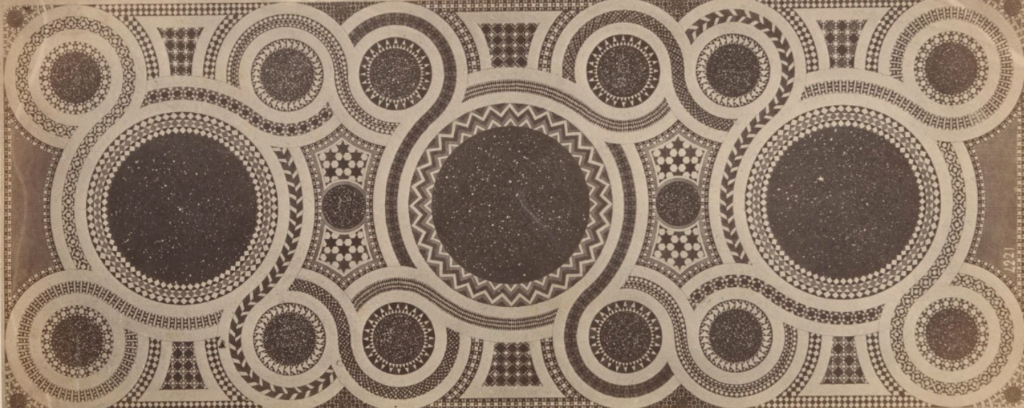

A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

Three Things Are Too Difficult For Me

I hope it’s obvious that I freely and confidently affirm and teach the doctrine of the Trinity. In fact, while I love to lose myself in the details and ponder the complexities of it, I am especially devoted to making sure the main things are the plain things and the plain things remain the main things. I try to teach the old-fashioned, standard, broadly consensual doctrine of the Trinity. Ask me hard questions and I’ll do my best to be thoughtful and responsible, but you can expect me to point to the Bible and to standard Christian confessions. Normie Trinity believer is all I aspire to be. Scratch me and you’ll get the Gospel of John and the theology of Nicaea.

And yet, there are some important elements of the doctrine that seem almost impossible to state in a way that lets the mind come to complete rest. If I were writing in the analytic style, I would try to state these as dilemmas, as problems to be solved, or as research projects. And in scholastic mode, I could lay the material out with a few distinctions that would sort away the paradoxical appearances pretty nicely. But having surveyed such treatments, I continue to catalog these three things as puzzling realities inhering in the primary data of trinitarian faith. Here they are.

- The Father is simultaneously the one God and one of the persons. I know that this same dynamic could be generalized to any person of the Trinity (since the Son, for example, is simultaneously the one God and one of the persons). But there is something special about the Father as the source and anchor of divinity. If you dwell one-sidedly on the Father as the one God, you risk expelling Son and Spirit from divinity; if you dwell one-sidedly on the Father as one of the persons, you collapse the logic of his hypostatic distinctiveness as principle. It’s also worth preserving the logic that confesses the deity of the Son precisely by connecting him to the Father. That is, it would be odd to say “the Son is God, and since the Father is consubstantial with him, the Father is also God.”

- The Son is in some ways like a faculty of the Father (his logos) and in some ways like a counterpart alongside him. If you dwell one-sidedly on the Son as a faculty of the Father, you collapse him into an impersonal power of the Father, or a figure of speech. If you dwell one-sidedly on the Son as a counterpart to the Father, you have a team of apparently self-sufficient entities who are not constituted by internal relation to each other.

- The Holy Spirit is the third person, but a person who is somehow not “out beyond” the Father and Son, but is included in their fellowship. We don’t consider the Father and Son and then say, “but there’s also another one to put into the mix.” The Holy Spirit is somehow a distinct person but not one to whom we turn away from the Father and the Son to attend to.

I state these three issues here as if I were apologizing for them, or admitting to structural weaknesses in my theology, or at least confessing that I’ve failed to see all the way into these matters. But in fact I take them to be built into the basic material of the phenomena that the doctrine accounts for. In another context, I could re-state them as helpful barriers against oversimplifying trinitarianism. In another other context I could brandish a few scholastic distinctions and let the area of illumination spread. But I present them here in a form that risks being intellectually annoying. Perhaps in such a form they invite you to wonder at the things that are beyond us.

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.