A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

Journey of the Word (Lessons between Carols)

1. Genesis 3: God Promises a Redeemer

In the beginning, two trees stood in the midst of the garden. There was the tree of life, and there was the tree of knowledge, and they just made sense. They grew side by side, and self-evidently belonged together. The LORD God planted them there as a dual blessing in a world of blessedness, a match made in paradise. But now nobody remembers how they were ever supposed to go together, because Adam and Eve took them apart… and lost the instructions.

Whatever else the LORD God had said about the two trees, he had definitely commanded Adam not to eat from the tree of knowledge of good and evil. That prohibition was holy and righteous, but our first parents called it into question. Their ears had heard the holy word that walked among the ancient trees, but they rejected it; they contradicted it. They stuck their fingers in their ears, stuffed the fruit into their mouths, puffed out their cheeks and said ptttlllbbb.

hat’s when everything fell apart; literally everything fractured into fragments and all stopped making sense. The tree of knowledge had belonged together with the tree of life, but now it was one against the other, knowledge versus life. With the unity shattered and the internal bonds all repolarized and opposed, every “with” became a “versus:” parents versus sons and daughters versus brothers versus sisters versus city versus country versus black versus white versus rich versus poor versus old versus young. A most unfortunate fall into fragmentation.

In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth, but after the great devastation of the primal breakup, it become the heavens versus the earth, because the word of God made its way to man, and man told it to go home. Their only comfort in life and in death was that even after they rejected God’s word, God hadn’t stopped talking.

Looking back on it, Adam and Eve never could agree about exactly what God had said to them on that terrible day in the garden. Adam remembered a lot of shouting and lightning and thunder and some cursing –or at least one tremendous curse, the kind of curse that still hangs in the air and discolors the sky, so that you can’t imagine how you could ever crawl out from under it.

Eve remembered that too, but also a promise: Something about her son –no, her seed– fighting the seed of the serpent somewhere, somehow. This first family may have fractured fatherhood, made a monster of man and a mockery of all mothers, but right here at the vandalized font of our shattered history, God had spoken anew. And what he had spoken was a promise, the first gospel announcement: that his word would not always go unheard and unheeded by the sons and daughters of Adam and Eve, but would surely make its way to them, to be at home among them again, no matter what it cost him.

2. Genesis 12: Abraham Believes God

Father Abraham had many sons, eventually. But for most of his life all he had was his wife Sarah, some servants, and a word-of-mouth promise from the voice of God. For the LORD said to Abram, “Go out, away from the familiarity of your country, and far away from the network of your kindred, and out of the protection and security of your father’s house, to the land that I have not even shown you yet, but will show you later. And I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing.”

So by faith Abraham obeyed, and he went out without even knowing where he was going. God said “go somewhere,” and Abraham said “OK” and headed somewhere. He lived in a tent but looked forward to a city. He waited for a baby, the down-payment on a great nation. He waited– until he and Sarah were past the age of childbearing, and then he waited some more. Now there’s a pregnant pause. He waited until he was as good as dead, all those years remembering the promise and repeating under his breath, “Abba, Father, you can do anything.”

Once Abraham got going, God filled in some of the details along the way. Step by step this pilgrim made progress, and things got clearer, eventually. If you’ve read the Bible, there’s no keeping you in suspense: for Abraham there was a happy ending, eventually. God gave his word and kept it. Finding nothing greater to swear by, God swore by himself. Scripture preached the gospel beforehand to Abraham, and Abraham rejoiced to see the day of Christ. God called Abraham to Canaan. God called Abraham his friend, called him the one who believed, called him a rock that he hewed his chosen people out of. God called himself by the name, “the God of Abraham.” Many will come from the east and the west to recline at table with Abraham; and Father Abraham was a blessing to all the nations of the earth, eventually.

But in the meantime, the times were mean. When Abraham died, the only real estate he owned in the promised land was a gravesite. He lived by faith and died still seeking. But the vindication of Abraham was inevitable, because God had picked his man, put the plan into motion, and given his word. And in the heart of Father Abraham, that word found a home.

3. Micah 5: Bethlehem

The book of Micah is a very small book, somewhere just past the middle of the Bible. It’s somewhere between Amos and Zephaniah, between Obadiah and Habakkuk, between Jonah and Nahum. It’s down where the mighty stream of Old Testament salvation history starts narrowing to a trickle. It’s in a cavern, in a canyon, excavating for a minor prophet. Micah’s in a narrow place, a tight spot for a lot of people who think they can recite the 39 books of the Old Testament, but come to grief in here, where the Hebrew names get thick: Moresheth-gath, Beth-le-aphrah, Zaanan, Beth-Ezel, Achzib. Most of them are 3 or 4 syllables long. They’ve usually got a couple of Zs in them. And around any corner might be lurking a Mephibosheth or a Maher-Shalal-Hashbaz. Nobody accidentally ends up in Micah; it’s so small that you have to go there on purpose if you’re going to go there at all. Micah seems too little to carry much weight in a book like the Bible, with its jumbo sections like the Deuteronomies and Isaiahs and Chronicles.

But here’s little Micah in the middle of our Christmas readings every year. And why? Because of chapter 5, verse 2 and following:

2 But you, O Bethlehem Ephrathah,

who are too little to be among the clans of Judah,

from you shall come forth for me one who is to be ruler in Israel,

whose coming forth is from of old, from ancient days.

3 Therefore he shall give them up until the time when she who is in labor has given birth;

then the rest of his brothers shall return to the people of Israel.

4 And he shall stand and shepherd his flock in the strength of the Lord,

in the majesty of the name of the Lord his God. And they shall dwell secure, for now he shall be great to the ends of the earth. 5 And he shall be their peace.

Micah’s a pretty small book, and Bethlehem is a pretty small place. Not big, not important, “too little to be among the clans of Judah.” But the prophesy says the ruler will come from there, “when she who is in labor has given birth,” and that “he shall be great.” This was a clear prophecy. When the wise men followed the star as far as they could, they had to stop and ask the locals for directions. Herod gathered the chief priests and scribes and asked where the Christ was to be born. That was an easy question for them. They pointed directly to little Micah and said, “In Bethlehem of Judea, for so it is written.”

But why little Bethlehem? Because even if it’s not somewhere big, at least it’s somewhere, and the rule is: Everybody’s Got To Be From Somewhere. None of us start out from nowhere, and none of us start out from everywhere, and Christ came to be one of us, so he started somewhere. Somewhere in particular, at a particular time in a particular nation’s history, in a particular family.

So God the Son, coeternal, coequal, and coessential with the Father, omnipotent and omnipresent like the Holy Spirit, condescended to take up a local habitation and a name, and rolled from heaven to earth in order to body himself forth right there in Bethlehem –of all places.

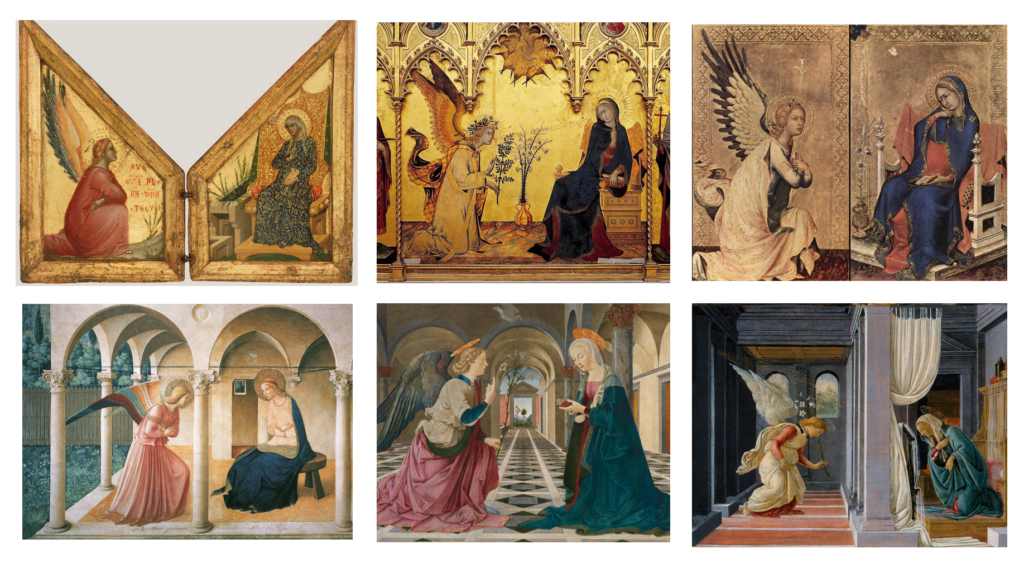

4. Luke 1: The Annunciation

Nobody knows what Mary was doing in her home in Nazareth when the angel Gabriel arrived there from God. Praying? Sewing? Cleaning? It doesn’t matter when you’re telling the story, but if you’re painting it, you have to decide. But one thing almost all the painters agree about: in this scene, the Annunciation, they put Mary on one side of the painting and the angel Gabriel on the other, with a gap between them. Sometimes it’s a large gap, as if Gabriel is shouting from across the room. Sometimes there is architecture between them, like posts or columns or half-walls.

Gabriel is bringing a message from God, and the message that he brings has to come from far away and leap across a great distance to reach its human hearer. The distance his voice is traveling is the distance between two worlds. A herald from the kingdom of heaven speaks the word of God to a daughter of Eve on earth. After all these years, what God the Father has to say is something about his own Son.

So when that almighty word comes from heaven to earth, it finds a home. “Mary,” says the angel, “you will conceive in your womb and bear a son, and you shall call his name Jesus. He will be great, and will be called the Son of the Most High. And the Lord will give to him the throne of his father David, and he will reign over the house of Jacob forever, and of his kingdom there will be no end.”

The word came across an unimaginable distance, and spoke an unbelievable promise, but the unbelievable promise is believed. Mary does have a question: “how shall this be?” And the angel answers, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you, and the child to be born will be called holy, the Son of God… not a single word of what God says shall be impossible.”

“I am the servant of the Lord,” says Mary, “Let it be to me according to your word.” Mother Mary echoes Father Abraham, and both of them sound like the seed who was promised so long ago; like the Son who will say “Abba, Father, all things are possible for you.”

5. Matthew 1:18-25: Jesus Immanuel

This baby shows up loaded with a lot of names: Wonderful counsellor, mighty God, prince of peace, Messiah, Son of the Most High. But when the time draws near to fill out the birth certificate, it will be Joseph who steps in as the step father, to do the duty of a dad and put a name on the boy. And that name is not browsed from a baby book or shaken down from any family tree, but comes directly from God the Father through an angel, who tells Joseph, “you shall call his name Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins.” The name Jesus means “the LORD saves.”

And not only that, but he also comes with yet another name, which is neither a nickname nor what’s on his driver’s license, but a prophetic identity marker that Matthew plucks out of Isaiah and reminds us about. It puts into one mighty word the significance of who he is: Immanuel, which means, God with us. Taken together, Jesus plus Immanuel is a mouthful: The LORD saves because God is with us. Now that is a well-named baby.

Speaking of a lot of names, Matthew begins with a genealogy of dozens of ancestors of Christ. The first bracket runs from Abraham to David, and we know those names from the early part of the Bible; these are all characters we recognize. The second bracket runs from David down to the Babylonian captivity, and we at least know those names from the books of Kings and Chronicles. This is a royal line, even if some of the kings were stinkers.

But the third bracket runs from Babylon to the time of Jesus, straight across that 400 year gap between the Old Testament and the New. We don’t have any record of those names anymore except what’s here in Matthew. They were not kings. By Joseph’s time they’ve got pretty humble craftsman jobs like builders. They’re not exactly losers, but they’re mostly lost to history. But although history dropped out their names, God did not. None of them were lost or forgotten. He knew them, and the lineage they traced was in fact the one line God had his eye on the whole time, a straight line from Father Abraham down to the Son of God, Immanuel, Jesus. Remember: God knows our names, and gives us his.

6. Luke 2:1-7: The Birth of Jesus

Caesar Augustus was ruler of Rome. He called himself Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Divi Filius Imperator, and throughout the Roman Empire his subjects called him son of God and lord of all. When he spoke, people moved. Now it came to be that in those days Caesar Augustus wanted to count his subjects, so he decreed that everybody in the known world had to go back where they were from and hold still in their proper cities long enough to be written down.

That’s why a man named Joseph went from way up in Galilee in northern Israel, all the way down south into Judea, to David’s city, Bethlehem, with Mary, his pregnant wife. And it came to pass that she bore a son. But there was no room for them in the inn, so she wrapped him up and laid him down in the manger, the animals’ food-box, where animals mange or munch on hay.

t’s an odd place to put a baby. You probably don’t have a manger in your house unless you put one there for Christmas. The functional equivalent of a livestock food-trough in suburban life would be something like a dog dish (though that’s not the right size. Or maybe the kitchen sink. Or a big tool box in the garage. Or a filing cabinet. If there’s no room to put a baby, and you start looking around to improvise, you might come up with the sock drawer in your dresser, or a reclining chair with some extra couch pillows. Ba-rum-pa-pum-pum, just get it done!

No doubt Mary and Joseph did the best they could with a hard situation in an inhospitable world. And I’m sure the baby didn’t mind. He probably didn’t say a mumblin’ word. But in a world where Caesar Augustus is the one called son of God and lord of all, and everybody has to go where he tells them to, the long-promised seed of the woman, the actual son of God, the real Lord of all, was tucked away pretty much anywhere he would fit.

7. Luke 2:8-21: The Shepherds

I have so many questions about angels. Do they fly by flapping their wings, or more like Superman? Do they sing? What do you call a group of angels? A herd of cows, a flock of sheep, a what of angels? A choir? A host? An alleluiah of angels? A pyro of angels? There’s so much we don’t know about angels.

When the angel appeared to the shepherds to tell them the good news of the birth of Jesus, he made his announcement, told the shepherds how to recognize baby Jesus, and then: “Suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host praising God and saying, “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth, peace among those with whom he is pleased.”

One angel is really something. But how do you respond when the whole sky is festooned with a whole, festoon of them? (A flap of angels? A fluttering of angels? A chandelier of angels?) In the Old Testament there’s a story about Elisha’s house being surrounded by an angry army and his servant being scared. Elisha says “Fear not. There are more on our side than on theirs,” and when the servant looked again God had opened his eyes to see the hillsides covered with angels. The whole valley around the house of the prophet is one big bowl full of angels. (A bowl of angels? A jazzhand of angels?)

That must have been what it was like for the shepherds to see the one spokes-angel all at once surrounded by an upside-down colander of angels, the whole curvature of the sky populated by these mysterious messenger-beings. It’s as if the descent of the Son of God had poked a hole in the canopy of heaven and all the angels leaked out at once. Hark, how all the heavens did ring with their words!

They spoke the message from heaven above, and it bounced off of the hills below, opening an antiphonal echo chamber between earth and sky. It took a host of angels –a sparkle of angels? A pompom of angels? An awning of angels? –to get it done, but listen: Do you hear what I hear? The word of God was coming down from above and instantly being answered from below, as the earth gave back the song that now the angels sang, and repeated the sounding joy: Glory to God up there in the highest, and peace to men down here on earth. He shall be our God, and we in reply shall be his people. The name of God will be hallowed on earth as an echo of how it is hallowed in heaven.

8. John 1: The Incarnation

We’ve said a lot of things tonight. We’ve used so very many clumsy words, and we’ve sung so many beautiful ones –but now they’re all gone. They came out of our mouths and echoed around us for a while but then they faded out. Everything we’ve said and everything we’ve sung, all the lessons and all the carols, bounced around inside these walls and then vanished.

When God speaks a word, it’s not like that. The psalm says, “Once God has spoken, twice have I heard this: that power belongs to the Lord.” When God says something, it stays said. Our words are insubstantial, but God’s word is substantial, even consubstantial. You and I can send a word out without meaning much by it, or without being really committed to it. But when God speaks, he puts himself into it. When the Father spoke the biggest thing he ever said, what he said was “this is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased. Listen to him.” And what the Son said back was “Abba, Father, you can do anything.”

And when the Father and the Son talked to each other about us in the Spirit, what they said arranged for our salvation. They said God with us, to save his people from their sins, peace on earth, here in our own place and in the fullness of God’s good time. In the fullness of time, God sent forth his Son, born of a woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the curse of the law. And he sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying “abba, Father.”

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made. In him was life, and the life was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it. … He came to his own, and his own did not receive him. But to all who did receive him, who believed in his name, he gave the right to become children of God, who were born, not of blood nor of the will of the flesh nor of the will of man, but of God.

And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth. For from his fullness we have all received, grace upon grace. For the law was given through Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ.

The journey of the word of God to live among us was not an easy trip. It was the Son of God making his way into the far country, bringing the life of God down here among us: within earshot, within range, within the manger at Bethlehem and within this room where God’s own word is spoken and sung. The word of God is very near you. Once God has spoken: And what he has said, and what he says now, is Jesus Christ. Today if you hear his voice, don’t harden your heart. Tonight listen to the Father say “this is my beloved Son; hear him.” This season, open your ears, open your hearts, open your lives to receive what God says in Christ.

The journey of the word of God to live among us was not a cheap excursion. It was an all-involving journey, requiring the full commitment and total consecration of the savior to his mission. The salvation that Christ brought to us cost him dearly, just as it cost his Father in heaven a price nobody else, not one of us, not all of us together, could afford. But on Christmas, it’s a little rude to dwell too much on what the present cost. It’s the time to take and say thank you, to rejoice in the gift: God the Father so loved the world that he gave us the presence of his only begotten son, that whoever believes in him might not perish, but have everlasting life.

_____________________________________________________________

This is a set of lessons we used at my church for our annual Christmas concert. I wrote a version of it in 2014, but cleaned it up and shortened it a bit for this year’s reading. The lessons work best when they come between songs, and are even designed in part to pick up on some of the lyrics in Christmas songs. And of course if the songs are well chosen and wonderfully performed, the little prose lessons have the easy job of coming in and doing some explaining. It also works well to have two narrators trade off paragraphs (my wife Susan performed this reading with me; it was great to get the band back together on tour).

With the incarnation of the Word in mind, the central thread of these lessons is the notion of God’s word addressing humanity. The running narrative is about humans rejecting that word, sending it away until it makes its triumphant return. Someday I’d like to annotate the script a little bit: there’s Blake and Shakespeare and Eliot and Barth and Michael Card running around in here somewhere. But that stuff is supposed to be allusively backgrounded as you read or hear the piece.

A few friends have used this script, or parts of it, at their own churches. If you like it, feel free to do likewise. I’d love to get due credit, and to hear about it if you do that. You can use the contact page here at fredfredfred to do that.

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.