A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

Christ for Us, and the Holy Spirit in Us (Bonar’s Kelso Tracts)

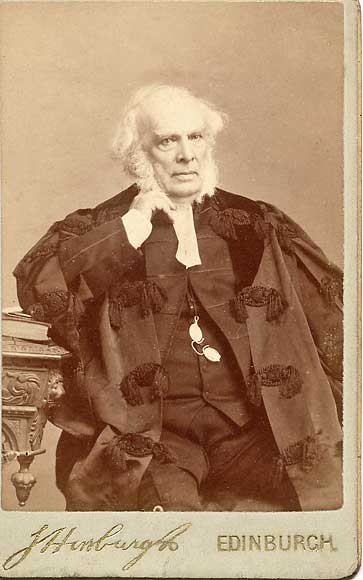

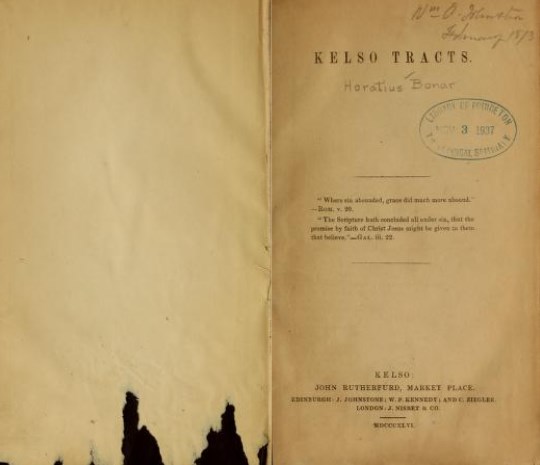

While pastoring in Kelso, Scotland in the 1840s, Horatius Bonar [1808-1889] occasionally published little pamphlets, between three and twelve pages long, just to reach his local audience. Though he initially intended them only as written “helps to his own pastoral work,” without “any ambitious aim of writing for a wider circle,” they proved popular beyond his own congregation. He gathered 37 of these and published them under the title of Kelso Tracts; in this form they became a minor evangelical masterpiece of spiritual theology. The bound volume runs to about 300 pages, but its original editions didn’t have continuous page numbering: the page count started over with each tract, reinforcing their origin as individual booklets. A few of the tracts are actually republications of older authors (Becon, Baxter, Whitefield1) in a form Bonar could easily distribute.

Such an assemblage of tracts is bound to range over a lot of different subjects, and their thematic unity is predictably as broad as a survey of the things Bonar found it necessary to preach and teach during his ministry in Kelso. But Bonar had a well-organized mind and a definite focus as an evangelical pastor. As a result, in the preface he is able to summarize the “leading object” of his work:

The leading object of the whole Series may be said to be, to endeavour to bring out with some fulness, perhaps with some repetition, the Work of Christ, and the Work of the Holy Spirit, in reference to the wants of sinners.

If I can paraphrase that a bit, I’d say Bonar’s idea of effective gospel ministry is carefully structured by an applied, evangelical Trinitarianism. In particular, the Kelso Tracts show his concern to take in the comprehensive character of the Christian life by way of a careful distinction between the work of the Son and the work of the Holy Spirit.

It was found, in conversation with the troubled and doubting, that much confusion prevailed in their minds, as to both of these points, the Work of Christ, and the Work of the Spirit. There seemed a continual tendency to intermingle these two things, and so to subvert both; to build for eternity, partly on the one, and partly on the other, and so to come short of any true and sure establishment of the soul in grace. Many seemed most perversely bent on taking these two works as if they were one compounded work, trying to build their peace, their forgiveness, their salvation, upon a mysterious mixture of the two. The external and the internal were not kept distinct; the objective and the subjective were confusedly tangled together, so that neither was understood aright, and both were misapplied. It was not CHRIST FOR US, AND THE HOLY SPIRIT IN US, but it was Christ and the Holy Spirit together, both for us and in us. Thus, all was vagueness and indistinctness in reference to what Christ had done, and in reference to what the Holy Spirit had been sent down to do. Hence, all was darkness in the soul. There was no peace, for the ground of peace was not rightly seen; there was no holiness, for the source of holiness was but imperfectly apprehended. This Popish mixture of these two things —”Christ for us, and the Spirit in us,” required to be exposed to view, its unscripturalness condemned, and its evil influence neutralized.

It is CHRIST FOR US, that is our peace. It is THE HOLY SPIRIT IN US, that is our regeneration and holiness. Woe be to the soul that intermingles these two, and seeks to rest his peace and hope, partly on what Christ had done for him, and partly on what the Spirit is doing in him. (vi; there follows in a footnote a long quotation from John Owen on the same subject.)

Bonar explains a bit more:

It is only, then, by setting distinctly forth the Work of Christ for us, and the Work of the Spirit in us, that we can really present the sinner with what he needs. As absolutely helpless and unholy, he needs an Almighty Spirit to new-create him. As condemned and accursed, he needs a Divine substitute and peace-maker. And in making known the latter, we preach the Gospel. For the Gospel is the good news of what another has done for us….

And in setting forth the work of the Spirit, we are called upon to be careful, on the one hand, to show the necessity for the direct and special operation of His power; and on the other, to guard the sinner against resting upon the Spirit’s work, as if it were part of the foundation on which he builds for heaven. The work in us, however deep and decisive, can never pacify our consciences or reconcile us to God. It can never make, or maintain, our peace. It cannot be our resting place, or our Saviour.

Bonar thinks of this ordered reciprocity of the Son and the Spirit as the structure that enables us to speak meaningfully of all that is in salvation; it is in some sense the “tangible shape” of the message in its integrity:

It is of the utmost moment that these things be attended to, otherwise we shall never present the Gospel in any really tangible shape. Nay, we shall so confound things that differ, that they to whom it is preached shall not be able to see in it any glad tidings at all. With much that is evangelical, both in phrase and sentiment, in our statements, we may yet miss the real point and burden of the Gospel, and so leave men nearly as much in the dark as if we had set them upon providing a righteousness for themselves.

I find his structural observations especially significant. Without the Trinitarian background operating at least subliminally for the teacher, pastoral speech can turn into a shambles, with bits and pieces of gospel truth jostling around but never hanging together. It’s Christian word salad; formless static made up of fragments of truth; tohubwabohu with Bible phrases floating around in it.

To take the renewing work of the indwelling Spirit as the basis of salvation is “an entire inversion of God’s order.” The only way to embrace the work of the Son and the Spirit is to observe the distinction and correlation between them. Premature harmonization of the two is really just pervasive confusion of the two. The result is a sophisticated form of seeking justification by works; “It ends with securing forgiveness, whereas God’s religion begins with securing it.”

______________________________________

1Tract 2, “The Faithful Saying,” is by Thomas Becon (1510-1567); Tract 4, “Jehovah Our Righteousness,” is by George Whitefield; Tract 10, “Now,” is by J. M’Donald of Calcutta; and Tract 11, “To the Unconverted,” is by Richard Baxter.

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.