A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

“Blessed Art Thou, O LORD” (Manton)

Thomas Manton (1620–1677) had a lot to say about human blessedness. His megamassive three-volume commentary on Psalm 119 takes its keynote from that opening beatitude, “Blessed are the undefiled in the way, who walk in the law of the Lord.” But his doctrine of human blessedness is firmly based on a doctrine of divine blessedness, the blessedness of God, which he makes explicit when he turns his attention to Ps 119:12, “Blessed art Thou, O LORD, teach me thy statues.”

As a preacher, Manton was reliably focused on letting his text pose the key questions. Accordingly, what he is most interested in Ps 119:12 is what the first statement has to do with the second: What is it about God’s blessedness that leads the Psalmist to ask God, “teach me thy statutes?” It’s a good question. And it opens up into a rather finely elaborated theology of human blessedness (the project of the entire Psalm) against the horizon of divine blessedness (the focus of this verse).

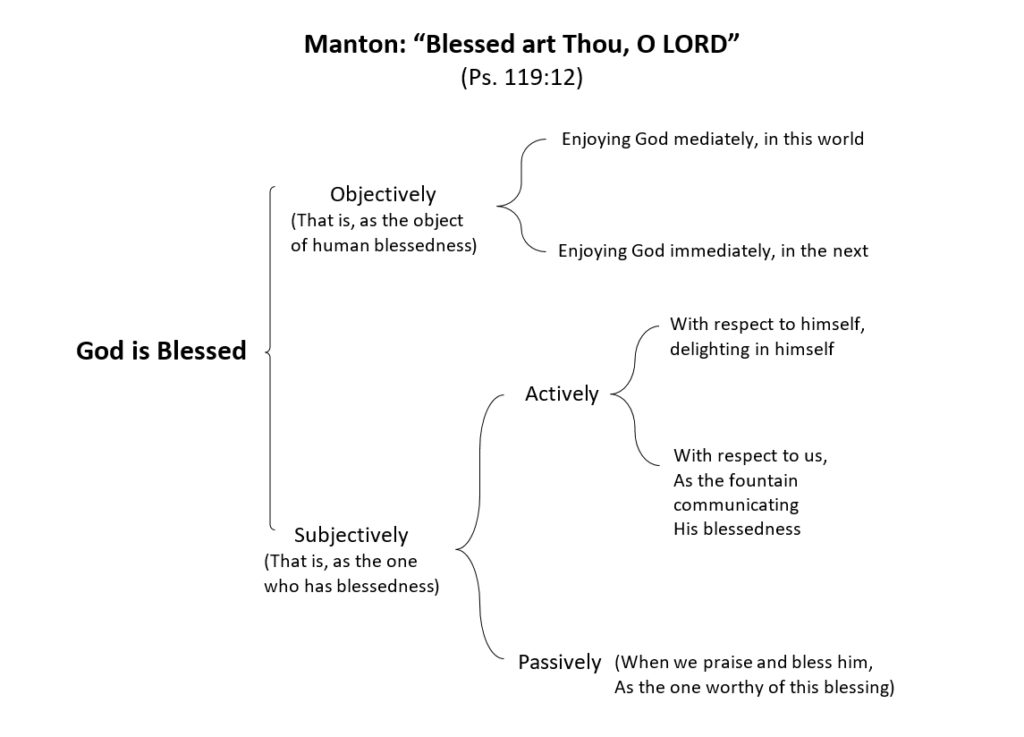

Manton’s first move as a preacher was often to subdivide his text into an easily grasped logical outline. Many of his outlines are simple and sharp, producing instant “aha!” moments. Others are more elaborate. The subdivision of 119:12 is among the more elaborate. Here is a visual diagram of Manton’s analysis:

In calling God “objectively blessed,” Manton means almost the opposite of what most modern readers would take that phrase to mean: he means that God can be said to be blessed because human blessedness (“happy are those who…”) has divine blessedness as its object. God is the object, that is, of our blessedness.

‘Blessed art thou, Lord ;’ that is, Thou art the object of my blessedness ; my blessedness lieth in the enjoyment of thee ; therefore teach me thy statutes. If God be our chiefest good and our utmost end, it concerns us nearly to learn out the way how we may enjoy him. (108)

But there is also a blessedness of which God is the subject, the blessed one. This is divine beatitude itself, though even here Manton distinguishes some senses:

God’s blessedness is that attribute by which the Lord, from himself, and in his own being, is free from all misery and enjoyeth all good, and is sufficient to himself, and contented with himself, and doth neither need nor desire the creature for any good that can accrue to him by us. Or, more shortly, God’s blessedness is the fruition of himself, and his delighting in himself. Mark, it lieth not in the enjoyment of the creature, but in the enjoyment of himself. God useth us, but doth not enjoy us. As we enjoy a thing for itself, but we use it for another ; so uti and frui differ: we use the means, but enjoy the end. God useth the creature in subserviency to his own glory.

The statement that “God useth us” may be jarring to readers who don’t recall Augustine’s distinction between enjoying (loving something for its own sake, absolutely) and using (loving something as a means, relative to something that can be loved absolutely). When Manton adverts to the Latin terms (uti and frui, from which we get English words like utility and fruition), he is invoking the opening lines of Augustine’s De Doctrina Christiana. In fact, those opening lines contain in microcosm the entire structural outline of Augustine’s influential book, and his hermeneutics of Christian teaching. Peter Lombard picks up this same distinction, in turn, in the first two pages of his Sentences, again as both opening gambit and as structuring principle. And since writing a commentary on Lombard’s Sentences was for centuries the medieval way to prove oneself competent to teach doctrine, you may begin to get the impression that we are dealing here with a fundamental category for grasping all things as part of a system of ordered loves.

The reason you might get that impression is simple: we are dealing here with a fundamental category for grasping all things as part of a system of ordered loves. Augustine (and I am tempted to say The Entire Christian Moral and Metaphysical Tradition, but I’ll pretend to be exercising restraint) applied this to our loves. We should love God alone as an end in himself, with the appropriate frui/enjoyment love, and we should love all other things insofar as they lead us to God, with appropriate uti/using love. Augustine did admit that, having mastered this distinction, we could go on to speak lawfully of loving other people with a kind of final-enjoyment-love available to those mutually gathered in the divine neighborhood (frui proximo in Deo).

What Manton does is apply this uti/frui distinction to God’s own love, in order to explain God’s blessedness. God uses the means in subservience to the end, and “His happiness lieth in knowing himself, in loving himself, in delighting in himself.” In a later summary, Manton will emphasize God’s absolute independence by saying “the world is upheld as stones are in an arch, by a mutual dependence, by a combination of interests. We need one another, but God doth not stand in need of us.” (111)

With God’s own blessedness in mind, Manton is able to address his most pressing question, which is why “Blessed art thou, O LORD” gives rise to the prayer, “teach me thy statutes.” The answer is that God knows how to be happy, so we should ask him to instruct us in that way of blessedness that he inhabits:

If God be blessed, we had need to inquire after his statutes, for these teach us the way how we may be blessed in God’s blessedness, how we may be conformed to the nature of God, and live the life of God, and then surely we shall be happy enough.

Well, then, the consideration of this, that God is blessed, will certainly make us prize his statutes, prize his word, for by that we are conformed to the nature of God, and to the life of God ; we are engaged in the same design wherein God himself is engaged : God loves himself, and acts for himself, and pursueth his own glory. Now when the word of God breaks in upon the heart, we pursue the same design with God. (109)

Who should have happiness if God hath not ? Now, when we learn, God’s statutes, we come to be conformed to the nature of God ; we love what he loves, and hate what he hates, and then we begin to live the life of God. The happiness of God lieth in loving himself, enjoying himself, and acting for his own glory ; and this is the fruit of grace, to teach us to live as God lives, to do as God doth, to love him and enjoy him as our chiefest good, and to glorify him as our utmost end. (110)

Manton has been saying all of this under the heading of God being actively blessed, a heading which includes both God’s act of having beatitude (his active blessedness with regard to himself) and his act of being our beatitude (has active blessedness with regard to us): “God is actively blessed with respect to us as he is the fountain of all blessedness. He is not only blessedness itself, but willing to communicate and give it out to the creature, especially his saints. He fills all created things with his blessedness.” (110)

One consideration that Manton sort of sneaks in along the way is how God’s active blessedness necessarily takes the form of giving. The axiom he appeals to is that “it is more blessed to give than to receive,” and the conclusion he draws is that whoever gives the most is the most blessed, and nobody else gives like God. Manton admits that his axiom is not spoken by Christ in any of the Gospels, but is attributed to him in Acts. But he also takes it to be a summary of “the whole drift of Christ’s doctrine” which was “was to press men to give; it is a more blessed thing.” And in the case of God himself, it applies superlatively: “This is the happiness of God, that he gives to all, and receives of none.”

Turning to God’s passive blessedness, or how he receives blessing, Manton says

God is passively blessed as he is blessed by us, or as worthy of all praise from us, for his goodness, righteousness, and mercy, and the communications of his grace. There are two words by which our thanksgiving is expressed, praise and blessing. You have both in Ps. 145:10, ‘ All thy works shall praise thee, Lord ; and thy saints shall bless thee.’ Praise relateth to God’s excellency, and blessing to his benefits. His works declare his excellency : but his saints, which are sensible of his benefits, they bless him (110)

This distinction between praising and blessing (which I think can also be found in Goodwin on Ephesians 1) is far reaching. Manton reads praise as a response to divine excellency, attributing it to all God’s works; he elevates blessing to a response to divine benefits, attributing it to the saints. This might be true. Selah.

Manton’s main task is expounding Psalm 119 in its full scope. That Psalm’s “exaltation of the Torah” (the title of David Noel Freedman’s treatment) emphasizes the human spirituality that arises from proper recognition of God’s word as what it is. In his dozens and dozens of sermons on the Psalm, he faithfully follows that emphasis. But in Manton as in the Psalm, the human response depends on the prevenient reality of God’s initiative, and behind that, the reality of God’s identity. Human blessedness, in other words, depends on divine blessedness.

____________________________

These notes are based on the sermon on Psalm 119:12 in The Complete Works of Thomas Manton Vol 6, Containing Several Sermons Upon the CXIX Psalm (London: James Nisbet & Co, 1872), 108-118.

I also recommend J. Stephen Yuille’s book Great Spoil: Thomas Manton’s Spirituality of the Word (RHB, 2019), which shrewdly begins with the same move, of highlighting God’s blessedness before turning to human blessedness. The book is a great introduction to Manton by somebody who has read widely in a set of books I’ve only dipped into. Yuille includes lots of topics in spirituality, and provides appendices on meditation and contemplation drawn from Manton sermons on Genesis.

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.