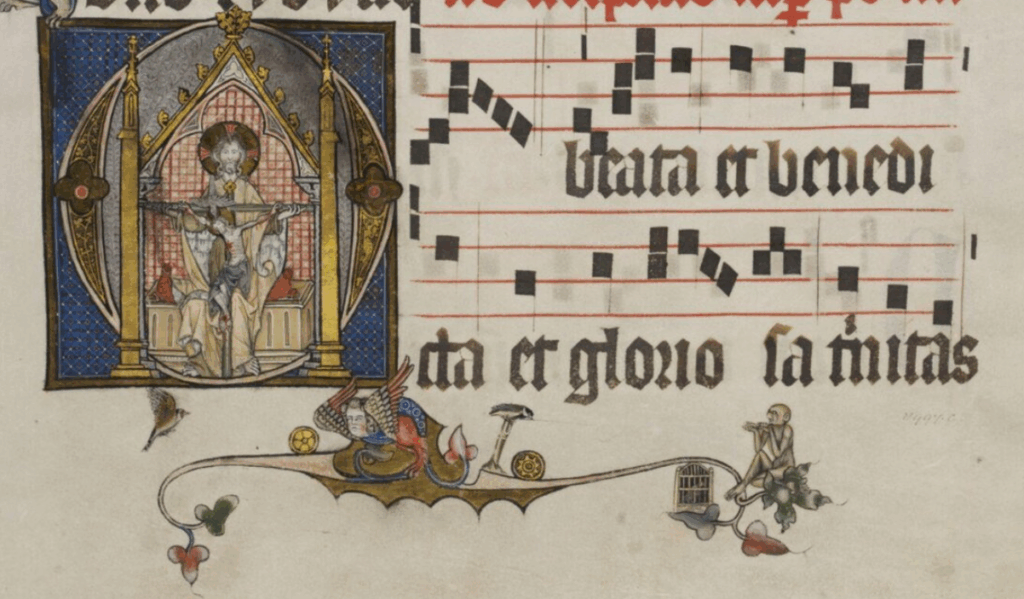

A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

Beata et Benedicta

Pardon the Latin, but I want to make an observation about that particular Latin phrase, and I can’t figure out how to say it briefly in English.

There’s a very old prayer that praises God as beata et benedicta et gloriosa Trinitas. If you’ve heard the prayer anywhere, it’s probably in a musical setting. O Beata et Benedicta has had a thriving career in choral worship. The image on this post is from its appearance in a song book, an antiphonal in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum. See also entries at Choral Wiki, Cantus Database, and Gregobase. Look for choral performances of the versions composed by Palestrina, Mendelssohn, and company. So there’s a bountiful supply of art and music attached to the prayer, but pardon me if I make a beeline for the theology.

God the Trinity is not only beata but also benedicta, though the most obvious way to translate both of these words would be “blessed.” Whoever put the words beata and benedicta side by side in this prayer was forcing a distinction between them.

What’s the difference? Let’s start with benedicta: it means that somebody has spoken well of you, bene dicere, a benediction, a verbal blessing directed at you. If somebody gets verbally blessed by somebody else, we could say they have been blessed, or that they are blessed. If God the Trinity is benedicta, the point is that God has been praised, spoken well of, blessed. The New Testament calls God blessed using a very similar Greek word, eulogētos (Eph 1:3).1

Since it’s always possible that somebody might receive praise who doesn’t deserve praise, this kind of benedicta/eulogētos blessing must carry with it the idea that the person being praised is in fact praiseworthy. After all, if you just say that somebody is popular or highly regarded, you might be making a mental reservation, refusing to say whether they deserve it. That would hardly be a compliment! But to praise somebody as being praised, to bless them by saying they are blessed, entails that they have an inherent goodness that rightly draws forth praise. So benedicta/eulogētos already has a lot going on in it: the Trinity is praised and praiseworthy.

Beata, on the other hand, is something even higher. To be beata is to have beatitude, or the enjoyment of the good itself. If God the Trinity is beata, the point is that God is full, complete, happy, and in that sense blessed. The New Testament calls God blessed in this sense using the very ancient Greek word makarios (1 Tim 6:15).

The key difference is that beata/makarios is more of a direct statement about somebody, in contrast with the way benedicta/eulogētos reflects the way others view, or could view, or should view them. Maybe we could say beata/makarios is primarily about their inward life, while benedicta/eulogētos considers their outward life. Beata/makarios is not yet considering whether anything outside of God answers, or should answer, to the divine standard. It has to do with God’s aseity, independence, perfection in himself. Benedicta/eulogētos considers the same divinity from the outside, so to speak.

O beata et benedicta starts from the inside, or at the top, descending from beata to benedicta to gloriosa. Time would fail us if we tried to include gloriosa, glory, in our considerations: Glory is either the next step out from praiseworthiness to resplendence, or it recapitulates in itself the same two steps just taken in blessedness. If you’ve ever pondered God’s glory, you’ve probably noticed that it includes all these same things: doxa, fama, lux, and so on.

So, a couple of questions: First, how do you say this in English? You can’t say “O blessed and blessed and glorious Trinity,” but maybe “happy and blessed” would work. Unhappily, “happy” sounds lighter than “blessed,” and what we need is for that first word to exert a very great weight. What we need is [something awesome that means classic beata/makarios blessedness but doesn’t use that word] and blessed and glorious.” Selah.

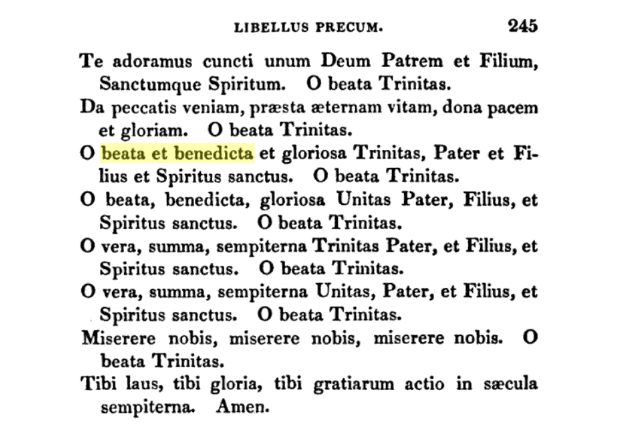

Second, who wrote this? Whose idea was it to put beata and benedicta side by side in a prayer to the Trinity? I strongly suspect, but cannot demonstrate, that Augustine did it somewhere. But until I can document that, let’s settle for that great Augustine fan the Venerable Bede (673-735), who writes it in the beautiful concluding section of his prayer In Laudem Dei Oratio Pura, in his Libellum Precum (PL 94 here; 1843 Works vol 1 here):

It may also have spread via Alcuin (735-804); see three occurrences here.

I’m a little unclear on how it propagated throughout the middle ages, but propagate it did. It was used as an antiphon in all sorts of chant, but especially with Psalm 50 and with the liturgical use of the Athanasian Creed, and especially on Trinity Sunday. Mechthild of Hackeborn (1241-1298) reports that she learned “how to sing the psalm Miserere mei Deus (Have mercy on me, O God, Ps. 50). It has twenty verses, which should be divided into four sections…and sung with the antiphon O beata et benedicta et gloriosa Trinitas, Pater et Filius et Spiritus Sanctus and the verse Miserere, miserere nobis.”

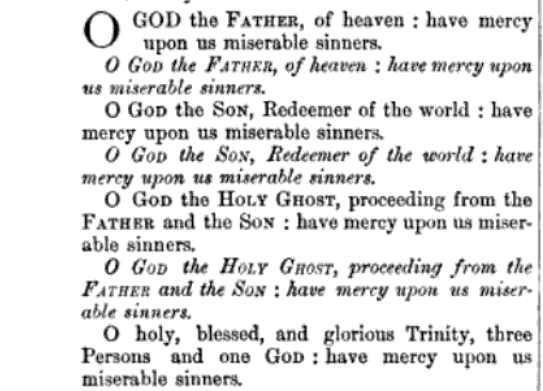

The trail picks up again, sort of, when Cranmer incorporates a version of beata et benedicta into the Great Litany in the Book of Common Prayer. In English, it is: “O holy, blessed, and glorious Trinity, three Persons and one God: have mercy upon us miserable sinners.”

This screencap is from this old annotated BCP; for Sarum Rite see here; for Anglican Service Book commentary see here; for fights about this stuff, consult your local Anglicans.

G.J. Cuming points out that Cranmer has drawn many things together here, from the processional language of the Nicene Creed to the “have mercy” of Psalm 50 to the “three Persons” of the Athanasian Creed. It seems like anywhere beata et benedicta has been hanging around as an antiphon over the centuries, Cranmer wanted to gather it all in for liturgical resonance. Typically Cranmerian craftsmanship.

But notice what Cranmer has done in English with beata et benedicta et gloriosa: “Holy, blessed, and glorious.” Probably with full awareness of how supercharged beata is when you set it alongside benedicta, and having a pretty good ear for What English Can And Cannot Do, Cranmer reaches out for a different word here, and settles on Holy. It’s hard to complain about that word—So biblical! So Trinity-adjacent! So theologically weighty!—but it’s also hard to pretend that it’s doing the actual work of representing the underlying beata. What has become of the blessed Trinity’s highest blessedness? It’s still there in substance, but it has surrendered its etymological equipage and has handed over its job to holiness. But there’s been a compromise, with Cranmer following one specific strategy for how to represent a massive truth with an economy of words.2

So beata et benedicta has a strange afterlife, in disguise as “holy, blessed, and glorious” wherever the Book of Common Prayer is used. Perhaps the mind of the worshiper, cascading down from “holy” to “blessed” and on to “glorious” has the opportunity to mark the movement of the Triune God’s inherent splendor in these three steps.

_________________________________

1I’ve focused on the etymology here for instructive purposes, but bear in mind that no matter how the Latin benedicta or the Greek eulogētos were assembled, their word-origins may be simply a background issue rather than the determiner of their actual meaning. We can call God benedicta/eulogētos without mainly intending to say that somebody is speaking well of God; in fact in Ephesians 1:3 the same word-root eulog- is made to refer to how we bless God and how God blesses us. The operative idea in at least one of these cases isn’t speech, but the actual conferring of some good (a beneficence rather than a benediction).

2With more room to move, more liberty of diction, and no worries about English translation, Dionysius the Carthusian wrote a hymn that solved a similar problem with blessedness differently:

O fons beatitudinis,

Fons omnis pulchritudinis,

Superbeata Trinitas,

Immensa, pura bonitas.

Having called the Trinity the fountain of beatitude (fons beatitudinis), he recognized that it wouldn’t be right to just call the Trinity beata, blessed. So he called God super-blessed, superbeata Trinitas. Putting “super” on the front of something good is a strategy Dionysius the Carthusian (1402–1471) must have picked up from his namesake, Pseudo-Dionysius. But the actual coinage superbeata may be original with the Carthusian.

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.