A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

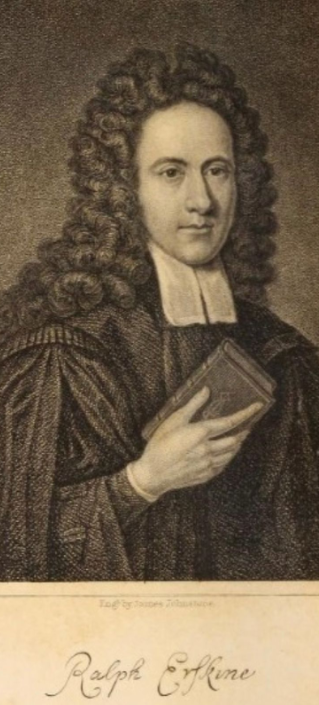

Erskine on the Son’s Presence

Ralph Erskine (1685-1752) wrote voluminously but not systematically, so tracing out a line of thought in his work can be a challenge. I’m jotting down some notes here on a line of thought I’d like to pursue sometime.

Erskine’s got a theology of the presence of the Son which I think presupposes a notion of trinitarian mission; it presupposes it but doesn’t quite make it explicit. In the places where I expect him to say “the Son from the Father,” he tends to say “God in Christ.” He does have a high, traditional trinitarian theology, but when he speaks (as he often does, quite resourcefully and deliberately) of direct, experiential contact with God in Christ, he tends not to connect the trinitarian dots. Of course “God in Christ” means the Father sent the Son, and Erskine knows that. But his theology offers a chance to develop an experiential, Protestant theology of trinitarian mission more explicitly than he himself did.

Probably the best starting point is Sermon 89, “The Combination and Conjunction of Joys, or, the Joyful Approach of the Saviour, chearfully Welcomed by the Church’s Echo of Faith.” in Sermons and Other Practical Works, volume 6, 61-89. There he describes how Christ comes to us in the flesh (incarnation), on the clouds (second advent), in the word, and by the Spirit.

In the same volume, you can trace some of the experiential vicissitudes of receiving Christ’s presence: Sermon 95, “Sensible Presence, Sudden Absence: or, the Believer’s most comfortable Interviews but of short Duration,” 175ff.

And the trinitarian background: the Holy Spirit’s origin from the Father and Son in Sermon 97, “The River of Life, Proceeding out of the Throne of God and of the Lamb,” 232ff. The Father’s presence in the incarnate Son, Sermon 102, p. 359ff, “The Sum of the Gospel; or , God in Christ.” The way eternal generation stands behind the incarnation, Sermon 140, “Heaven’s Grand Repository, or the Father’s Love to the Son, and Depositing All Things into his Hand,” etc. vol 6, 111ff.

And finally, because of Erskine’s realism in describing the way Christ is present to us in this sending, he became embroiled in some conflict about whether he meant that believers ought to be having sensible experiences of visible phantasms of Jesus Christ in person. His answer is Faith no Fancy, explaining that he’s not talking about that sort of stuff at all. The tract is harder to read than his sermons, because Erskine had no skill for controversy but he thought he did, and when he fights he does so defensively and tiresomely. (Note to self: compare Erskine to Fletcher on the spiritual manifestation of the Son of God to believers.)

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.