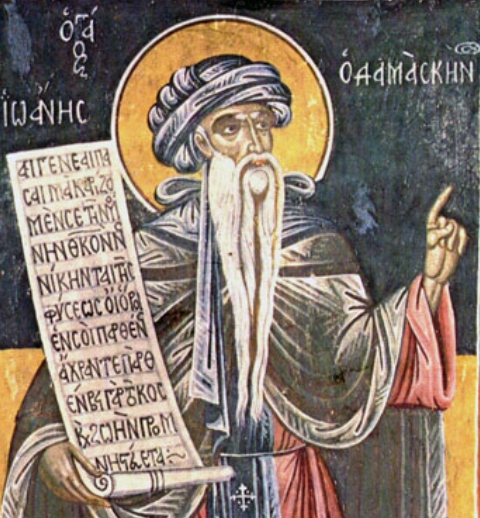

A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

Two Kinds of Own-Making in Christology

“The Word became flesh,” and “he became a curse for us.” These two claims, from John 1:14 and Galatians 3:13 respectively, use the same verb (became) to explain how Jesus brought about redemption. But surely Jesus didn’t “become flesh” and “become a curse” in the same way. To become flesh is to take human nature into personal union, to assume human nature for salvation, for its healing and renewal. But to become a curse is not to take a curse into personal union for its healing and renewal; it makes no sense to talk about saving a curse.

John of Damascus has a helpful explanation of how to distinguish these two things. He does it by noting the difference between two kinds of “appropriations” in Christology. The Son appropriates human things, making them his own, in two distinct ways. Here is John’s whole treatment of it:

One should know that there are two appropriations. One is natural and substantial, the other is personal and relational.

The natural and substantial appropriation is is that by which the Lord out of his love for humanity assumed our nature and all the natural characteristics that belong to it, by nature and in truth becoming a human being and experiencing the natural characteristics that pertain to humanity.

The personal appropriation occurs when someone takes on the character of someone else through a relationship, I mean a relationship of pity or love, and in his place says things on his behalf which do not in any way belong to him personally. It is in this sense that Christ appropriated our curse and abandonment and such things that are not part of our nature, not because he himself was these things or became them, but because he took our character upon himself and set himself alongside us. And his becoming a curse for us belongs to this category.1

It’s worth considering the fact that both kinds of action really can be discussed under the same heading, in the same chapter:2 both are instances of the Son of God saving us by making our stuff his own, or owning it. The Greek word John uses is οίκειώσεις, oikeioseis.3 It’s a word with a lot of ancient philosophical resonance, especially in Stoicism, but the basic meaning can be seen by noting that it’s a verb form of the noun in that crucial opening syllable, oik: home. To oik– something is to assimilate it, or affiliate it, or appropriate it into your own domain. Or maybe for you to come to be at home in it? I’m not quite sure. But in the context of a dynamic movement, it suggests two steps: first something isn’t your own, and then you make it your own. It’s not properly your proper property, but you ap-prop-riate it. That’s how Jesus saves.

But then it’s worth considering this distinction: there’s own-making and then there’s own-making. The Word becomes flesh: He “assumed our nature and all the natural characteristics that belong to it…experiencing the natural characteristics that pertain to humanity.” But the holy one became a curse: he made common cause with the accursed and “in his place says things on his behalf which do not in any way belong to him personally.” This is the sense in which the Son “became” those bad things that do not belong to human nature, things that destroy human nature.

The distinction between two kinds of own-making is a helpful analytic move that will let us think and speak clearly. But it’s also a distinction that cuts deeper than any two-edged sword: It shows that God our Savior knew how to make a distinction and separation between us and our sin. He made that distinction and made both his own: one he appropriated to save and restore, the other he appropriated to do away with and destroy.

__________________________

1John of Damascus, On the Orthodox Faith: A New Translation of An Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, Introduction, Translation, and Notes by Norman Russell (Yonkers, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2022), 224. This is the entirety of chapter 69, “On Appropriation.” I have broken it into three sections. Also, the final sentence in my quotation (“And his becoming a curse…”) is only included in some manuscripts, so Russell demotes it to a footnote. No doubt he is right to do this, but I wanted the extra text because even if it is later commentary, it helps emphasize the point I am making.

2Did you know “chapter” is directly derived from the idea of headship? Think about it in any romance language, or several others: capitulum, chapitre, capital, capitulo, kapitel, cephalaio.

3There are several helpful key terms in the Greek text (which the SVS edition prints on left pages). For instance, it is instructive to see that “personal and relational” is prosopike kai schetike, as contrasted with “natural and substantial,” phusike kai ousiodes. Here is the full text of chapter 69 from the Kotter edition (I’ve just cut and pasted it w/out proofreading):

Χρή είδέναι, ώς δύο οίκειώσεις* μία φυσική καΐ ούσιώδης, και μία προσωπική και σχετική. Φυσική μέν ούν καΐ ουσιώδης, καθ’ ήν δια φιλανθρωπίαν ό κύριος τήν τε φύσιν ήμών και τά φυσικά πάντα άνέλαβε φύσει και άληθεία γενόμενος άνθρωπος καΐ τών φυσικών έν πείρςι γενόμενος· προσωπική δέ, ότε τις τό έτέρου ύποδύεται πρόσωπον διά σχέσιν, οίκτόν φημι ή αγάπη ν, και άντ’ αύτού τούς ύπέρ αύτού ποιείται λόγους μηδέν αύτώ προσήκοντος, καθ’ ην τήν τε κατάραν και τήν έγκατάλειψιν ήμών και τά τοιαύτα ούκ όντα φυσικά, ουκ αυτός ταύτα ών ή γενόμενος οίκειώσατο, άλλά τό ήμέτερον άναδεχόμενος πρόσωπον καΐ μεθ’ ήμών τασσόμενος.

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.