A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

How to Read a Charles Simeon Sermon

Charles Simeon (1759-1836) published sermons on the whole Bible. Or rather, he produced a kind of commentary on the whole Bible in the form of sermons. Or rather, he worked through the whole Bible showing how each passage could be preached effectively, with a constant eye on the gospel.

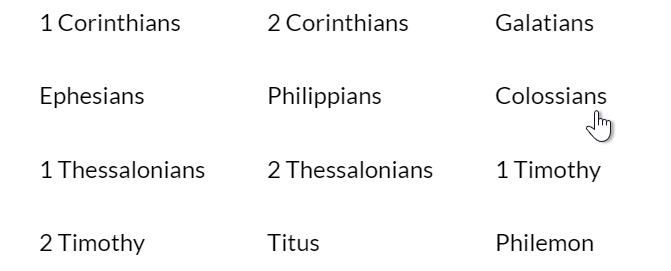

Whichever way of describing his undertaking is most accurate, what Simeon produced is a massive, multi-volume set of sermons spanning the canon of Scripture; the Horae Homileticae.1 They are expanded outlines, or “discourses in the form of skeletons,” intended to teach preachers to preach. And if you want to read some of them (let’s say I assigned 25 sermons on Colossians for a summer course, PDF here), you should bear in mind that these are not just sermons, but worked lessons in homiletical understanding of the Bible.

Here are a few methods and hints for reading a Simeon sermon profitably:

Simeon works hard on his opening paragraphs, but don’t start with them. Instead, look at the passage of Scripture (it’s printed on the page), then look at the sermon title. Ask yourself why Simeon chose the theme reflected in the title. Usually there are a half-dozen other themes he could have chosen: Colossians 1:21-23, for example, is about how we were alienated from God (there’s a theme!), but have now been reconciled (another one) in the body of his flesh through death (that’s 3) in order “to present you holy and unblameable and unreproveable in his sight” (a purpose clause, that’s 4) if you continue in the faith (5) not moved from “the hope of the gospel” (easily 6). But for his title of Sermon 2170, Simeon gives us “Sanctification the End of Redemption.” And the sermon focuses on that purpose clause: Christ saved us “so that” he could present us perfect.

In most cases, the move from the passage to the title is crucial for understanding what Simeon’s up to. He’s not a commentator, and he’s not a devotional writer. A commentator would cover everything. A devotional writer would select one thing to meditate on. But a preacher’s mind has to identify the key point that will capture the flow of thought, and provide the best opportunity for bringing the word of God to the people of God. In the case of Sermon 2170, Simeon knows he can preach sin, salvation, and sanctification all at once if he shows how sanctification is the purpose or goal.

Once you’ve considered the text and the theme, read his opening paragraph. He usually starts from a broad perspective, and says sententious things like (in this case) “OF all the subjects that can occupy the human mind, there is not one so great and glorious as that of redemption through the incarnation and death of God’s only-begotten Son.” Sometimes he glances at the current situation, or plays off of what his audience expects. Often the opening sentences are calls to lift up your thoughts to higher things. But they’re all worth considering and even imitating (though with pretty obvious adjustments needed for current sensibilities).

The next thing to look for in a Simeon sermon is the outline, usually marked by a clear set of Roman and Arabic numerals. In the case of Sermon 2170, the outline goes:

I. What the Lord Jesus Christ has done for us

1. Our state was awful in the extreme

2. But the Lord Jesus has interposed to deliver us from it

II. What was his ultimate design in doing it

III. What is necessary to be done on our part

1. It was by faith that we first obtained an interest in Christ

2. By the continued exercise of the same faith we must secure the harvest

The key point is roman numeral II, “his ultimate design.” But Simeon has a fine mind for analytically unfolding a point, showing its presuppositions and implications. Again, these outlines are the real skeletal elements of these sermon skeletons.

Under these outline points Simeon places exposition, printed in brackets. The brackets suggest that what he writes in these longer prose sections are only suggestive examples. This is what he would say if he were preaching it; this is how he would expand on the point. Though these paragraphs contain most of his best writing, you really can skip or skim them, with the live question of what you would say, or what you would need to hear, in an exposition of the passage.

Finally, Simeon often ends by suggesting application points that should be considered for various audiences, or sub-audiences within the congregation. In the sermon we’re looking at, he recommends that the preacher close by addressing: 1. the unsaved and 2. the saved. And he provides sample charges for what each type of listener needs.

A brief word on Simeon’s theology. He does in fact function with a definite biblical theology and even a systematic theology. You can spot his biblical theology in part by seeing what organizing schemas he constantly returns to: justification and sanctification; covenant; the works of the Trinity; etc. He also gives away his biblical theology in his obvious preference for larger and more comprehensive books, which he gives interpretive priority. For example, when he is preaching through Galatians (that short sharp shock against legalism) he constantly explains it in terms of Romans (that long, balanced, and comprehensive account of the meaning of the law in God’s plan). It’s actually amusing how often Simeon points out that what a hard phrase in Galatians actually means is Romans. Something similar happens in the Colossians sermons, where Simeon keeps up a constant running set of cross-references to Ephesians (a book on the same topic but half-again longer and more discursively structured).

Simeon also has a systematic theology informing his work, and it’s basically evangelical Anglicanism. So it’s decidedly Protestant, benignly Reformed, and well balanced between the great objective truths of revelation (Trinity, incarnation, atonement) and the spiritual experience of those who hold that faith. Without being wooden about it, Simeon does take his bearings from the 39 Articles. And while he doesn’t run a set of footnotes to the Articles or to the Elizabethan Homilies, Simeon does often use the phrase “as our church teaches,” and “our church” equals “the church of England.” Finally, though Simeon’s soteriology is characteristically Reformed, he is scrupulous about avoiding “addiction to system,” and refuses to bend or trim his interpretation of any given passage just to make it line up with his systematic theology more neatly.

___________________________________

1This is an unwelcoming title to us now, but perhaps in the early 19th century, when many resource books were called Horae, it suggested that the scholarly author had spent many “hours” at his task and was now giving out the fruits of that labor. All the volumes are scanned and online in various places (I recommend Internet Archive). The StudyLight site also has done a great job of displaying them canonically so you can click through to any passage of Scripture and get clean html text of Simeon on that passage.

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.