A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

Parable of the Land Surveyor

This is the eulogy I delivered for my stepfather-in-law, William Ralph Paris, on Sept 25, 2024 in western Kentucky. I should have spoken a little more about the presence of music in his life. The music at the memorial service included a traditional shape-note performance of “There is a Happy Land” and a congregational singing of “Higher Ground.” Both songs are appropriately land-related and old-fashioned.

Family, friends, loved ones, and neighbors,

We are gathered here today to remember the life, and to mourn the death, of William Ralph Paris, Jr.

It’s not exactly clear to me what I should call him, because he went by many names: William and Ralph, of course, but also Will, Rodney, Rodsey, Papa Will, Papa, and several more context-dependent names and nicknames. He also handed out nicknames for others: he always called me Sir Frederick Von Sanders, which is not my name. But you couldn’t really stop him once he got started.

William had a long life and was “full of years,” as the old saying goes. Here at this service we have a brief time together to consider his long life, and to say something about who he was and what he stood for.

Just a few weeks ago (about August the first) I had a conversation with William about this funeral service. I asked him what verse from the Bible was the most meaningful to him. He knew the Bible well, and he could have called up many passages. William had taught from Scripture regularly at Pleasant Hill Regular Baptist Church, and he regularly worked through the Sunday lesson material in Bible study. He had plenty of Bible on the tip of his tongue.

But he settled very easily on a passage that he promptly quoted from memory. It’s from the Old Testament book of Micah, chapter 6, verse 8:

8 He hath shown thee, O man, what is good;

and what doth the Lord require of thee,

but to do justly,

and to love mercy,

and to walk humbly

with thy God?

As he quoted this passage, William nodded decisively, looking straight at me and punctuating the words with that characteristic quick downward jerk of the chin, as if to say, “that about settles it,” or maybe, “everybody ought to agree with that, and if they don’t, too bad for them,” or maybe even, “so there.”

It really is a perfectly fitting text for William Ralph Paris. It starts with an appeal to what God has already made clear to everybody: “he already showed you what is good, man” and ends with the sharp barb of a rhetorical question, almost that Paris grin, interrogating us a bit sarcastically, after all, “what is it that the Lord requires of thee?” Well? What does the Lord require of thee?

But Micah 6:8 doesn’t leave the question hanging rhetorically; it also goes on to answer its own question: The Lord requires three things:

1. Do justly. 2. Love mercy. and 3. To walk humbly with thy God.

[1. Do Justly]

We should linger for a moment over that first requirement, “Do justly,” not just because William has drawn our attention to it by proposing it as the text for this service, but because there is something in the life of William Ralph Paris that serves to underline and illustrate the command, “do justly.” How so? Consider it a kind of parable; the parable of the land surveyor. The kingdom of heaven is in fact like a land surveyor who went forth the measure the fields.

Doing justly, that is, practicing justice, means recognizing that there are standards above us that govern how we ought to behave. There are rules, laws, principles, and categories within which we ought to live. You have to ascertain what those standards are before you can begin to align your life with them. To do justly is to know where the lines are and to dwell accordingly.

And the land surveyor is the one who discerns the invisible lines that invisibly carve up the territory that the rest of us just live on. Using all the tools and techniques of his trade, the land surveyor does not simply invent new lines, but traces out the inscrutable lines that run back and forth among us, along our roads and between our yards. “Do justly” means to rightly divide things where they are rightly to be divided. In English, “justice” has the synonym “righteous,” and just a few hundred years ago our ancestors pronounced “righteous” as “rightwisse,” or “right-wise.” Isn’t that a great word for justice? Right-wise. Not out of whack. Not cattywhompus, not skewed or wobbly, but square, straight, aligned, and in the zone. What does the Lord require of the surveyor but to do right-wise?

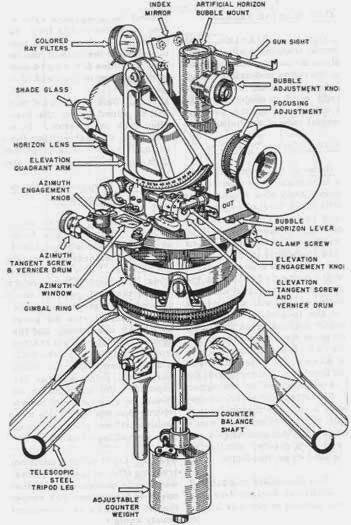

William worked for decades in the profession of surveying. He made use of levels, sights, scopes, trough compasses, plane tables, and that surveyor’s tripod, the mysterious and mathematical angle-measuring instrument called the theodolite.

He consulted old maps, listened to legends and tested their truth, studied forgotten documents stashed securely for decades in courthouse basements, and tried to pick the true names out of landmarks that had gone by several names. He stomped through fields seeking long gone trees, the mouths of wells covered over, the paths of creeks that had wandered away. The goal was to discern the old lines, to uncover the law, to establish the possibility of aligning with it, and of doing right-wise. He had an excellent education from Fredonia High School and Centre College, plus military discipline and state-of-the-art training from Purdue, but as the years went by he updated his education, learning to integrate computer-assisted design, aerial photography, and satellite-assisted GPS data in his quest for solid truth, truth you could do something with.

All his life, William learned things and knew things; he was an incessant fact-gatherer and thing-knower. It is amazing to think of how much he knew about local history. If you ever took a drive with him, you know that he could keep up a running commentary on everything he passed by: the trees, the slope of the land, the history of the houses, and the very composition of the soil! And it was all factually accurate, usually delivered while driving thirty-five miles per hour, making an alarming amount of eye contact, and grinning. Now that he has passed on, we all recognize what a gap he leaves. Who else knows what he knew? Just in the last few days here on our visit, my wife and I have had a half dozen questions about local landmarks that we’ve wanted to ask William about; now there’s nobody to ask.

All of this deep and particular knowledge gave him a kind of visionary quality; he saw things nobody else could see. Consider his farm and its historic restored house, Sweet Prospect. It developed through a slow growth toward the realization of his vision, a vision of what Sweet Prospect ought to be. When he began to preserve and restore the property, he seemed to be guided by a clear and steady perception of where the walls and walkways would be. As the building gradually took shape, his family and friends could also begin to see what he saw.

His college fraternity was Beta Theta Pi, a brotherhood united under the motto “Men of Principle.” Certainly William was a man of principle. It was the invisible principles always before him that guided the growth of his projects as they became real, emerged into the world, and became right-wise.

So do justly. Build square. Align your life with clear principles. We should all consider the parable of the land surveyor.

[2. Love Mercy:]

But William’s favorite Bible verse tells us more than “do justly.” Beyond telling us what to do, it tells us what to love: Love mercy. That’s good: Micah knows that life is more than just doing, but also loving. Do justice; Love mercy.

Williams life was not just a matter of hard working hands, but of a big heart. He was devoted to his family, and collected friends as he went about his business. He loved music, cultivated it, and shared it with his community. He was known for what he loved, as much as for what he did.

But “love mercy” is also a good addition to “do justly” because none of us “do justly” with the consistency that justice itself requires. None of us discern all the right lines or behave consistently with them; not all of us even get the right principles and not one of us measures up to our own principles. And once again, the land surveyor knows this. William himself knew he did not live up perfectly to his own standards across the whole course of his life. He knew that he needed to love mercy, so he could give it and receive it. His life as a surveyor reminds us of doing justly because it is a parable about being rightwise, not some perfect performance of it.

From another perspective, land surveyors spend most of their time not with the perfect lines of transcendental trigonometric measurements, but with the crooked and wobbly things of this earth.

What is land surveying but trying to draw straight lines on a curved planet, grids on globes, and fixed boundaries in unstable real estate? It’s enough to break your heart, thinking about the struggle of fixing those solid lines onto an unsolid world. Recently William described to me how “north” has three different meanings that never perfectly align: geographic north, stellar north, and magnetic north. There are variations among them, and aligning them is no easy task.

William had high standards: to do justly. But in applying them he needed grace: to love mercy.

Remember, our text is from Micah. and Micah is a book of the Bible, and we should all know that the Bible is not just about the law that says “do justly,” but also the gospel that tells us God himself loves mercy, and is ready to forgive anybody who confesses their sin and trusts the God of mercy with the rest of their life.

We all need forgiveness. William learned to love mercy, to be a man of principle who could allow for deviations and failures by himself and others, who could accept people for what they were, and to live in a community of mutual forgiveness. He needed forgiveness for his sins from God, and he needed forgiveness from his family when he inevitably failed to be all that he should have been to every one of us at all times. We bury a human here, and this is what our life is. What the Lord requires of us is to do justice and to love mercy.

[3. Walk Humbly]

And this brings us back to Micah 6:8. If you do justly and love mercy in this way, you will take the third step, and “walk humbly with your God.” Humility means knowing your place, recognizing that God is great and that you are small; that he is in heaven and you are on the earth; that God inhabits eternity and that you are a creature who should know its place.

William knew his place. It was Fredonia. How he loved it! He returned to it, nurtured it, cultivated it, and sang its praises. The people in this room are a testimony to all the groups he joined and civic connections he cultivated. He was a joiner and a public man, but ultimately what he loved was the land itself.

Another great passage, close to our text, is Micah 4:4, “they shall sit every man under his vine and under his fig tree.” Here is its context:

“Come, let us go up to the mountain of the Lord… that he may teach us his ways and that we may walk in his paths… They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks, neither shall they learn war anymore; but they shall sit every man under his vine and under his fig tree, and no one shall make them afraid, for the mouth of the Lord of hosts has spoken.”

This biblical image of simple contentment, a vision of peace and prosperity, is grand and glorious precisely because it is little and local. George Washington loved this image from Micah, and quoted it from memory in his letters. After a busy life, he aspired to sit under his own vine and fig tree, in his own place, among his own people. This was a noble ambition for a man who understood “what is good,” and what the Lord requires of us all: To do justly, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with our God.

[closing prayer]

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.