A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

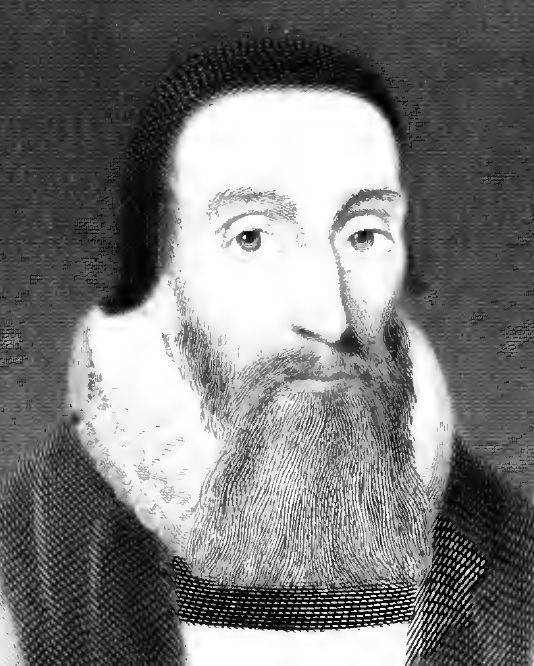

Grace Times Three (Davenant on Colossians)

When John Davenant (1572-1641) hits the word “grace” in the opening of Colossians, he has much to say. His Colossians commentary is admirably copious (about 900 pages). But he’s never just filling up pages or chasing word count. Davenant on Colossians has a constant eye for theological interpretation.

By way of greeting, Paul says “grace to you.” Earlier Davenant had acknowledged the word’s use (alongside “truth”) as a salutation, Here he digs in and informs us that the term grace denotes three things :

First, the gratuitous act of the Divine will accepting man in Christ, and mercifully pardoning his sins. This is the primary meaning of this word, which the Apostle every where enforces. By grace are ye saved (Eph 2:5); Being justified freely by his grace (Rom 3:24). This gratuitous love of God is the first gift, says Altissiodorensis [William of Auxerre], in which all other gifts are bestowed. Aquinas acknowledges this grace of acceptation (Quaest. Disp. de grat. Art. 1).1

First things first: Davenant waves his hand broadly at “the primary meaning” of grace as the basis of salvation and justification. It’s the Perfectly Predictably Protestant emphasis on God accepting sinners out of free love, forgiving them. With that established, Davenant goes on to canvass other meanings:

Secondly, under this term grace the Apostle comprises all those habitual gifts which God infuses for the sanctification of the soul. So faith, love, and all virtues and salutary endowments are called graces. The words of the Apostle in Eph 4:7 have this sense: To every one of us is given grace according to the measure of the gift of Christ. The Papists acknowledge this inherent grace almost exclusively; and in the mean time think too lightly of that accepting grace which is the fountain and well-spring of it.

“Grace” also points to a change brought about within the saved. It’s a general term comprehending “all those habitual gifts,” the “virtues and salutary endowments” that God gives us. He gives them by infusion, and they work their way out in the experience of sanctification, renovating our souls and becoming inherent, built-in, to who we are. So this is infused grace. A Protestant like Davenant gladly teaches infused grace, but warns that Roman Catholic theology tends to think of this kind of grace as the main thing or even the only thing. From Davenant’s point of view, to play up infused/inherent grace at the expense of imputed/accepting grace would be to cut off the river from its source. Davenant is the kind of Protestant whose mind is catholic or comprehensive enough to want everything. And the way to have everything is to think bigger than Roman Catholicism’s narrowing of grace: lift up your eyes to the fountain of free grace from which the transforming power of infused grace flows.

Lastly [third], grace denotes the actual assistance of God, whereby the regenerate, after having received habitual grace, are strengthened to perform good works, and to persevere in faith and godliness. For to man renewed and sanctified by grace, the daily aid of God is still necessary for every single act.

“Give me grace!” we might cry out in a hard situation, and when we do so we don’t mean either of the first two. We use “grace” to mean divine help and an endowment of strength here and now for the present challenge.

Davenant distinguishes three meanings of grace not to isolate them from each other, but to articulate how we need them all and have them all. “Grace” means God’s free favor, personal transformation, and daily help.

When therefore the Apostle wishes grace to the Colossians, he desires for them the gratuitous favour of God, the habitual gifts of sanctification, and the unceasing actual assistance of God. The union of all these is necessary : inherent grace is not given unless the grace of acceptance has preceded it ; neither being given is it available to the production of fruits, unless also the efficacious help of God follow and accompany it through every individual action.

When he eventually gets to the part of the verse that says “grace and peace” come from God the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ, he will run back through all three meanings again, now attributing them to the Father as the fountain and the Son as the reservoir; the communication depends finally on the Holy Spirit (not mentioned here by Paul), so that trinitarian grace is the blessing Paul prays for the Colossians.

_______________________

1The Latin editions of Davenant on Colossians that I checked don’t have this line, “This gratuitous love of God is the first gift in which all other gifts are bestowed.” And they don’t name-check Altissiodorensis as its source. I conjecture that the English translation must be from a later edition that has some expansions–maybe? I would like to know more about Davenant’s use of William of Auxerre; he cites him here right alongside Aquinas, though Aquinas is in our day quite famous, while Altissiodorensis is so obscure it’s funny.

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.