A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

Not Just Cooperation: The Action of the Three

When three people work together on a project, each of them does their own part of it. As Gregory of Nyssa describes it, “even if several are engaged in the same form of action, [they] work separately each by himself at the task he has undertaken, having no participation in his individual action with others who are engaged in the same occupation.” There are distances and differences between them: they take turns (distance in time), or work on different parts of the project (distance in space), or come to the project from different angles (again, space). “Each of them is separated from the others within his own environment, according to the special character of his operation.”

The reason Nyssa spent time itemizing the nature of cooperation is so he could explain that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit don’t work together in that way:

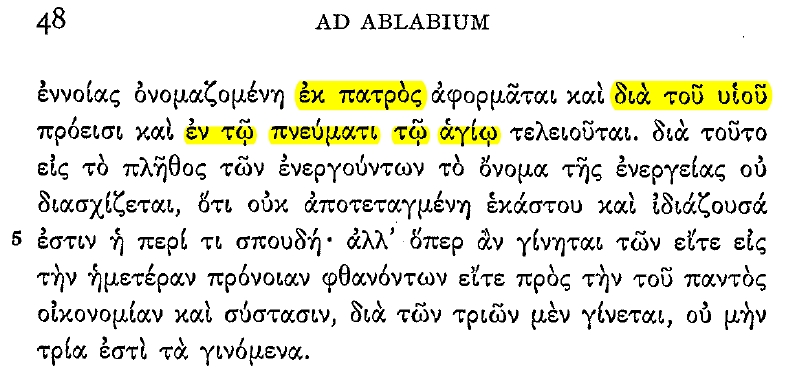

But in the case of the Divine nature we do not similarly learn that the Father does anything by Himself in which the Son does not work conjointly, or again that the Son has any special operation apart from the Holy Spirit; but every operation which extends from God to the Creation, and is named according to our variable conceptions of it, has its origin from the Father, and proceeds through the Son, and is perfected in the Holy Spirit. For this reason the name derived from the operation is not divided with regard to the number of those who fulfil it, because the action of each concerning anything is not separate and peculiar, but whatever comes to pass … comes to pass by the action of the Three, yet what does come to pass is not three things. –Gregory of Nyssa, “Not Three Gods” (NPNF2, 5:334)

This is a classic statement of the inseparable external operations of the Trinity. “Every operation…has its origin from the Father, and proceeds through the Son, and is perfected in the Holy Spirit.” Each of these operations manifests a divine power coming forth from the divine nature. Each of these actions that “extends from God to the Creation” is a work in which the Father, Son, and Spirit work indivisibly, but according to the order “from the Father…through the Son…in the Holy Spirit.” That order is carried over from the internal life of God, so that it is reflected in the external works. So each divine work is inseparably the work of all three persons in unison, though we can recognize each of them in it. We recognize them not by the differences or distances in their ways of working, but by the repetition of their eternal order, which we can indicate prepositionally: from, through, in.

Inserting this “from-through-in” dynamic into each act of God may seem like an unnecessary complication when all you want to say is that God did something, but it’s actually more or less what you might expect, given the oneness of God in Father, Son, and Spirit. According to Nyssa, if you had three different actions and counted backward along that line to three different operations that produced them, you would have no reason to suspect a single divine nature behind it all. If, on the other hand, you knew that the Father begets the Son, and that the Spirit proceeds from the Father of the Son, then it would make sense to say that that eternal order of oneness would also be reflected in their way of working, when they work an external act in which they are inseparable but not indistinguishable.

The Nyssa passage above is taken from “Not Three Gods,” which is most widely available in Schaff and Wace’s Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series 2, volume 5, pages 331-336. Scholars refer to it as “Ad Ablabium, Quod non sint tres dei,” and cite it from Gregory Nyssa Opera (GNO) III/1, 37-57; it can also be found in Migne’s Patrologia Graecae 45, columns 116-136. It’s the very first entry, alphabetically, in The Brill Dictionary of Gregory of Nyssa, ed. Lucas Francisco Mateo-Seco and Giulio Maspero, trans. Seth Cherney (Brill, 2010), where a guide to select secondary literature can be found.

Oddly, in a lot of twentieth-century theology this treatise, or at least some of its language and imagery, was frequently cited in service of a social trinitarian vision in which the three persons of the Trinity were described as straightforwardly doing different things. This vision was labelled “Eastern” and was contrasted with the doctrine of divine simplicity in the Latin West; or as a personalist or hypostasis-centered version of trinitarianism that was contrasted with an essentialist Western trinitarianism. In some cases, the justification for reading the treatise this way seems to have been that the Cappadocian doctrine of the triad was so thickly social that Nyssa had to go out of his way to explain why it didn’t result in three gods. It is an odd interpretation to put on an argument that explicitly depends on the infinite difference between the coordinated work of three creaturely people and undivided work of three divine persons. That error was taken apart ably by Lewis Ayres in “On Not Three People: The Fundamental Themes of Gregory of Nyssa’s Trinitarian Theology As Seen in To Ablabius: On Not Three Gods,” Modern Theology 18:4 (October 2002), 445-474.

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.