A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

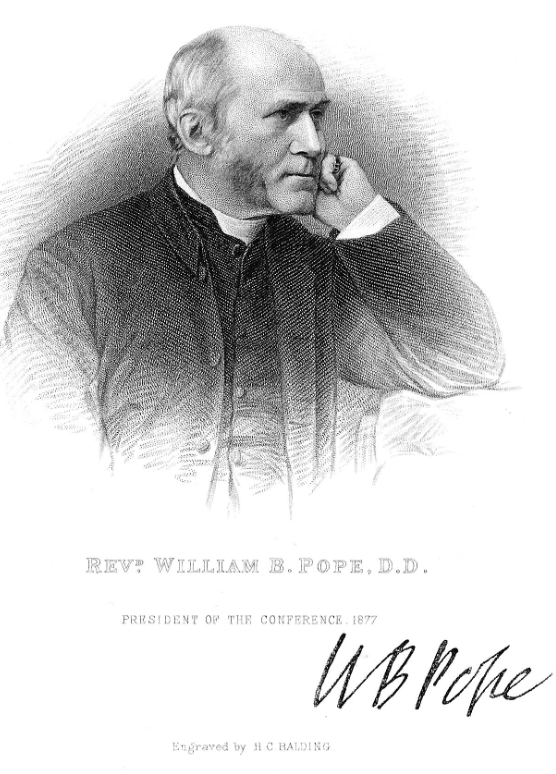

W.B. Pope on “Theological Coinage”

William Burt Pope starts his book on The Person of Christ (2nd ed., 1875) with a few observations about terminology. Specifically, he notes a certain “adjustment of our phraseology” which takes place in Christology, but also more broadly in theology.

Pope considers the task of formulating doctrines to be strictly subordinate to the task of understanding Scripture’s own formulations. He rather laments our need to come up with new language to speak theologically, and wishes it were possible to simply say exactly what Scripture says. But then again, as long as we are coining theological language, we should make sure it’s well-coined. And when it is, Pope is willing to make startlingly high claims for the power of theology. So it’s hard to say if Pope has a low view or a high view of theological terminology.

Here’s how he sets up the discussion: “Generally speaking, the vocabulary of Divine mysteries, whether as to the internal relations or the external manifestation of the Godhead, is governed by laws of its own.” (3) The theologian’s task is to discern those laws, and then explicate them.

The language of the Holy Ghost, who alone searcheth the deep things of God and His Christ, is perfectly simple and unambiguous; and, if we adhered solely to His words, our task would be relieved of much difficulty. But however diligently we attempt this, however fervently we may desire a return in the future to the simplicity of Scripture, it is at present a thing impossible. Theology, as including Christology, is a science humanly constructed out of Divine elements. (4)

Here is the first note of paradox: “a science humanly constructed out of Divine elements.” The human side means the formulations remain fallible. We could be wrong. But the divine side means that when we put together doctrines, we are doing so by handling holy things. Pope characteristically summons his readers to behave reverently toward the words of Scripture, no matter the audience: Theology “must speak to the men of this world in their own language. But, while bound by this necessity, it stipulates for a reverent construction of its terms, and for a certain tolerance which its high subject matter demands.” (4) Theology’s analogies and symbols will never be as clear and distinct as the natural mind demands; the natural mind simply isn’t inclined to reckon with the depth and holiness of the subject matter being discussed. But we do speak a kind of wisdom, after all, or we should strive to.

To those who receive the Bible as God’s oracle among men, theological science vindicates its terminology by showing that it is as close a reproduction of inspired thought as can be made in uninspired language. Our boldness could indeed scarcely be charged with irreverence were we to say, remembering the Lord’s promise, that much of the established and sanctified phraseology of our science is only the reflection of Holy Writ, and little less than the words of a secondary inspiration.

Another strong claim: Properly done, theology’s “sanctified phraseology” can be “the reflection of Holy Writ,” flowing from “a secondary inspiration.”

It’s worth noting that this way of talking is aspirational, but it also presupposes a certain manner of doing theology, a manner well modelled by Pope. What is most fundamental in his own work is the careful interpretive investigation of discerning how Scripture speaks, and then generating theories about why it speaks that way. To take an example from Christology, Pope begins this book by canvassing Scripture for its statements about Christ, and arguing vigorously for “Son” as the central category, to which images like “Word” and “image” bear witness. In arguing for the centrality of Sonship, Pope is attempting to make his “sanctified phraseology” a “reflection of Holy Writ;” if he succeeds, he can claim to be instructing his readers in a way that operates by inspiration –derivative, secondary, subordinate, but still some sort of inspiration.

Pope has in mind here not just the phrases he will have to generate and define in writing his own confessional theology, but also the extra-biblical terms we receive from the ancient creedal and doctrinal forms.

From the word Trinity, the most august creation of human speech, with its assemblage of terms defining the hypostatical relations of the Persons of the Triune nature, down through the whole compass of mediatorial theology to the ordinary phrases of Christian intercourse, there is an abundant vocabulary which finds no precise representatives in the language of Scripture, although it is perfectly faithful to that language as its developed synonymous expression. (4)

Again, Pope is well aware of the gap between the Bible’s speech and our theological response. But even at that, when Tertullian coined the word Trinity to say what Scripture says in other terms, he was responsible for “the most august creation of human speech.” Good theology, including the nontechnical theology of ordinary Christian speech, can be the “developed synonymous expression” of Scripture.

And finally, drawing near to his main subject (the person of Christ), Pope says “Christology has its own

distinct range of theological coinage. Its highest achievement here is the term theanthropos, Deus-homo, God-man ; and with this it boldly utters the secret of the whole Bible.” (4-5)

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.