot twist: How money-manager-man, under pressure, came up with a clever idea for saving his own skin.

So focus on that scoundrel’s shrewd move, and his boss’s response to it. Let’s ask why Jesus sets it before us as something we can learn from. Luke 16:8:

For the sons of this world are more shrewd in dealing with their own generation than the sons of light. 9 And I tell you, make friends for yourselves by means of unrighteous wealth, so that when it fails they may receive you into the eternal dwellings.

10 “One who is faithful in a very little is also faithful in much, and one who is dishonest in a very little is also dishonest in much. 11 If then you have not been faithful in the unrighteous wealth, who will entrust to you the true riches? 12 And if you have not been faithful in that which is another’s, who will give you that which is your own? 13 No servant can serve two masters, for either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and money.”

Well, that’s the explanation. But now for the explanation of the explanation.

I think there are three keys to understanding Jesus’ lesson about the dishonest manager.

1. This Temporary Economy, 2. The Virtue of Shrewdness, and 3. The Danger of Mammon

1. This Temporary Economy

The first key to understanding this parable is the way it dramatically portrays what it’s like to live in a financial system that is all just about to come to a screeching halt, at least for you. The manager’s moment of discovery is when he recognizes that he exists in a temporary economy.

He has apparently been going along for some time as a successful businessman, living His Best Life Now, and putting it on the company expense account. When charges are brought against him that he’s been wasting his master’s possessions, he doesn’t say, “No I haven’t!” He doesn’t start pulling together the evidence that will clear him of the charges. He immediately behaves exactly like somebody who knows he’s been caught with his hand in the cookie jar. And then the story takes us inside his thought life and lets us overhear exactly what he’s thinking:

‘What shall I do, since my master is taking the management away from me?

I am not strong enough to dig, and I am ashamed to beg.

AHA! I KNOW!

I have decided what to do, so that when I am removed from management,

people may receive me into their houses.’

Up until now, he has been living with blinders on, just keeping his eyes on what he can see, what he can manage, who owes how much for corn and oil and stuff. He thinks he’s got a rich, full life and is living large, but he’s been ignoring the bigger picture. He’s actually been spending all his days confined within an artificial and limited system. He knows how to work the system! He’s definitely winning the system. But it’s all in here. All the exchanges, all the interest rates, all the receipts and deadlines, and the relationships and the networking, and the projects and plans… they’re all inside here.

And guess what? He’s about to be on the outside. Because this alarm comes resounding through his little managed world:

“Turn in the account of your management, for you can no longer be manager.”

Or even scarier in the King James Version,

“Give an account of thy stewardship; for thou mayest be no longer steward.”

If this sounds like judgment day, it’s because it’s like judgement day. We are all spending our lives doing business inside of a limited and temporary economy, and the day will come when the one true master, God almighty, will call us to account. Everything we’re doing business with belongs not finally to us, but to the master, and we are all just managers of it, or stewards. One day we must give an account of our stewardship.

Did you notice in Luke 16:9, Jesus said, “make friends for yourselves by means of unrighteous wealth, so that when it fails, WHEN IT FAILS, they may receive you into the eternal dwellings.” He did not say “if it fails,” or “just in case it happens to fail.” It’s not a question of if your earthly resources will run out. The sands are slipping through the hourglass and they will run out. The voice of the master warns us to have a plan for “when it fails,” because we are doing business in a temporary economy and need to plan for the real one, eternity.

Imagine the foolishness of thinking this system is the whole story, and that what we do with this money is the comprehensive reality of value. It’s like winning at Monopoly and thinking you’re winning for reals.

Actually, it’s exactly like that. Here, I brought a board, for a parable about the parable. Imagine being the boss of Monopoly and really just winning like crazy. Just sweeping the whole board, getting all the utilities, putting up hotels, and piling up those sweet goldenrod $500 bills. Anybody ever really just dominate a Monopoly game? Oh, the sheer power of it! Don’t mess with me! I can buy and sell people like you. I have Boardwalk and Park Place with maxxed out hotels! I have money to burn; I don’t even keep track of it anymore. I am a real estate mogul, a land developer who owns the seaboard! In one more round, I will have more money than the bank! Mwahahaha!

But then the game’s over, you gather up the pieces, put the board back in the box, and put the lid on the box. That’s it. The whole thing was a temporary economy. Don’t go flashing your orange $500 bills out here in the real world; those belong back in the box, the only place they have any value. They have no meaning outside of it. You were a millionaire in there, but you monopoly money’s no good out here.

But imagine this: If only there were some way to spend monopoly money inside the game in such a way that you got actually rich in the actual world. What if there were some way to make your real estate deals in Monopoly that actually made a difference in California? Well there’s not. Okay, aside, the Monooly brand is currently enjoying a mini-comeback as a kind of lottery ticket or scratch-off or something. So still not quite the real world. But never mind that, here’s the board game parable: Have you ever played Monopoly with somebody who started being suspiciously extra nice to the other players, selling them properties they wanted, trading with them in ways that were disproportionately advantageous to their opponents, to their own loss? You know what’s going on: they’ve usually decided the game’s a dead loss and they’d rather do somebody a Monopoly favor in hopes that they’ll get a real-world favor in return. So when the box closes up, Mom makes your favorite cookies because you traded her for Marvin Gardens so she could beat Dad. You converted worthless paper money into cookies.

If you’re playing against this person, for a while, you wonder how anybody could part with Marvin Gardens so cheap, and then you realize you’ve been played. “You dirty rat…you weren’t playing Monopoly at all. You were playing meta-monopoly for real-world results.” Slow clap. Grudging admiration.

That’s what’s happening in Jesus’ parable. The dishonest manager finds out there’s another world out there that he is about to be ejected into, so he stops playing the manager game, and starts playing the “I need to make some friends in the outer world” game. He surveys his options and doesn’t like them: when I get kicked out, I’m either going to be a beggar or have to do hard physical ditch-digging labor I’m not used to. I need friends who will support me.

What is your plan for coming to terms with the end of your temporary economy? In Matthew 6, Jesus says,

“Do not lay up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy and where thieves break in and steal, but lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust destroys and where thieves do not break in and steal. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.”

Nothing is safe down here. The only things you can really save are things you can put in God’s safekeeping.

2 Peter 3:10 “But the day of the Lord will come like a thief, and then the heavens will pass away with a roar, and the heavenly bodies will be burned up and dissolved, and the earth and the works that are done on it will be exposed. Since all these things are thus to be dissolved, what sort of people ought you to be? in lives of holiness and godliness…”

Learn a lesson from the dishonest manager, and make a plan for the next life, “since all these things are to be dissolved.”

Now this is a parable for disciples. And as Jesus tells it to his disciples, he is on his way to Jerusalem to put in place the only real plan for how any of us can ultimately stand before God and be justified in the day of reckoning. It means him dying on the cross to atone for our sin, and rising from the dead to be our everlasting savior. The news that judgment day is coming is not good news all by itself, but the news that Jesus offers salvation to those who believe in him is the good news itself. This parable can’t do everything, but Jesus can. This parable presupposes that the person telling it, Jesus, is opening up the way of salvation by grace through faith, and that those disciples who will follow Jesus will do so by trusting his promise of salvation and repenting of their sins. That’s why I pointed out that this parable is for disciples. It doesn’t tell you how to get saved; it doesn’t lay out a plan for how you can actually get from this life to the eternal life of heavenly habitations. It instructs saved people how to live in this world as a temporary economy that will someday shut down its own system and then open out onto the world of eternal life.

In fact, Jesus may be especially talking to those among his followers who are recent converts, publicans and tax collectors and money people, who need his instruction in what followers of Jesus should do with their money. And that’ why it leads us to

2. The Virtue of Shrewdness

which is the second key. Look back at verse 8:

The master commended the dishonest manager for his shrewdness. For the sons of this world are more shrewd in dealing with their own generation than the sons of light. 9 And I tell you, make friends for yourselves by means of unrighteous wealth, so that when it fails they may receive you into the eternal dwellings.

Shrewd is a wonderful word. It means wise, but shrewdness is a particularly strategic kind of wisdom. It means resourceful, crafty, cunning, clever. Again, keep the image in mind of this dirty scoundrel who instantly makes and carries out a clever plan. Jesus commends that: the shrewdness, not the dishonesty. Never the dishonesty; if you’re tempted to lie or cheat or steal or manipulate people, don’t imagine for a second that this parable gives you any cover, or that Jesus will approve. Forget it. No slow clap for you.

But the shrewdness: Jesus commends shrewdness in his followers, and laments that worldly people are more shrewd than God’s people. The Lord is my shepherd, and we are the sheep of his hand. But sometimes we hear that sheep aren’t very smart, and we can start to imagine that our shepherd actually prefers dumb sheep. “Hey, dimwitted sheep make good followers.” Naaah. See here the lesson for disciples is that Jesus the good shepherd wants shrewd sheep. Try saying that three times fast! How many shrewd sheep would a good shepherd shear if a good shepherd could shear shrewd sheep?

Switch up the animal imagery here: In Matthew 10 he sends out his disciples and tells them “Be as wise as serpents and harmless as doves.” He wants both: snake smarts and dove innocence. I think most of us instinctively grasp why Jesus desires his people to be as harmless or innocent as doves. But wise as serpents? Shrewd? It sounds weird to us. Is shrewdness a Christian virtue?

Yes. We should muster all the mental cleverness and resourcefulness we can, and make smart plans, and carry them out effectively, as we steward our resources for maximum impact. Take all those verbs that you might associate with bad guys, subtract the badness, and keep the strategic incisiveness: it is a mark of well-developed Christian character for God’s people to scheme and plot and maneuver and design and have an agenda … to bless their neighbors and do good. One commentary I read for this passage summarized it, “God’s children should be shrewd with possessions by being generous.”

You may be hesitant to accept this. You may be thinking that shrewdness is no virtue, or that you don’t want to be characterized as shrewd. Maybe you’d settle for being found faithful. Well, faithful is good: Jesus commends it here (v. 9). But he also commends shrewdness (v. 8). So if you have an opinion about what a disciple should be like, and Jesus has an opinion about what a disciple should be like, and the two of you disagree amongst yourselves about it… well, one of you is wrong. I’ll just leave that there for your consideraiton.

Remember the old bumper sticker that said “commit random acts of kindness?” I saw a lot of those up in Berkeley back in the day. They always slightly bugged me. Don’t get me wrong, I’m pro-kindness. But what’s so great about the random bit? Wouldn’t it be just as good, nay, sustainably better, to carry out a measured program of consistent acts of kindness? An entire systematic scheme of kind acts? Even a well-ordered hierarchy of acts of kindness in which compassionate concern for peoples’ most urgent and obvious needs is juxtaposed with steady attention to their deepest and most spiritually significant needs.

And of course there’s no need to choose; you can sprinkle some random acts in there for seasoning, but surely the shrewd move would be to make a plan and carry it out systematically. Perhaps use a budget. Maybe tithe. Make commitments to financially support strategically placed people who have the training to be maximally effective at administering kindness precisely when and where it is needed most. Pool your resources with other people to make more of a difference than you can do by yourself. Consider longer-term planning for larger acts of kindness made possible through responsible investing in consultation with a licensed financial advisor.

Jesus values shrewdness, and he wants disciples who are maturing in the shrewd use of resources and money. We need to disaggregate shrewdness from the bad company it keeps. The shrewdness is good; the dishonesty is bad.

One of the best sermons ever preached on this parable is John Wesley’s sermon from the 1700s, entitled “The Use of Money.” Wesley said “perhaps all the instructions which are necessary for [the use of money] may be reduced to three plain rules, by the exact observance whereof we may approve ourselves faithful stewards.”

Those three are: Gain all you can. Save all you can. Give all you can.

They have to go together; you don’t get to pick your favorite one or two.

On “gain all you can,” Wesley says “here we may speak like children of the world,” and sound much like them. When there is an opportunity to make more money, pursue it, “by using in your business all the understanding which God has given you… that you may make the best of all that is in your hands.”

Now by “all you can,” Wesley has in mind some definite limits and conditions. And he gets these from all over the Bible: gain all you can without sinning, all you can without compromising your health, all you can without hurting your neighbor in body or soul, all you can without neglecting your family, all you can without becoming so engrossed in business that you stop caring for the life of your soul, and so on. It’s a strict moral code, as we should expect. But within those biblical limits, Wesley really means it: Gain all you can. Go for it.

Second, save all you can. Turning from income to outgo, Wesley says Christian shrewdness about money forbids us from wasting or throwing away our resources. Beware of frittering away money on inflating your lifestyle just for its own sake. Spend wisely, and don’t overspend.

On these first two points, gaining and saving, there is so much to say. I’m trying to apply our passage specifically enough to be helpful, but not to get all the way down to the level of dispensing detailed financial advice. But a big part of wisdom is knowing when you need to borrow somebody else’s wisdom. So if you need to grow in these areas of income and outgo, don’t be ashamed to ask around for advice about the kind of instruction and programs that your brothers and sisters in Christ have found helpful. There is so much to consider, especially for our lives together here in this sort of crazy place called southern California.

And third, most importantly, give all you can. This comes closest to the plain meaning of our parable and Jesus’ own interpretation of it, which encourages the wise use of money with an eye on eternal results. Randomly if you must, but systematically if you can, make it characteristic of your lifestyle to help those who are in need, and to support those who are carrying out good work.

One reason for this is that the life we share as children of God is a shared life in multiple ways, and that it is a sign of health if mutual aid is constantly coursing its way through the body of Christ in various ways. Meal trains, cash grants, emergency relief, anonymous gifts, those mysterious little envelopes that show up in peoples’ mail boxes that you never find out who they were from. (I won’t tell you who, but we’ve had a person in this congregation who gave anonymous gifts to people in need by enlisting others as secret agents to deliver the gifts anonymously. I know at least three people here who acted as those secret agents. ) Two, four, six, eight, money needs to circulate!

And a second reason is that generous giving helps the giver by breaking the spell that money can cast over us. Money constantly tempts us to think we are not just stewards but ultimate owners. Giving some away snaps things back into perspective and helps keep money in its proper place.

3. The Danger of Mammon:

This last bit, about the spell money wants to cast over us, needs some more attention, and it brings me to my third key for understanding Jesus’ lesson in this passage: the danger of mammon.

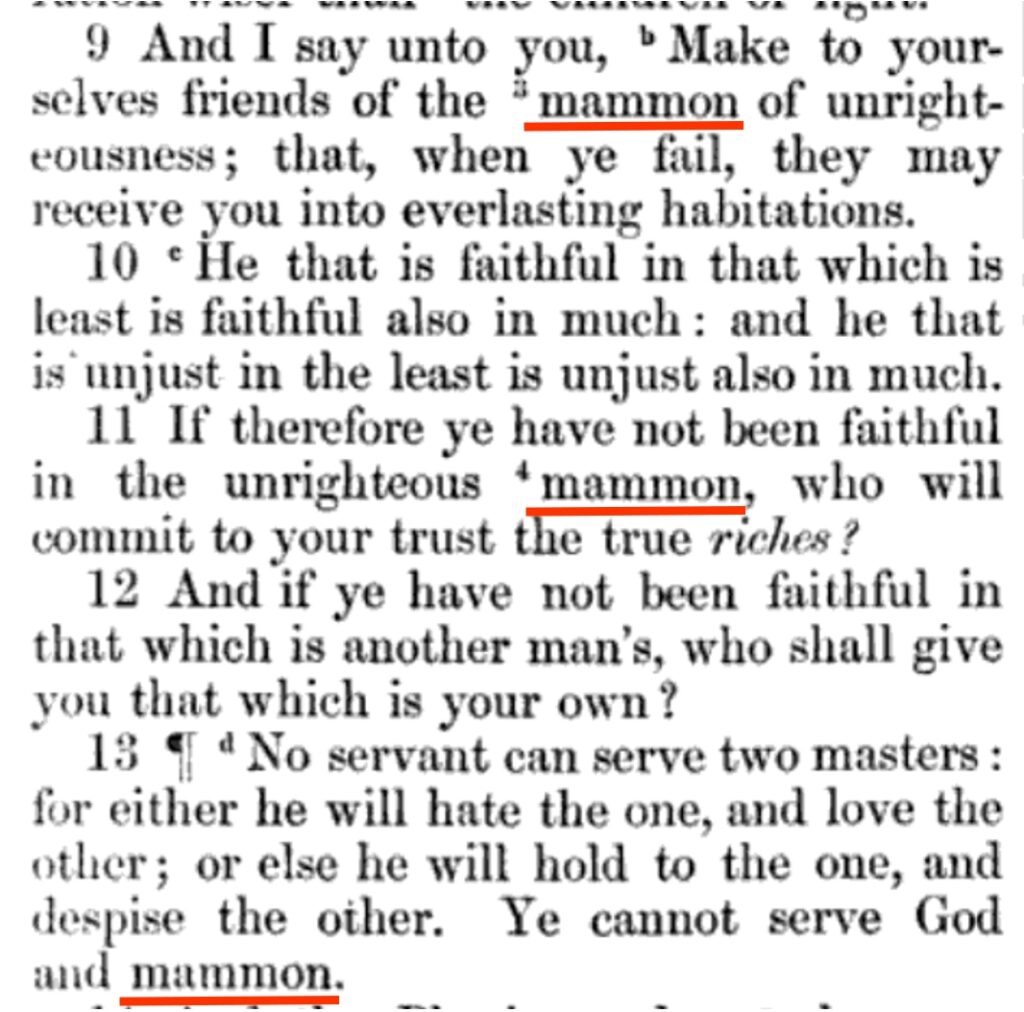

What is mammon? “Mammon” is Jesus’ nickname for money. Let me show it to you in the old King James translation: Here’s Luke 16:9-13 in King James:

You see it three times here in our passage. If you’re reading a more modern translation, you don’t have the word ‘mammon’ in these three places. You probably have the words wealth, wealth, and money. That’s a fine translation; that’s what mammon means. But the New Testament is written in Greek, and in these three spots, Luke doesn’t give us a normal Greek word for money. Instead he reports Jesus as using an Aramaic word. Sometimes when there’s an Aramaic word in the New Testament, our translations just pass it along instead of translating it: think of Amen, Hallelujah, Maranatha, and talitha cumi. That’s what’s going on here, and it’s why I call it Jesus’ nickname for money: it means money, but he uses the weird word Mammon.

This little word only occurs 4 times in the NT: once in Matthew, and the other three times right here in our passage. That’s why I thought it was important for us to look at it. Why does Jesus nickname money?

Well, notice how negative his statements about it are: the first two times he calls it unrighteous mammon. So it’s kind of an insult, or a warning. But on the other hand, in both cases he’s talking about using it well: make friends using the unrighteous mammon; don’t be unfaithful with the unrighteous mammon. So when Jesus describes money, he sometimes puts it down with the nickname mammon, insults it as unrighteous, but then goes on to consider how it can be used well. What’s up with that?

I think what Jesus is teaching us is that money is tricky. It’s just tricky. Think about it: you can’t turn your back on that stuff for a minute. It will run away, or fly away, or depreciate, or inflate, or attract thieves. If you’re not careful about saving all you can, money seems to leak out and spend itself. Where does it go?

And money sometimes starts to exert a mysterious magnetic power that draws our hearts to it even when we know better. Call me your preciousss. It captures our attention and begins to fascinate us; it can infiltrate our thought life and our values system. Money’s mere existence can lure us into attaching a price tag to all sorts of things that shouldn’t have numbers affixed to them.

Why is money so tricky? I’m not sure. It might have something to do with how money is a placeholder; money is not itself a good or a service. It’s a portable, exchangeable placeholder that you can exchange for goods and services. So instead of being some good thing you want—a book, a burrito, a beach vacation– money offers to be anything you want, or everything you want: “hey baby, let me be your book, burrito, or beach vacation.” It’s the portable power to have whatever you want. That makes it pretty potent. It’s almost as if it’s haunted somehow. It’s in your possession, but it would prefer to possess you. You want to spend money, but money wants to spend you. But on the other hand, you can also definitely use it to do good, and you should. I stand with Wesley: Gain all you can, save all you can, and give all you can. In fact, that kind of offense is the best defense.

But also, I think money should always make us just a little bit uneasy… it is a controlled substance. And I think this is what’s going on when Jesus calls it Mammon, and attaches the word “unrighteous” to it. He’s kind of giving it the side-eye even as he’s giving instructions in how to use it. Jesus knows that money is tricky, and he wants us to be learn to be counter-tricky; shrewd, wise, and clever in how we handle money. You can’t just straightforwardly use it; “would that it were so simple.” You need to learn how to use it while it’s trying to use you the whole time.

Mammon, Jesus calls it. Mammon. The word may come from the same root as “amen.” It may have that root idea of trustworthiness. If that’s right, then Mammon suggests not just treasure, but treasure that you trust. And if Mammon has your trust, then once again we’re crossing over into a weird way of talking, where we personify Money: money does this, money does that, money wants something, money has plans. In Money I trust. I trust you, O Money. The old strategy of leaving the word Mammon in our English bibles sort of makes it stand out as if it were personified: “You cannot serve two masters; you cannot serve God and Mammon.”

That’s the trick: Money wants to compete with God for our trust and loyalty. We must repeatedly , decisively, strategically, choose God instead of it, and over it.

In Martin Luther’s Large Catechism, he explains the commandment, “You are to have no other gods” by paraphrasing it: “That is, you are to regard me alone as your God.” And then he poses the question, “What does this mean, and how is it to be understood? What does “to have a god” mean, or what is God?” After all, there is only one true God, so what does ‘have no other gods’ mean? Here is the answer:

A “god” is the term for that to which we are to look for all good and in which we are to find refuge in all need. Therefore, to have a god is nothing else than to trust and believe in that one with your whole heart. …It is the trust and faith of the heart alone that make both God and an idol. If your faith and trust are right, then your God is the true one. Conversely, where your trust is false and wrong, there you do not have the true God. For these two belong together, faith and God. Anything on which your heart relies and depends, I say, that is really your God.

“Anything on which your heart relies and depends, I say, that is really your God.”

The stakes are high here. In Phil 3:19, Paul talks about people “whose god is their belly.” Elsewhere he says that Covetousness is idolatry. You see how these things can sneak into your actual theology, and substitute themselves into the very place of God.

Mammon is the kind of Treasure in which you are tempted to trust. Don’t do it. You know what would be a good idea? To take every piece of money and write on it, “Don’t trust me.” Hey, as it turns out, some of my money actually says right on there, “in God we trust.” That is a pretty good reminder. Mammon wants to be your god. Don’t let him. Outsmart him. Be shrewd.

When you work for money, or with money where is your trust? How do you know?

Are you gaining all you can, saving all you can, and giving all you can?

Pray with me:

God, we want to serve you, and not Mammon. Give us your gifts of strength, steadiness, and shrewdness in our use of money. Lord Jesus, the scoundrel in your parable turned his attention from a temporary economy to a bigger world, and shattered the hold that money had on him. Give us power to do the same. In Jesus name we pray, Amen.

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.