A scene from The Canterbury Psalter (12th century)

Blog

What’s Common, What’s Proper (Basil)

There’s a passage in Basil of Caesarea’s Against Eunomius (written 364) that is so helpful that I keep coming back to it over and over. I think I had to see it quoted about a dozen times before I finally began to recognize just how good it is. It may not jump out and grab you instantly. But if you’re trying to think about the absolutely fundamental principles of trinitarian theology, Basil makes a few moves in this passage that draw everything together.

I was about to make a handout of the passage for students, when I realized it would be better to put it here in public.

So here it is. It’s got everything: conceptual clarity, terminological precision, and epistemic distinctions that help keep you on track. I’ll add a little commentary below, but the main thing to see here is primary text that everybody needs to have on hand (or on blog, as it were).

| The distinctive features, which are like certain characters and forms observed in the substance, differentiate what is common by means of the distinguishing characters and do not sunder the substance’s sameness in nature. | Αἱ γάρ τοι ἰδιότητες, οἱονεὶ χαρακτῆρές τινες καὶ μορφαὶ ἐπιθεωρούμεναι τῇ οὐσίᾳ, διαιροῦσι μὲν τὸ κοινὸν τοῖς ἰδιάζουσι χαρακτῆρσι· τὸ δὲ ὁμοφυὲς τῆς οὐσίας οὐ διακόπτουσιν. |

| For example, the divinity is common, whereas fatherhood and sonship are distinguishing marks: from the combination of both, that is, of the common and the unique, we arrive at comprehension of the truth. | Οἷον, κοινὴ μὲν ἡ θεότης, ἰδιώματα δέ τινα πατρότης καὶ υἱότης· ἐκ δὲ τῆς ἑκατέρου συμπλοκῆς, τοῦ τε κοινοῦ καὶ τοῦ ἰδίου, ἡ κατάληψις ἡμῖν τῆς ἀληθείας ἐγγίνεται· |

| Consequently, upon hearing ‘unbegotten light’ we think of the Father, whereas upon hearing ‘begotten light’ we receive the notion of the Son. | ὥστε, ἀγέννητον μὲν φῶς ἀκούσαντας, τὸν Πατέρα νοεῖν, γεννητὸν δὲ φῶς, τὴν τοῦ Υἱοῦ λαμβάνειν ἔννοιαν· |

| Insofar as they are light and light, no contrariety exists between them, whereas insofar as they are begotten and unbegotten, one observes the opposition between them. | καθὸ μὲν φῶς καὶ φῶς, οὐδεμιᾶς ἐν αὐτοῖς ἐναντιότητος ὑπαρχούσης, καθὸ δὲ γεννητὸν καὶ ἀγέννητον, ἐπιθεωρουμένης τῆς ἀντιθέσεως. |

| [p. 175] It is the nature of the distinguishing marks to show otherness in the identity of the substance. | Αὕτη γὰρ τῶν ἰδιωμάτων ἡ φύσις, ἐν τῇ τῆς οὐσίας ταυτότητι δεικνύναι τὴν ἑτερότητα· |

| And as for the distinguishing marks themselves, while they are often contradistinguished from one another such that they are separated to the point of being contraries, they certainly do not rupture the unity of the substance, as with the winged and the footed, the aquatic and the terrestrial, and the rational and the irrational. | καὶ αὐτὰ μὲν πρὸς ἄλληλα ἀντιδιαιρούμενα πολλάκις τὰ ἰδιώματα, πρὸς τὸ ἐναντίον διίστασθαι, τήν γε μὲν ἑνότητα τῆς οὐσίας μὴ διασπᾶν· ὡς τὸ πτηνὸν καὶ τὸ πε- ζὸν, καὶ τὸ ἔνυδρον καὶ τὸ χερσαῖον, καὶ τὸ λογικὸν καὶ τὸ ἄλογον. |

| Since there is one substance that underlies all of them, these distinguishing marks do not make the substance foreign to itself, nor are they persuaded to join each other in a kind of rebellion. They implant the activity of the things they identify as a kind of light in our soul, and guide to an understanding attainable by our minds. | Μιᾶς γὰρ οὐσίας τοῖς πᾶσιν ὑποκειμένης, τὰ ἰδιώματα ταῦτα οὐκ ἀλλοτριοῖ τὴν οὐσίαν, οὐδὲ οἱονεὶ συστασιάζειν ἑαυτοῖς ἀναπείθει· τῇ ἐνεργείᾳ δὲ τῶν γνωρισμάτων, ὥσπερ τι φῶς ταῖς ψυχαῖς ἡμῶν ἐντιθέντα, πρὸς τὴν ἐφικτὴν ταῖς διανοίαις σύνεσιν ὁδηγεῖ. |

| Basil of Caesarea, Against Eunomius, Translated by Mark DelCogliano and Andrew Radde-Gallwitz. Catholic University of America Press, 2011. Book 2, section 28. Pages 174-175. | Basile de Césarée: Contre Eunome suivi de Eunome Apologie, Bernard Sesboüé, Georges-Matthieu de Durand, and Louis Doutreleau, Sources Chretiennes 305 (Paris: Cerf, 1982-1983), 2:28; 120. (But this blog text is inserted from Thesaurus Linguae Graecae (TLG)) |

A few remarks about why this is such a helpful passage:

I admit it doesn’t look all that promising at first. It’s plucked from a book-length argument, every phase of which is entangled in the presuppositions of Basil’s opponent. That opponent, Eunomius, is a rationalistic debater committed to idiosyncratic views. But at certain points, Eunomius’ dogged peculiarity roused Basil to be clear and explicit about certain points that simply wouldn’t have emerged so definitely a few decades previously, in the days of a simpler and more naïve Arianism. So in this indirect way, we can be grateful that Eunomianism provoked this particular orthodox reaction.

A lot of teachers try to summarize trinitarian theology by talking about the one and the three. That’s fine; it follows the cadence of the later Athanasian Creed. But Basil works at another conceptual level, directing our attention to what is common to the divine persons and what is proper to them. The Greek words can be helpful here because they’re concise and they sound more technical in Greek: there are “distinctive features” (idiotētes) that mark out the persons from each other. Notice that in paraphrasing this, I have to keep saying “persons,” but a strength of Basil’s way of talking is that he has not yet introduced that term to distract us. Focus instead, first, on the common and the proper. That will get you the persons.

The common” (koinē) is divinity; the distinct or proper-to-a-person (idiōmata) are fatherhood and sonship. Notice that Basil’s working with three abstract nouns: theotēs, patrotēs, huiotēs. There’s a godness that’s common to Father and Son, but fatherness is particular to the Father, while son-ness is proper to the Son.

It’s in combining the two ways of talking (common and proper) that you assemble in your mind a truth about God that has both elements. You “arrive at comprehension of the truth” by gathering up what is common to Father and Son along with what is proper/unique/distinct.

The result is the wonderful theological phrase “God the Father,” which combines the common and the proper, godness and fatherness, to pick out the one person. “God the Son” does likewise. But here Basil doesn’t go directly for those phrases (see his Letter 236 for that); instead he teases apart the Nicene phrase “light from light.” When we say Light from Light, we indicate unbegotten light and begotten light, one light. They are light and light, no “contrareity.” But they are begotten and unbegotten, in which we perceive an opposition or “antithesis” (epitheōroumenēs tēs antitheseōs) between them.

“Distinction” is probably the safest word to use consistently here, because opposition and antithesis connote conflict. And the whole point is that they “do not rupture the unity of the substance,” but instead the whole point of these idiōmatōn is that they “show otherness in the identity of the substance.” Terms like Father and Son are “contradistinguished…to the point of being contraries,” but they’re not the kind of opposites that make them different kinds of things (like aquatic and terrestrial are). Terms like Father and Son, or unbegotten and begotten, are instead paired contraries within a single substance rather than markers of divergent substances. Because, remember, godness is common to them.

Finally, Basil concludes with some interesting remarks on epistemology, or on the way these terms function in our minds to bring about understanding: When we hear them, “they implant the activity of the things they identify” into our minds, so that those energēia work as a kind of light in our soul, incomprehensible realities guiding us to something we can understand. Two things worth remarking on here: first, this conclusion about light in our soul matches the fact that Basil has been talking about light from light. And second, only a close fight with a rationalist like Eunomius would have forced Basil to make a nuanced statement about the way in which Christians have true knowledge of the incomprehensible Trinity.

Finally, there’s what you might call a sort of Thomist-friendly version of this passage going around these days. That makes sense, because this Cappadocian refinement of trinitarian theology is the common stock of the Christian faith, and Aquinas cultivated it well. At numerous points in the text, it’s tempting to elaborate it a bit further with reference to relations of opposition and notional acts. One of the fountainheads of the Thomist unpacking of the passage can be found in Gilles Emery, The Trinitarian Theology of St. Thomas Aquinas (Oxford University Press, 2010), 44-48, at 45. Here’s how his translation (or rather our English translation of his French translation) runs:

The divinity is common, but the paternity and the filiation are properties (ἰδιωμάτα); and combining the two elements, the common (κοινόν) and the proper (ἴδιον), brings about in us the comprehension of the truth. Thus, when we want to speak of an unbegotten light, we think of the Father, and when we want to speak of a begotten light, we conceive the notion of the Son. As light and light, there is no opposition between them, but as begotten and unbegotten, one considers them under the aspect of their opposition (ἀντίθεσις). The properties (ἰδιωμάτα) effectively have the character of showing the alterity within the identity of substance (οὐσία). The properties are distinguished from one another by opposing themselves, […] but they do not divide the unity of the substance.

See also Emery’s discussion there with its footnotes to contemporary French Catholic patristic scholarship. It’s wonderfully helpful to have Emery’s type of Thomism make its debts to Cappadocian theology conspicuous. These links were not being made evident enough 25 years ago, and as a result lots of people got away with exaggerating the East-West differences.

_______________________________

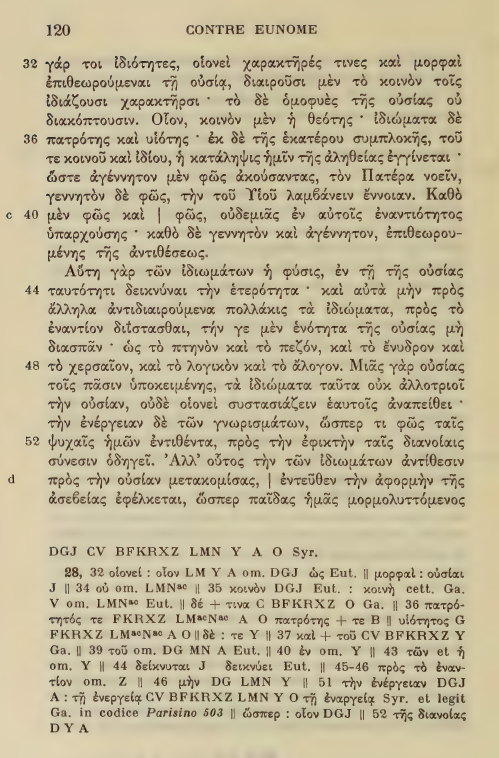

Bonus: In case you need to footnote this text, you might prefer seeing the SC version with your own eyes. (“I saw it on this guy’s blog” looks bad in footnotes.) So here’s a page shot of the text from the copy borrowable via the Internet Archive. Please note that exactly one word (the sentence-starting Αἱ) is on the previous page, 118; the rest is all here on 120. Alternating pages are the French translation.

About This Blog

Fred Sanders is a theologian who tried to specialize in the doctrine of the Trinity, but found that everything in Christian life and thought is connected to the triune God.