A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

Augustine in God’s Word

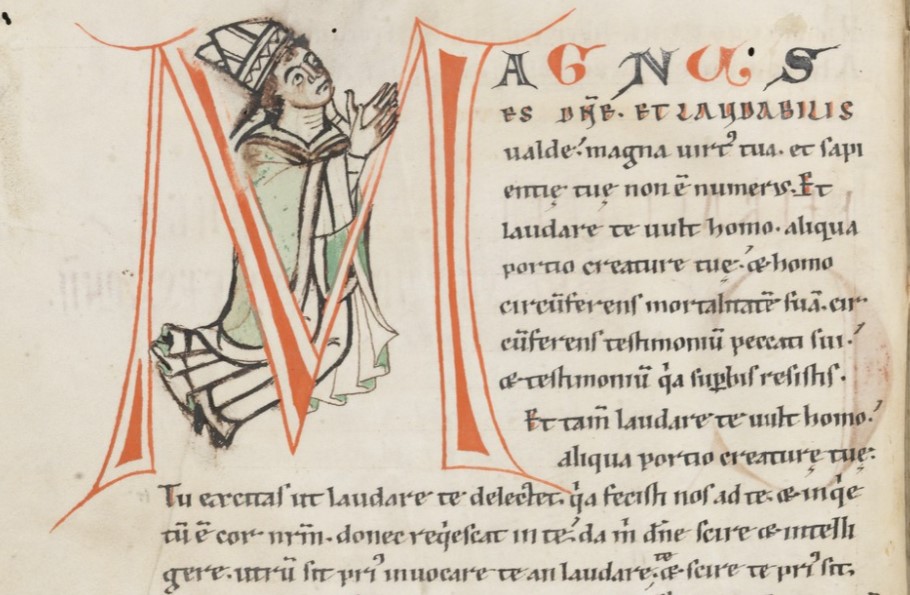

The library of the Dominican monastery in Engelberg, Germany has a twelfth-century copy of Augustine’s Confessions. On the opening page is an illustration (an illumination) of Augustine in prayer. The bishop is tangled up in the first letter of the manuscript, a large letter M. This is mainly just conventional manuscript illumination. Art historians even have a name for a large initial capital letter with a figure painted into it: they call it a historiated capital (or a historiated initial). You see them all the time; they lively up the text.

But there’s something special about this one, because it really does illuminate something about Augustine’s Confessions. If I were to ask what the first line of the Confessions is, most people who know the book would reply, “Our heart is restless until it rests in you,” or the longer version, “You have made us for yourself, and our heart is restless until it rests in you.” And that is certainly a great answer! That is in fact from the opening of Confessions. But it’s not the actual first line.

Since we’ve got the image in front of us, you can look at the very bottom of it. Starting at line 12, halfway through, you get the famous pull quote: “Fecisti nos ad te,” you have made us for yourself.

What happens above that? What are the actual first words of Augustine’s Confessions? Well, that giant M is for Magnus, great. Great are you Lord, and greatly to be praised. It’s the opening of Psalm 48, and Augustine picked it up as the opening of his own book, in which he speaks to God.

You could say Augustine knew that he had to put some of God’s words into his own book if he was going to talk to God properly. That’s practically a thesis statement from Confessions: God’s action precedes ours, and our quest for him is his reclaiming of us. We find our voice by listening to his.

But the illumination shows it even more dramatically: By making the M gigantic, and putting Augustine inside of it, it visualizes not so much God’s words in Augustine’s book, but Augustine in God’s word, from God’s book. He’s dwarfed by it, contained in it, situated interior to it. It goes on and on beyond him. Great is that M, and greatly be be inhabited by the praying bishop.

I do confess, that’s how it is. We find ourselves, come to ourselves, within God’s greater reality. Augustine was a famously good writer (the Confessions really is just astonishingly powerful and well crafted; take up and read!). But another detail the illuminator gets right is that in this iconic opening move, the bishop’s mouth is actually closed for once. He looks up, lifts up his hands, and presents himself to God. All of himself, found in the words of the God who spoke to him. That’s the Confessions.

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.