A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

Voice and Vers: At A Solemn Music

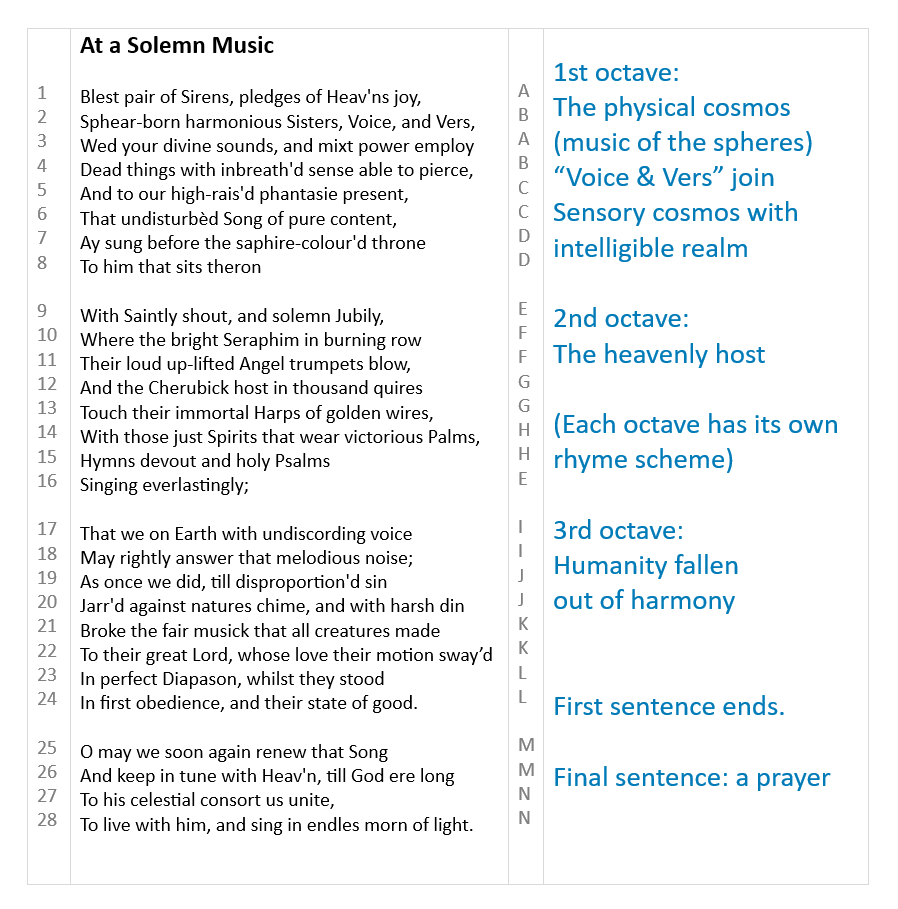

Milton’s early work At a Solemn Music (or Musick) is a remarkable piece of poetry about poetry. Or more precisely, it’s about the joining of voice and verse, or sound and sense, or song and lyric. I recently heard it performed as the closing anthem of an evensong service at Kings College, Cambridge. I knew in advance it would be the anthem for the service, so I read through it a couple of times before going. But I confess I didn’t quite know what I was in for. It’s a masterpiece: the basic idea is immediately evident, and the exalted vocabulary thrills along, giving off glimmers of meaning and sparkles of clarity that all highlight the same basic project of celebrating the power of music itself. But the more you think about it, the more it seems worth thinking about. At 28 lines, it’s a fairly manageable poem, but the first 24 lines are one long sentence. And what a sentence: it’s subdivided into three sets of eight lines each; 8+8+8=24.

Anyway, I’ve been noodling and doodling about it in spare moments since hearing it, and here are some notes. I inserted blank spaces between the octaves. That’s more blatant than Milton’s own presentation of it, but the unit 8 is so important to the structure that I wanted to see it more clearly.

Those sirens in the first line are not the deadly sailor-tempters from Homer’s Odyssey; they are the muse-like creatures stationed on the planetary spheres in the vision at the end of Plato’s Republic. (And okay, Plato was probably riffing on Homer, but with a very creative re-interpretation.) It’s important to identify them that way, because it tips us off that the first octave is all about those cosmic spheres, the physical cosmos. Milton doesn’t want to talk about all eight sirens; only two. These two are Voice and Vers, and when they sing together, they put intelligible meaning into things which are merely material. That’s why the planets sing: they aren’t just grinding gears, but emitters of intelligible sound. And that’s what poetry does: it puts sense into sounds. In a good poem (from the Greek poiema, a thing made or carefully crafted), the same thing is happening as in our sensible-intelligible cosmos.

That’s a lot for the first octave! But it sets you up to see the second octave as going higher, to the angels before the throne of God in a spiritual heaven rather than a physical/cosmic one. The blest pair of sirens are here in the world with us, raising our phantasie to a world above ours. The third octave (“that we on earth with undiscording voice…”) brings in that Miltonic theme of man’s first disobedience and our fall. We have fallen into disharmony; we “broke the fair musick.” And this long first sentence is asking for the personified power of voice and verse to summon us back into undiscording response, to “rightly answer.” The final four lines repeat the petition.

Wow. That’s a poem.

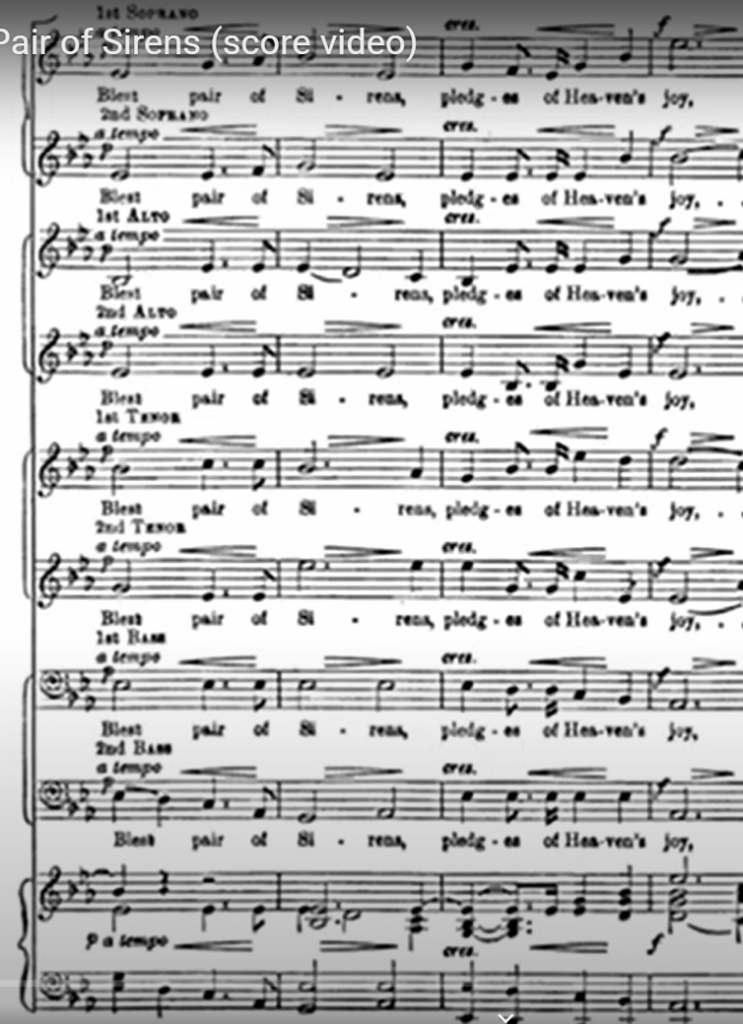

I said that I heard it performed, but more properly I should say I heard Hubert Parry’s 11-minute musical setting of it, which goes by the title Blest Pair of Sirens. (wikipedia entry); here’s one recording of it by the Kings College choir. It’s a gorgeous setting, and the fact that Parry composed it for *eight* vocal parts suggests he was picking up what Milton had put down. If you get to hear it, be ready for the way he plays on the poem’s line 5 (around 2min into the recording), about our ‘high-rais’d phantasie.”

This poem has summoned a lot of good critical writing; for an intro I think it’s hard to beat the 1978 article “At a Solemn Musick: Structure and Meaning,” by Sister Mary Christopher Pecheux, Studies in Philology 75:3 (Summer, 1978), pp. 331-346. Findable on JSTOR.

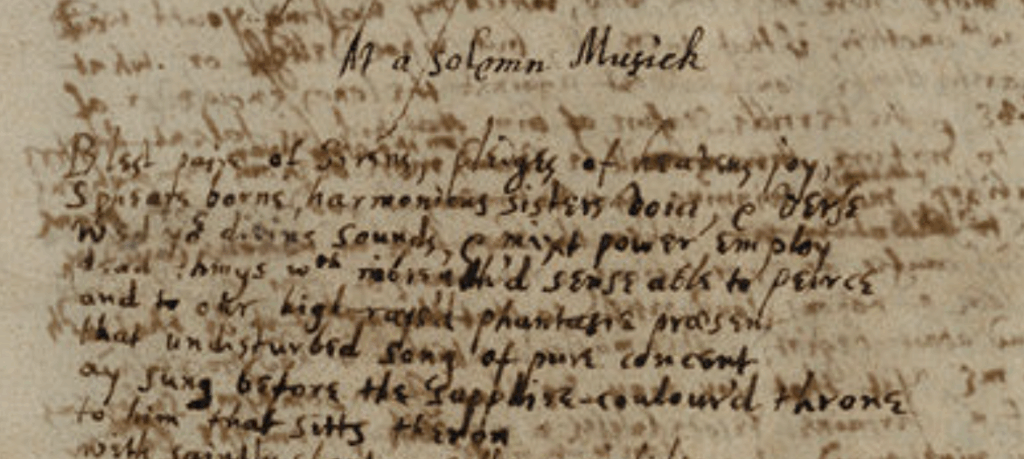

At a Solemn Musick, from ‘The Milton Manuscript’’ in Wren Library, Trinity College Cambridge (shelfmark R.3.4)

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.